Blogs

Why I Love Art: I Keep Coming Back to Nasreen Mohamedi’s Line Drawings

Harshita Bathwal

A chance encounter with one of Nasreen Mohamedi’s line drawings evoked in me, for the first time, a visceral response. Withdrawing at first, I soon learnt to completely immerse myself in her art to understand and appreciate it.

I have been drawn to Nasreen Mohamedi’s line drawings since the first year of my Masters at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU, New Delhi. For the first time, a work of art had evoked a visceral response in me. I could never quite come to terms with the sheer meticulosity that came across in her drawings. At times, I marvelled at them, while other times, I shuddered at their eeriness. It was only during my PhD, eight years later, that I truly felt the depth of Mohamedi’s lines and let myself immerse in them audaciously.

Revisiting her drawings during my PhD coincided with me initiating therapy, and learning for the first time to sit with discomfort. For the longest time, I have asked myself: “How can something as undemanding as monochromatic lines be so palpably striking?”

The first time I had noticed her drawings was at her retrospective show held in 2013 at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. Back then, Mohamedi’s drawings made me feel uncomfortable and perhaps that is why I withdrew myself from them, until now. This time, I let them affect me: I let myself feel the intense labour of her compositions, be bewildered and scared at their uncanniness. It was during those moments of intuitive engagement with her works that I felt a deep desire to let my words take the shape of her struggle.

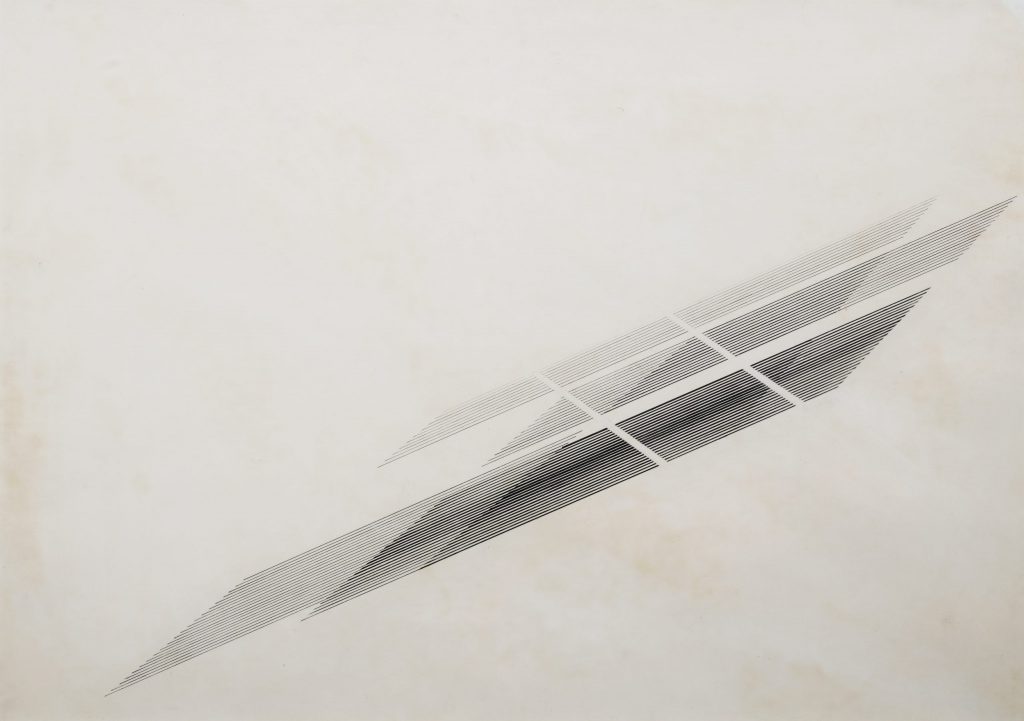

Untitled by Nasreen Mohamedi, Pen and ink on paper, Collection and image courtesy: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Well-known for her abstract line drawings, Mohamedi had faced a gradual deterioration of motor functions during the course of her life, suffering from a degenerative neurological disorder similar to Parkinson’s disease. Yet, she continued to draw until her death in 1990. As such, her drawings are more than just completed art objects; they become a way of being in time; a very intimate and bold way of relating to time through the consciousness of death. Another thing that sustains my interest in her drawings is how she uses the monochrome. Instead of merely asserting the singularity of a specific colour, she opens up a relationship of ambivalence between the marked colour and the condition of colourlessness. This, for me, makes her abstraction radically unique.

Curiously, she leaves her artworks untitled and her diary entries undated, as if implying an attitude of indifference towards gestures of meaning-making. On the other hand, there is this extraordinary diligence that stands out in her practice. This is why her works become imbued with a qualitative presence while also remaining highly ephemeral. To write about Mohamedi is to situate myself centrally in this tension rather than resolve it. And it was through my own tussle with the Covid-19 pandemic that I came back to her work. As I was forced to wait without knowing when the pandemic would end, I became uncomfortably aware of the deeper dimensions of duration, as perhaps had Mohamedi while creating her line drawings.

I began to see waiting as a meta-activity. Becoming conscious of this experience of time, of attending to time without a definitive end, became for me a part of an existential understanding of life. For me, Mohamedi’s drawings bring out the one thing that is common between objects and people: both are essentially embodiments of time. As writer and poet Harold Schweizer has aptly noted: “those who are distracted wait superficially in the dimensions of space, whereas the ill and the suffering wait deeply in the dimensions of duration”.¹

1) Schweizer, Harold, On Waiting (Routledge, 2008)

Harshita Bathwal is a researcher, writer and curator. She is currently finishing her PhD in Visual Studies from the School of Arts and Aesthetics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.