Blogs

How Blue is Blue?

Dhruvika Bisht

MAP’s Conservator – Restorer, Dhruvika Bisht, explores the beauty and uses of the colour indigo in paintings and describes the techniques through which it is revealed the aesthetic value of this omnipresent pigment.

***

If there is a colour that perfectly portrays the sensory dialogue of lightness and depth, it is the colour Blue. A colour so abundantly around us yet so rare in nature that a human response had to be devised to mimic the ocean under a night sky and finds a profound reference in all human civilisations across history.

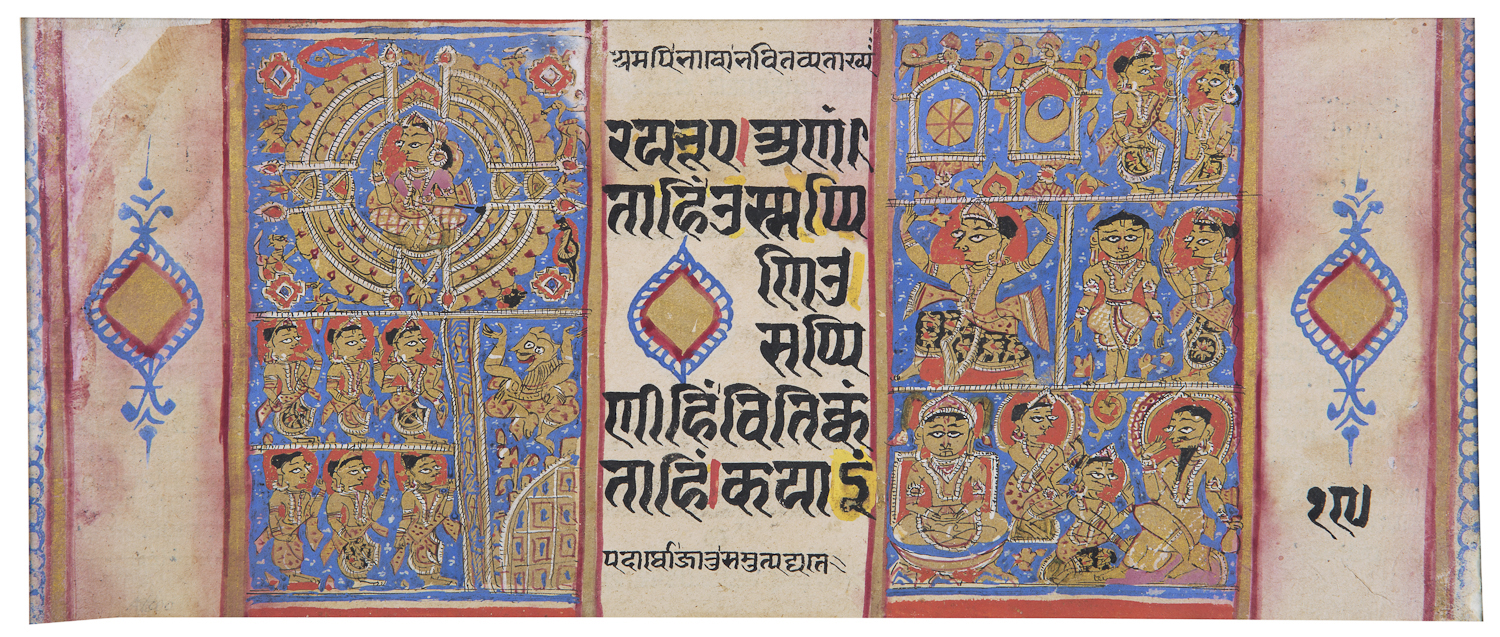

Before the advent of synthetic substitutes, no blue represented a more accurate human response to the colour, than indigo. For about six millennia, indigo remained the only blue pigment derived from natural sources. Earliest records for indigo usage can be traced to the cuneiform from 600-500 BCE, Babylon, acquired by the British Museum in 1892. The small tablet when deciphered in the 1990s showed the instruction to ‘dye wool blue’; suggestive of indigo dyeing process. Several indigo plant varieties and even mollusc shells were used to extract the blue colourant. Extraction of indigo and its derivative dye groups is historically linked to Mediterranean and Middle Eastern civilisations. Archaeological finds of mollusc pigment extraction sights in the Mediterranean and Persian Gulf suggest the usage of indigo pigment between 1800 and 1600 BCE. One of the oldest examples of indigo dyeing from the plant Indigofera in the Indian subcontinent is linked to the Harappan Civilisation (3300-1300 BCE). Since the discovery of extracting dyestuff from the plant was made independently in different parts of the world at different times. Several traditional methods were therefore known in most cultures, especially those under the chokehold of European imperialism.

On the other hand, the most common indigo bearing plants, Indigofera tinctoria, finds its etymological roots in the Greek word indikon, implying “substance from India.” In fact, the earliest record of the dye’s usage in the western world, under the name indigo, is attributed to Pliny. During the Roman empire, the use of indigo was limited to the governing class. As a result, the decline of the empire also led to the decline of indigo based colour traditions in Europe. It was only after Vasco da Gama’s discovery of the trade route to India that indigo was reintroduced to the European markets through export centres at Surat and the Coromandel coast. Later under the growing control of the British East India Company the trade of Bengal indigo peaked by 1895. However, with the development of synthetic indigo by Adolf von Baeyer (1865) and its placement in the European market, the indigo trade saw an inevitable collapse. The traditional method of extracting dye from the indigo plant was cumbersome and done entirely by hand. Apart from slight geographical and logistic details, the steps were mostly common.

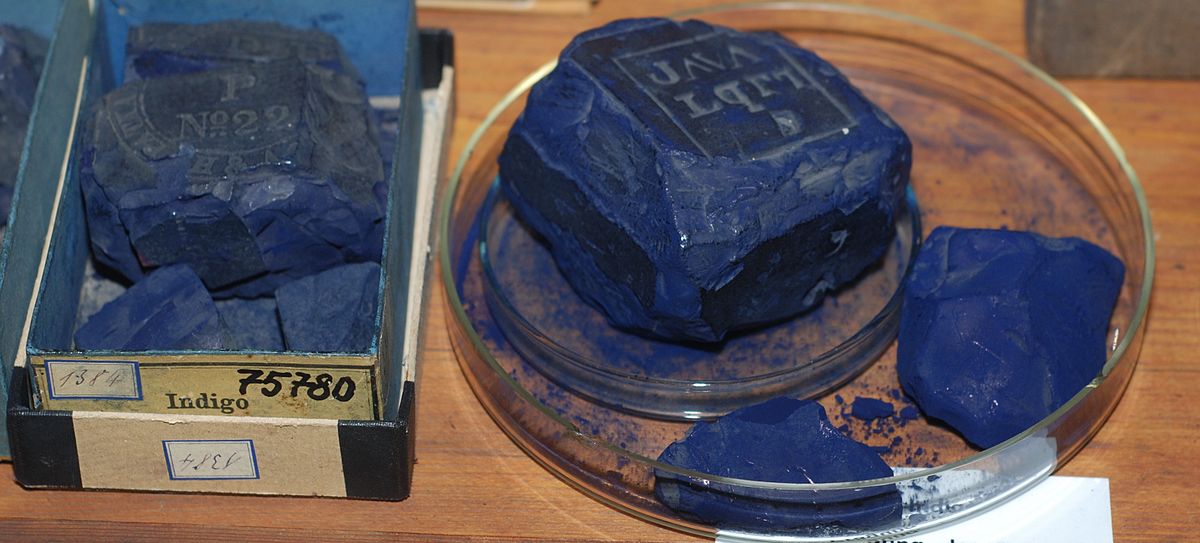

Firstly, the leaves were fermented in an alkaline solution that was vigorously beaten and left to aerate. As a result, a blue sediment was acquired which was then dried and made into blocks. Being small, compact, and profitable, indigo became a sought-after commodity in the western world and came to be known as ‘blue gold’.

Indigo has a vivid colour profile, rich and colourfast despite being a natural dye. Indigotin (trans-indigo) is the principal molecule responsible for the vibrant blue colour. Cis-Indigo (blue), indirubin (a red isomer of indigotin) and the cis-forms of indigotin and indirubin, named respectively iso-indigo (brown) and iso-indirubin (red), are other minor components which can be produced in varying proportion during the processing of indigo plants. From Indian textiles such as shibori & batik to Japanese denim, Indigo has been used in combination with other pigments. It has been observed that indigo ages beautifully, often the only remaining colour on textiles. Additionally, indigo does not require a mordant or a dye-fixer, unlike most natural dyes. A closer look at the chemical make-up of the colour producing compound in indigo explains the uniqueness and versatility of the dye. All indigo dyes possess a central double bond that connects the two heterocyclic indole ring systems with the nitrogen atoms and the carbonyl groups. Owing to this, indigo shows a bathochromic shift of energy gap between the highest occupied molecular orbital and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital. This shift relates to a specific energy exchange that corresponds to the energy of Visible-blue and UV spectral regions (in a polar solvent). Additionally, when present in the solid form the pigment is also affected by intermolecular hydrogen bonds and as a result short-range wavelengths (375-475 nm, in the visible and UV regions) are observed as deep blue colour.

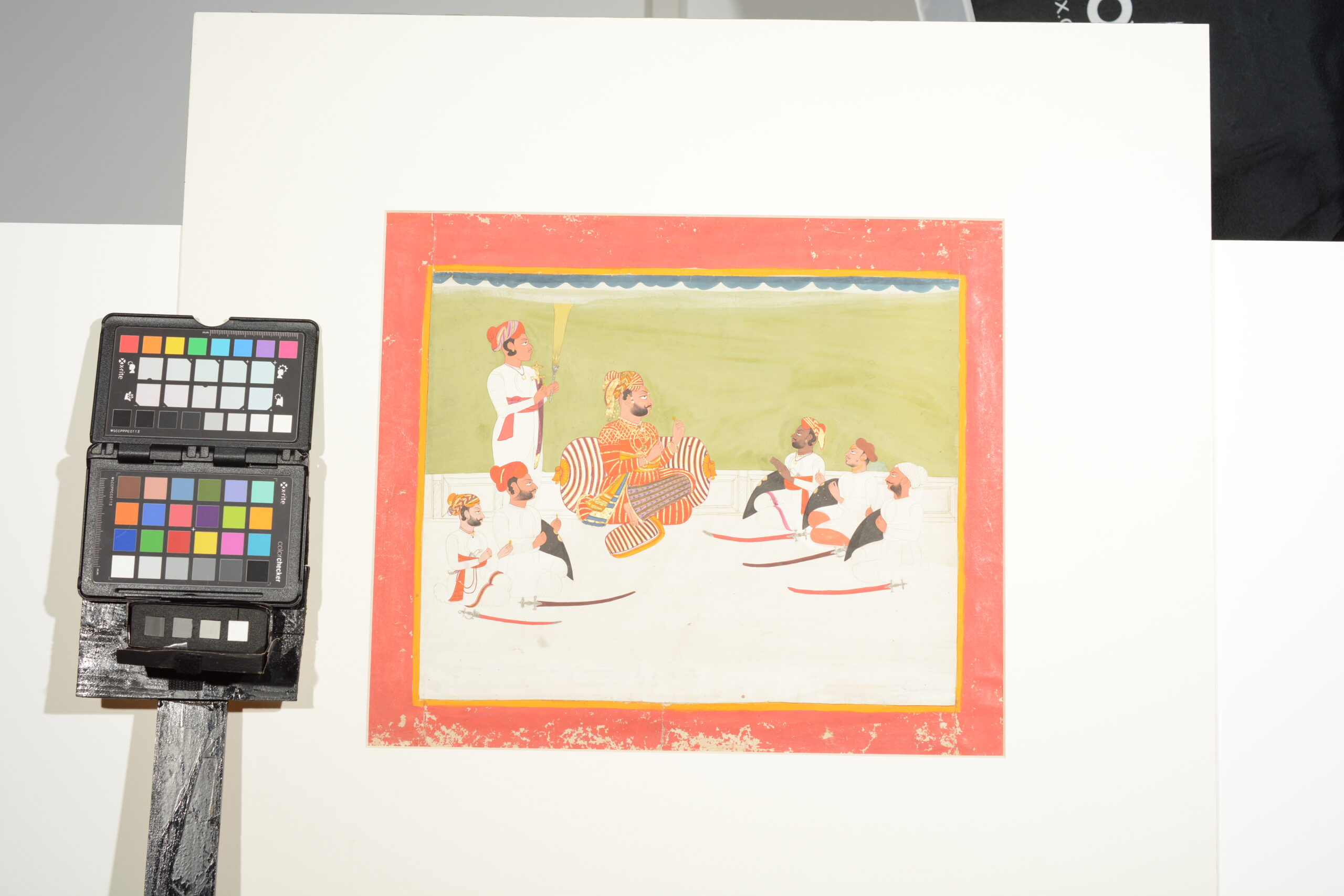

Below is a multi-spectral study of a miniature painting from the MAP collection:

From its usage in manuscripts to textile, wall paintings, ceramics , polychrome wooden objects, indigo has found expression in myriad cultures and traditions. Within the context of Indian art, indigo dye still holds a seminal role.

References:

1.Identification of natural indigo in historical textiles by GC–MS Laura Degani & Chiara Riedo & Oscar Chiantore;

2. Indigo chromophores and pigments: structure and dynamics V. V. Volkov, R. Chelli, R. Righini, C. C. Perry;

3. St. Clair, Kassia, The Secret Lives of Color. New York, Penguin Books, 2017;

4. Aldrovandi, A., Buzzegoli, E., Keller, A. and Kunzelman, D., 2005, May. Investigation of painted surfaces with a reflected UV false color technique. In Art’05—8th International Conference on “Non Destructive Investigations and Micronalysis for the Diagnostics and Conservation of the Cultural and Environmental Heritage.

***

Dhruvika Bisht is a Conservator – Restorer at MAP’s Conservation Centre. She finds joy in studying pigments and dyes, and firmly believes that colours have a life richer than humans.