Blogs

Making of a Museum: the Collections Team, the Gatekeepers of Art

Khushi Bansal

The fifth article in our original series explores the central role of the Collections team in holistically looking after artworks housed in the museum.

Samuel Adoquei, a Ghananian author, quoted, “for centuries, the sanctuary of a unique art collection has been the secret beacon of endurance for important legacies. For any legacy to endure, it must provide timeless beauty and continuous inspiration for future imaginations. For these reasons, today’s art collector must know that timeless art comes from life and nature. Art founded upon the love of nature and tradition” (Adoquei, n.d.). The collections team at the Museum of Art & Photography handles a vast collection of artworks that is divided into six categories namely, Popular Culture, Photography, Modern and Contemporary Art, Living Traditions, Pre-Modern Art and Textile, Craft and Design. These works of art stand as a testament to the past, honour the present, and provide an insight into the future.

Split into three sub-divisions, the collections team consists of a registrar, archivists, and a photography team. The collections team at MAP is headed by Madhura Wairkar (whom we have previously spoken with, read her interview here). Rucha Vibhute and Prachi Gupta (whom we also interviewed, which you can access here) work as senior archivists, handling the Popular Culture and Photography departments at MAP respectively. Rucha comes from a background in art history. Patricia Trinidade works as an archivist, heading the Modern and Contemporary art department. Her expertise lies in Indian culture, history, and museology. Priya Lewis is an archivist splitting her time between the Textile and Photography departments. Her speciality lies in ancient Indian culture, archaeology, history, and museum studies.

Priya Latha is our registrar and has worked at MAP the longest! Although she started her career with no formal art education, over time she has acquired a certification in museum studies and gained a depth of practical experience. Currently, the photography department consists of two individuals – Shreya Chitre and Himani Bajaj. Shreya works as the studio manager with a background in photography, DSLR filmmaking, fashion, and advertising. Himani works as an assistant photographer with formal education in journalism, psychology, and literature. The team is diverse as they bring together their practical and academic knowledge to care for the collection at the museum.

Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur by Vivienne London, c. 1945, Silver gelatin print, PHY.01717

The journey of an artwork from the time it gets acquired by a museum is long drawn. Paperwork, documentation, and photography surround it as the team works on integrating it into the collection. To this, Priya Lewis said, “when an artwork is either donated or acquired, the first role is played by the registrar acknowledging that the object has been received and recording the incoming object by giving it an acquisition number. The next step would be to catalogue and photograph it based on whichever category it is in. At MAP we use Cumulus, a collections management system built internally by the tech team. We assign accession numbers, measure the work for storage and display purposes, and add descriptions that include contextual information as well as physical attributes. Additionally, we need to define culture and provenance, which translates to where it is created and how we acquired it. Once we catalogue, we figure out an ideal storage space for the object and make sure that the space is appropriate, in terms of humidity, temperature, and making sure it is kept away from pests, etc. Another important process is handling: we make sure we wash hands thoroughly and wear nitrile gloves wherever necessary (differs from case to case).”

In terms of photography, Himani started by saying, “the first thing is checking with the archivists the location and priority of the work. We then take the artwork and use appropriate resources. Handling the work is very central to what we do. We photograph them and make sure that we stick to what it looks like to the naked eye by using proper lighting and editing tools.” Shreya continued to add, “there is a fair share of trial and error in that process too. Even lighting is subjective. We must standardise it using tools like a colour checker to ensure that if any of the artworks need to be reproduced, they are as close to the original as possible. We have managed to set up a system to make sure that everything is standardised. Himani has taken the role of ensuring that they handle photography and I help with photographs that require editing in terms of retouching or colour correction.”

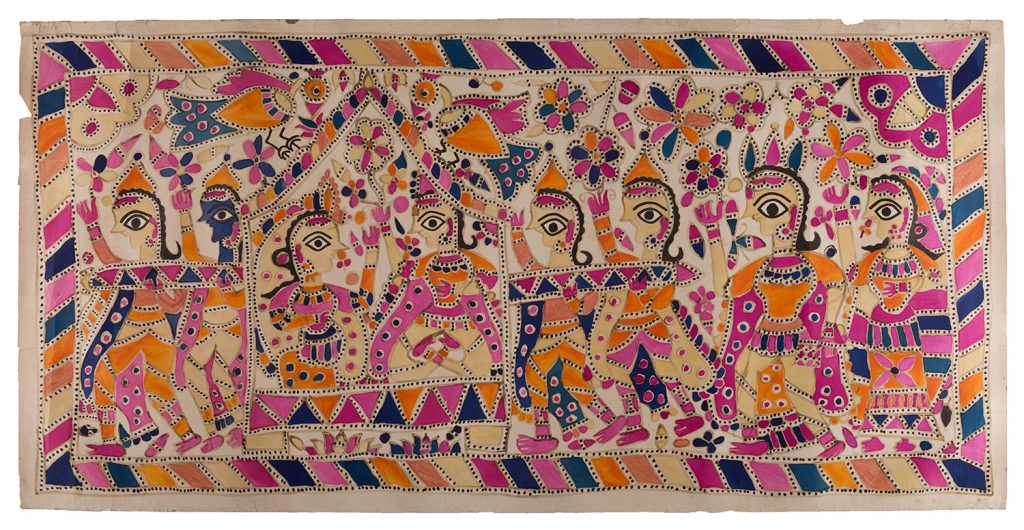

Doli Kahar (The Palanquin) by Leela Devi, 1978, Natural pigments on handmade paper, PTG.01958

Apart from acquiring, cataloguing, and photographing artworks, the collections team is helmed with several other responsibilities as well. To this, Rucha said, “apart from creating a database for objects, we also look at other aspects, such as establishing provenance and registering antiquities with the Archeological Survey of India (ASI). One of our key roles at the moment is to digitise the MAP collection, making it accessible to a larger audience.” As explored extensively in our previous interview with Madhura, collections care is central to the role of the team, preventative measures are taken in comparison to interventive ones. To summarise, the collections team looks after an object holistically from the time it physically arrives to storing it, cataloguing, and researching it. In turn, it enables other departments to do their work. There is no museum without a collection: what would you show in the museum then? The first interaction with the object happens with collections and it goes out into the world through the team, whether it is for an exhibition, public programme, or an educational workshop.

Human beings are inherently known to form opinions and perspectives – it is only natural. Yet, the collection has to be depicted from an unbiased perspective which enables people to create their own. To this, Patricia said, “it is not easy to always stay unbiased as some artworks were meant to convey specific ideas and emotions. If the artist has depicted something or labelled certain works, we cannot portray those in a different light. In most cases we do not provide descriptive explanations of artworks which then helps the viewers to form their judgement about the artworks.” Rucha added, “doing research also aids in maintaining objectivity. Every object that is part of our collection, be it a popular print or a sculpture, is thoroughly researched. We are able to establish context as we rely on facts.”

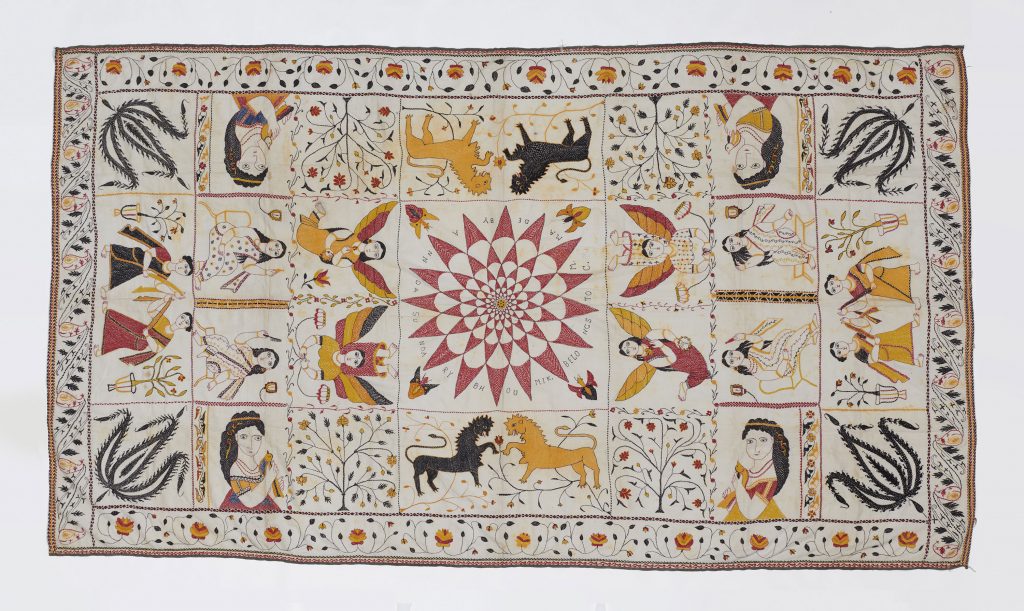

Two women making a garland by an Unknown maker, late 19th-early 20th century, Chromolithograph,

Shreya continued to say, “over the last few months, I have been working on the exhibition pamphlet for the permanent show at the physical museum. There has been so much back and forth on what otherwise would seem like non-issues. Every detail in every artwork we have photographed is being scrutinised by at least 10-15 people, from the publication designer to the exhibitions team, to Abhishek and Kamini. Everyone has a very unique perspective which sometimes I may miss as I view the artwork literally. In the case of 3D objects, there is a lot of conversation about what angle perhaps would best depict an artwork. This may seem to be a very nonchalant issue because you can take a front-angle image and that should ideally do it. That being said, I have had so many conversations with curators where they say “no, this brings out a perspective in a better way.” Therefore, it is a conversation between both teams and there is a standardisation where the viewer is not taken aback when they see a physical work; there are parameters that exist for it. Lighting changes artworks – what we can best do, as photographers, is make sure that we document what the artwork looks like in natural light, under the naked eye.”

Since the collection at MAP is divided into six distinct categories, I always wondered what perhaps the connectivities or interlays are between each of these. To this, Patricia said, “I think all the categories have certain similarities in terms of the themes or ideas they depict. Many artists are inspired or act upon the environment they come from or the one they currently inhabit. They draw ideas from their perception of the socio-political conditions in the country. The only difference is the medium or method through which their ideas find shape. Some choose photographs while others paint. Some were made a hundred years ago while others continue to be made.”

Being a member of this team myself, it is a privilege working with physical works of art almost on a daily basis. Holding an artwork between your fingers is an unexplainable feeling – you are holding an idea, identity, memory, or a piece of the past (or present). The point being that a collection brings to life histories, identities, and represents communities through ideas such as mediums, race, gender, colonialism and cultural practices amongst other things. Therefore, a collection encompasses all things related to our society providing a deep insight into the functioning of the human mind.

A favourite question in this interview series has been, “what is your favourite artwork in our collection?” Honestly speaking, I was a little terrified to ask this question to the team and the only reason for this is because we handle these works very intimately and perhaps interact with them very differently. Therefore, a running sentiment the whole team agreed with was that no one has a favourite. Instead, all the artworks are treated equally and it may be because of the way we view them. These works come to us regularly and the type of engagement we have with them is different. We appreciate the artworks but do not necessarily view them the same way as others do. As a result, we either have hundreds of favourites, or none at all.

A recent graduate from Central Saint Martins, London, Khushi Bansal is an aspiring curator with a keen interest in baking a perfect loaf of bread. She is an Archivist in MAP’s Collection team.

References

1. Adoquei, Samuel. n.d. “Collectors – Sam Adoquei Sam Adoquei.” Sam Adoquei. Accessed September 20, 2022. http://www.samadoquei.com/collectors/.