Blogs

Why I Love Art: Finding Female Histories

Anna Lynn

Weighing everyday feminisms with contemporary artist Sheela Gowda’s (mis)placed objects in installation.

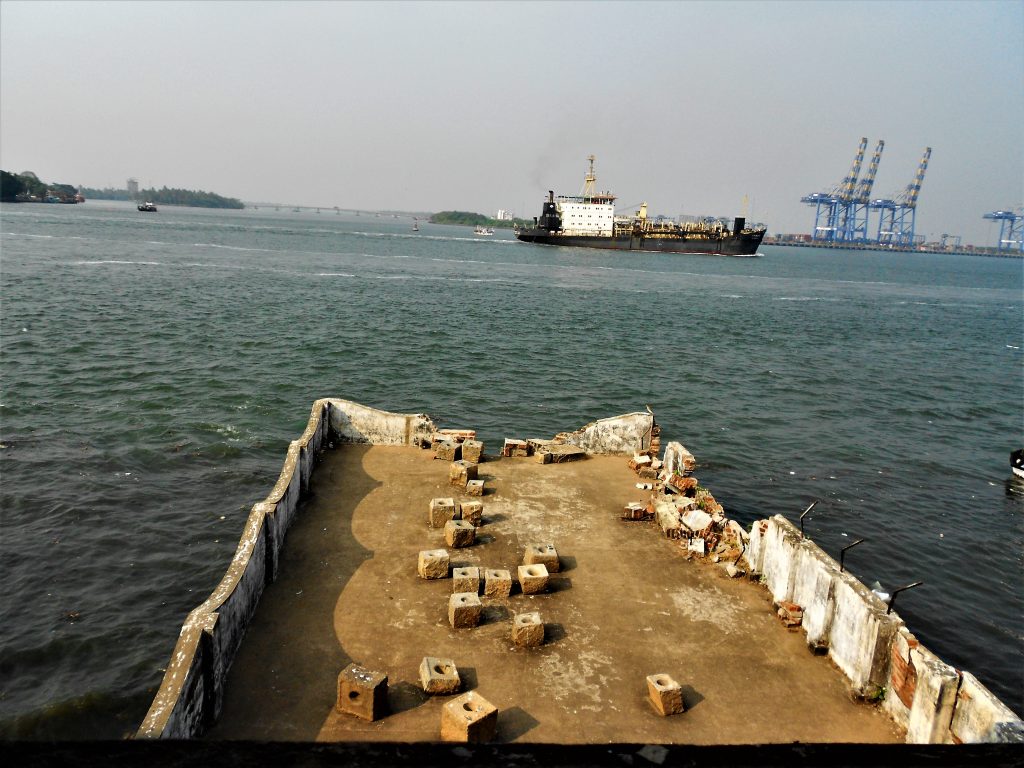

I was sixteen when my uncle took us to the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2012-13. Uninitiated in the language of art, I passed by most pieces, but occasionally some brought up personal memories. In an open courtyard, where Aspinwall House looked into the sea, more than thirty grindstones were spread around. Misplaced, almost as if offering confused rest for the weary. This is where I first beheld Sheela Gowda’s installation, Stopover.

Stopover by Sheela Gowda & Christoph Storz, 2012-13, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Aspinwall House, Fort Kochi, Installation, Grinding Stones. Photographed by the author, Anna Lynn.

Amma and Cheriamma’s faces lit in recognition. I was oblivious to female histories, to the misplaced weights that our mothers carried. “Nokikke, my mother and aunt said to us, ithu aattukallaa, ithu nammude Karimannoorilu ondu.” (Look, these are grindstones, it is there in our village, Karimannoor.)

In the arakallu, (spice grinding stone) my grandmother would place shallots, tamarind and chillies, sprinkle some turmeric and saltwater on the little depression. She would roll another stone over this until they turned to chutney. In the aatukallu, (grain grinding stone) she would grind rice,water and gram to make the maavu (batter) for appam, dosha and idli.

In placing the grindstones haphazardly, Sheela Gowda was settling the weight of memories these women carried. From their homes – as daughters, to their houses – as wives, and later – as mothers.

Years later, my research on feminism and art, led me to the Biennale. I learned that Gowda’s art and process is formed by everyday objects that fall to her gaze. In Gowda’s works, I discovered the histories of women like Amma and Cheriamma – women who work, mothers who worry, girls who leave homes, wives who know blood and sweat. I am able to trace how they placed themselves in their new homes. In looking at her work, I found clues to understanding their histories.

And Tell Him Of My Pain by Sheela Gowda, Exhibition view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2019, Courtesy of the artist and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Photo credit: Agostino Osio

The hair ropes that Gowda used in her work, the kumkum (sindoor) dipped threads, the grindstones and flower stalks, the stitched red fabric, even the sequined fabric that evoked images of washed lungis and dresses hung to dry – all reminded me of the weights placed on these women. Her (mis)placed objects seemed to pay homage to the thankless work expected of them, as our mothers and as wives.

If You Saw Desire by Sheela Gowda, 2015, Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2019, Courtesy of the artist and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Photo credit: Agostino Osio

When I read Gowda’s titles, tight smiles appear: And Tell Him of My Pain – almost an afterthought as red threads lie limp on the ground. If You Saw Desire – dreams are deferred in love, as a mother’s need to provide outweighs the pain in her arm, her spine, in memories of cotton starched stiff, hung to dry. It Stands Fallen, And That is No Lie – it is not easy for mothers to pick up their broken limbs, heaving fabric against breasts, summoning the will to survive within the bustle of everyday calls to duty. And in questioning the toxic masculinity that creates this, I find answers to my past, my mother’s past.

And That Is No Lie, 2015 & It Stands Fallen, 2015-16 by Sheela Gowda, Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2019, Courtesy of the artist and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Photo credit: Agostino Osio

In seeing Gowda’s abstract forms placed in space, there are memories of violence. In absorbing them through the memories of women before me, there is a questioning of that violence, its patriarchal depts. Where it imprints, how it is lived, how its weights are carried by bodies from generation to generation.

And just like that, the lessons I learn in feminism become lived days of Amma, Cheriamma, Mummy and mothers before us. In Gowda’s misplaced objects, I discover the placing of female weight – inherited across time and space. I also discover strength – in the iron will that forms our decisions beyond their mistakes, to create form out of discarded material.

A research scholar in Comparative Literature, Anna presses watered images into writing, as the Woolfian stream passes. She is an avid reader, interested in art, cinema and women’s writing.