Essays

The Making of the Villain in Hindi Cinema of the 1970s

Saumya Mani Tripathi

The Indian state faced a series of crises in the 70s that threatened its stability. The Bangladesh war of 1971, failed monsoon in ’72 and ’73, the drastic rise of oil prices globally, a growing recession, severe depletion of foreign reserves and growing unemployment all led to that moment of crisis. The grim economic scenario led to widespread political unrest, and a campaign of mass unrest and protests threatened to destabilize the system. The quasi-fascist government of the time further unleashed its repression by responding to the Emergency of 1977. These civilizational crises, despite being addressed in the 80s, revealed deep fractures in the national body politics. The paternalistic consumption of the state, its constitutional claims came to be questioned by the masses, and they felt that their needs and interests could never be addressed by the government. This alienation came to be refracted in cinema through the figure of the “angry young man” which was best captured by Amitabh Bachchan’s classics of angst and violent discontent.

Bachchan’s “angry young man” heroes challenged the notion that the state and its apparatus embodied the common good, offering instead a populist and violent individualism. This feeling of disenchantment became the central theme of the 70s Hindi film. Henceforth, the Bombay Hindi Cinema would begin to retreat from its goal of addressing ‘the people’ as a totality of democratic nation and egalitarian cinema. It is from there that I’ll trace the making of a villain in context of socio-economic conditions of the time and how with the rise of globalization we see multivalent facets and layered narratives of the villain in Hindi films.

With the advent of globalization and rising capitalist market, by the early 70s, the unitary structure of the Bombay film industry began to be dismantled by a series of developments that can collectively be called Bollywoodisation. Social films were replaced by masala films, and the subsequent boom of B-circuit films that emerged at a time after a vacuum was created by the decline of parallel cinema in the 80s.

Hindi film budgets expanded and star casts multiplied, and the Hindi film industry became far more integrated with other forms of media– film magazines, radio, television, advertisement, etc. The process of Bollywoodisation came to its climactic level in the socio-economic regime put in place by the liberalization of the Indian economy in the early 1990s. With the transformed laws in licensing and relaxation in import duties, liberalisation gave a jump start to the process of bourgeois democratic revolution that could be completed in this new India which was characterised by modernity, urbanisation and consumerism. The location of the new Bollywood is to be placed in this context. The integration of the Indian economy into the global marketplace and the rise of urban middle-class consumerism provided a suitable context for the wholesale restructuring of the movie industry and the emergence of a radically novel style of filmmaking. This new cinema is now much more regulated and capitalized, the division of labour and process of movie production are being professionalized and rationalized as never before, the modes of movie distribution and exhibition have been drastically altered, the film business is now incorporating high-end technology and the nature of the audience has changed dramatically. The system was very loosely structured with three sectors of production, distribution, and exhibition remaining largely autonomous and unequal in their arrangement.

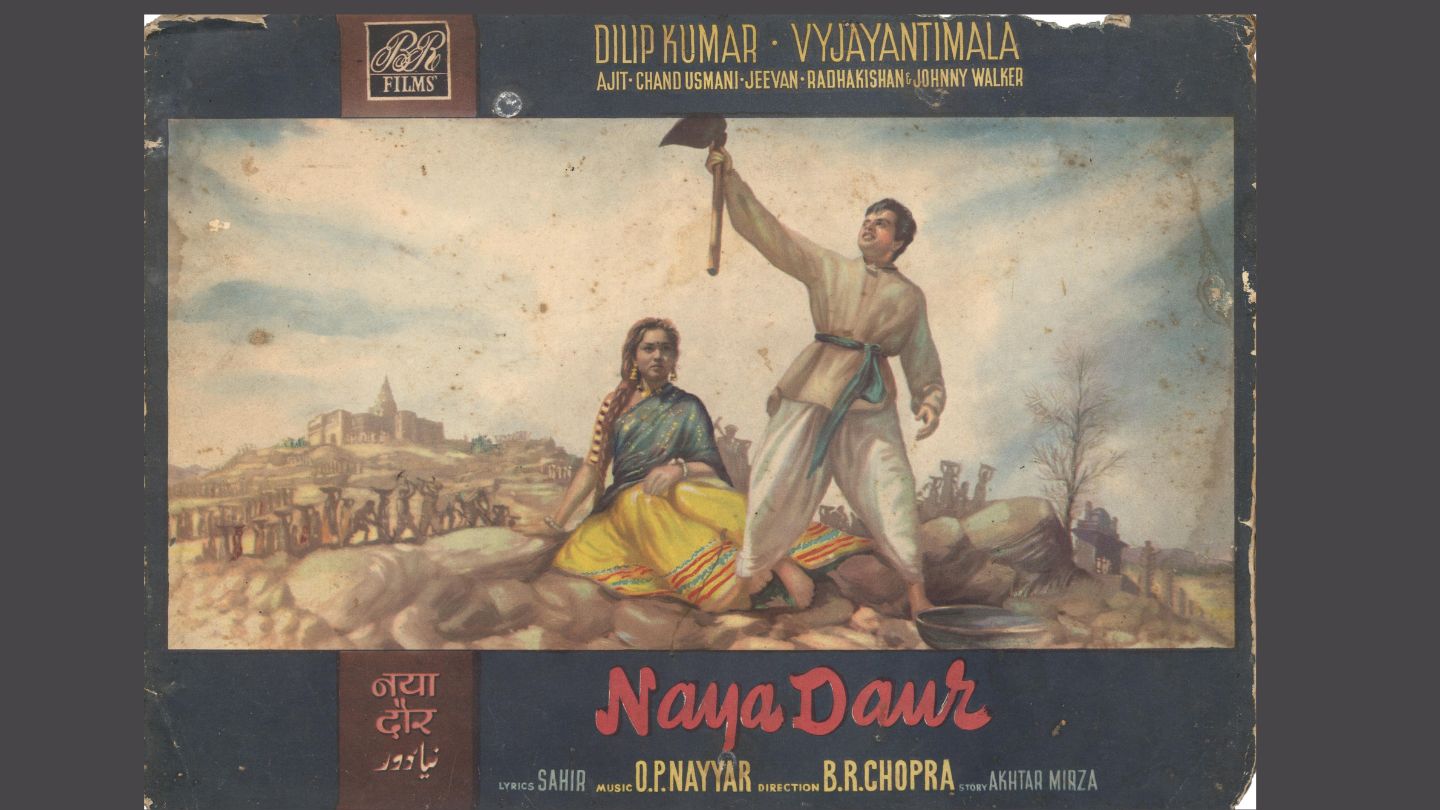

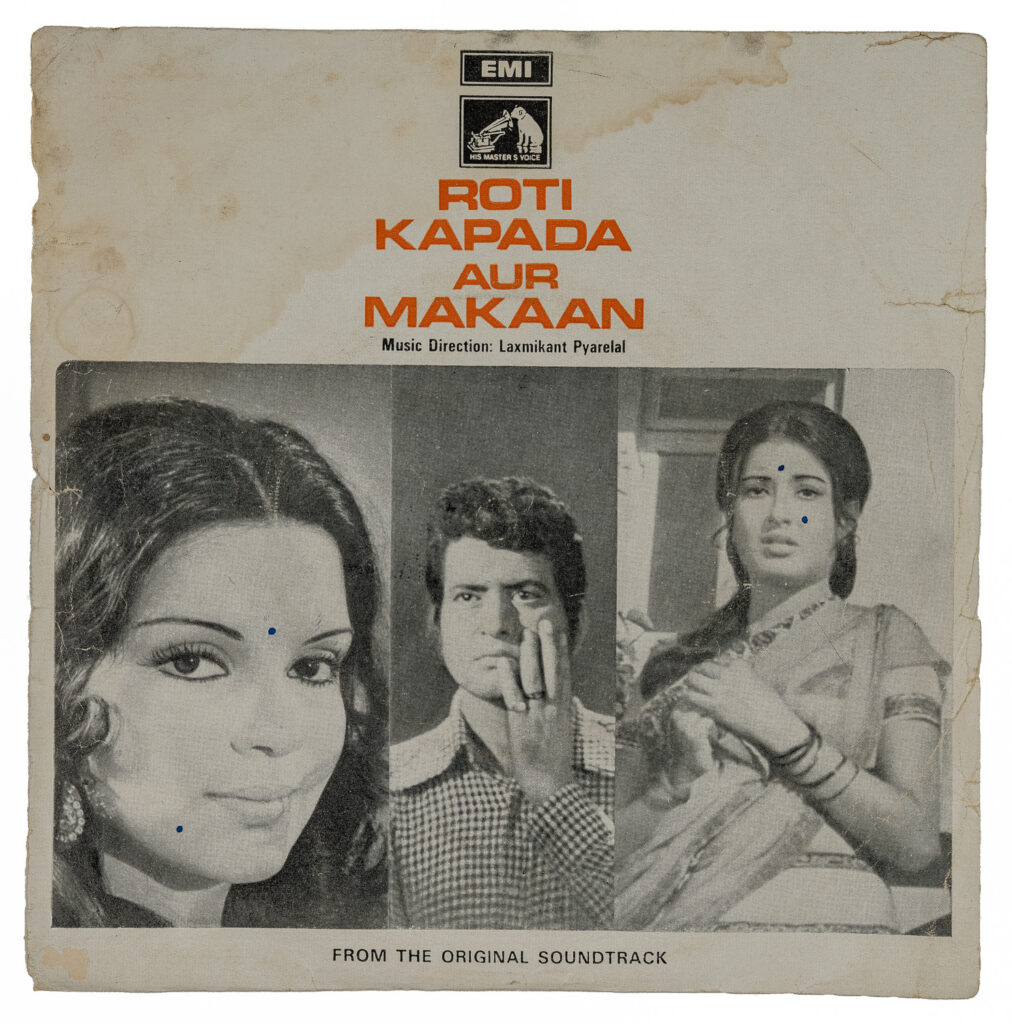

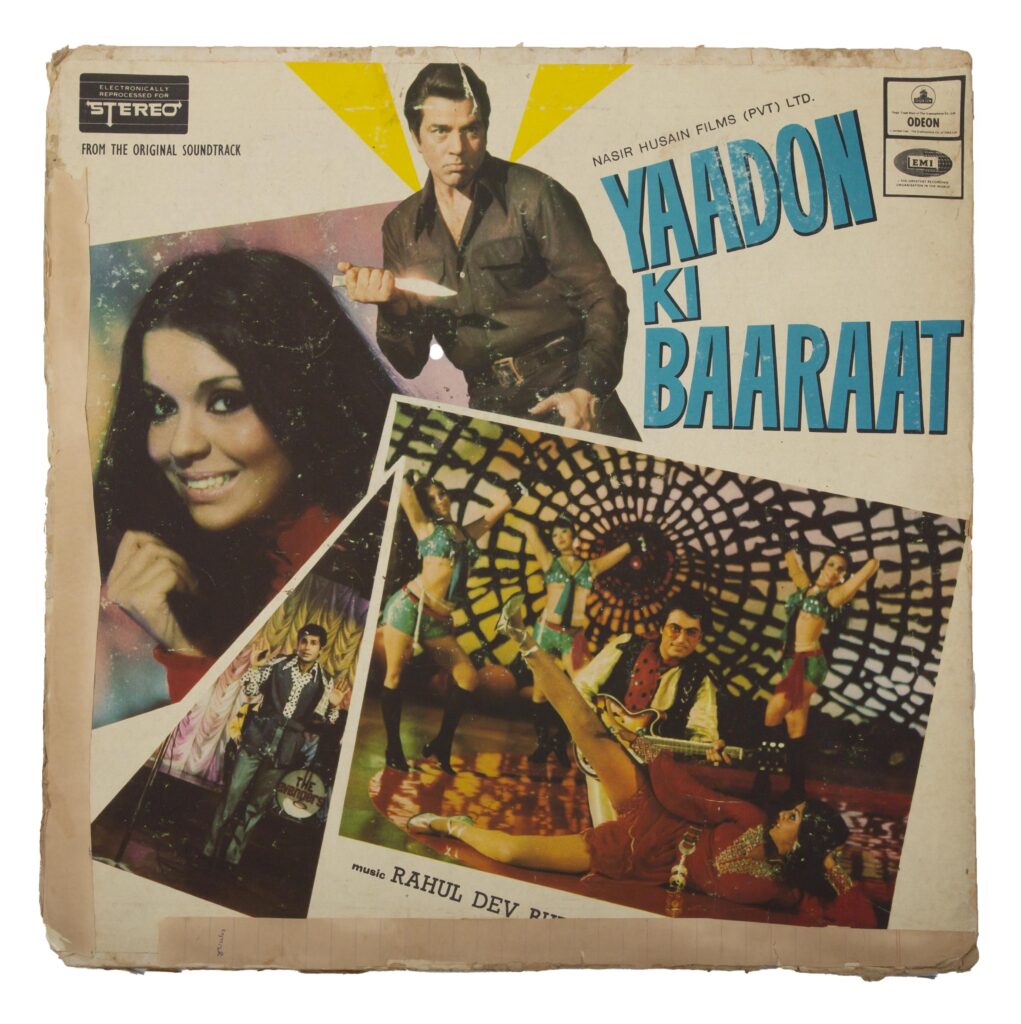

Though a fully commercial medium, Hindi cinema had to reconcile its profit-making impulses with a nationalist orientation it had inherited from its colonial past (Nehruvian socialism). Hindi cinema aspired to be a cinema that was socially responsive. It sought to remain commercially viable while drawing as large an audience as possible, and it desired to articulate the streams of modernity through its lens. The line between good and evil was blurred by the hero in the film as he too would partake in the world of evil and crime, like villains. The anti-hero can be seen as a performative figure that emerged from a cynical political culture in which the distinction between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ was getting blurred in the wake of ‘crisis of democracy’ where society witnessed the emergence of lawlessness as a popular trope in Hindi cinema. Reworking a certain vision of modernity in which the state is the sole repository of legitimate action, the hero took on the role of a smuggler in Deewar, Yaadon Ki Baraat, and Roti Kapada Aur Makaan. As sections of the state became criminalized and corrupt, a nonlegal sphere gained social legitimacy. The moral divisions between the legal and nonlegal, legitimate and illegitimate became fuzzy, opening up a reflection on the dystopian forms of urban life. The villain is represented as an embodiment of archetypal evil whose redemption is impossible. However, the moral justification of martyrdom for love, family and nation redeems the hero even if he engages in evil deeds. The state, while in a turbulent stage producing a hero that has “ strayed from his righteous path”, will restore the stability and hope of nation-building in the end.

The category of martyrdom as represented in these films is also a much-gendered category. The martyrdom of the evil hero and the vamp figure will not be emulated to the same level of worth. In the patriarchal logic of the film, both the female characters (heroine and vamp) are subservient to the world of the male characters (hero and villain). Women in the film only exist in respect to building male character heroes and are shown to have no autonomy over their life and choices. The vamp can gain redemption only by sacrificing herself for the sake of the hero or the good deed. Similarly, the death of the heroine will motivate the hero for further action of revenge or redemption. Within female characters, the vamp will be the woman available in the public domain with readiness to open sexuality, seduction and materialistic approach. She is the fallout of the city that will either be tamed or killed for the sake of the hero to redeem. For e.g.- In Roti Kapada aur Makaan both the vamp and the heroine die for the sake of the hero to help him in his nation-building agendas and to redeem him from his evil deeds of the past. There is a constant assertion of morality and saving the honour of the heroine by evoking mythology in Roti Kapada Aur Makaan. The Ram-Ravan-Sita metaphor is used continuously to characterize hero, villain and heroine; the ‘purity’ and ‘chastity’ of the heroine is preserved by establishing her as the blameless victim of her circumstances through justifying her sacrifice, but also by placing her in the trajectory of good patriarchal women who protect the men in their lives by sacrificing themselves. Because of globalisation, women were held in boundaries of tradition– any woman who comes out of the home space was shown in a bad light, and the distinction between good and bad women was characterized by the women of the outer and inner space. Women were always shown as a commodity. Globalization was intermixed with the male gaze that offered them voyeuristic pleasures. Women’s presence in the city was always seen as a source of constant apprehension and danger in these films. The concept of ‘bazaar’ was brought to its climactic heights by globalization where fetishism was played out on screen through the commodification of the female body as well as the physical space. The female body became the space of contestation of moral, cultural and national issues. The erotic performances, the exotic vulgar sensuous bodies that were shown on screen came to be attached with the realm of the villain, although the hero often inhabited them as well. A particular sequence in Roti Kapada aur Makaan where the exotic dancers are dancing, and the images of fire around the border and death have juxtaposed the contradiction of utility and servitude of body– one laid out to the sexual pleasure of the corrupt debauchery and other serving to the pain of the nation building. The category of nude is highly gendered in these films viewed from the eyes of the male voyeur.

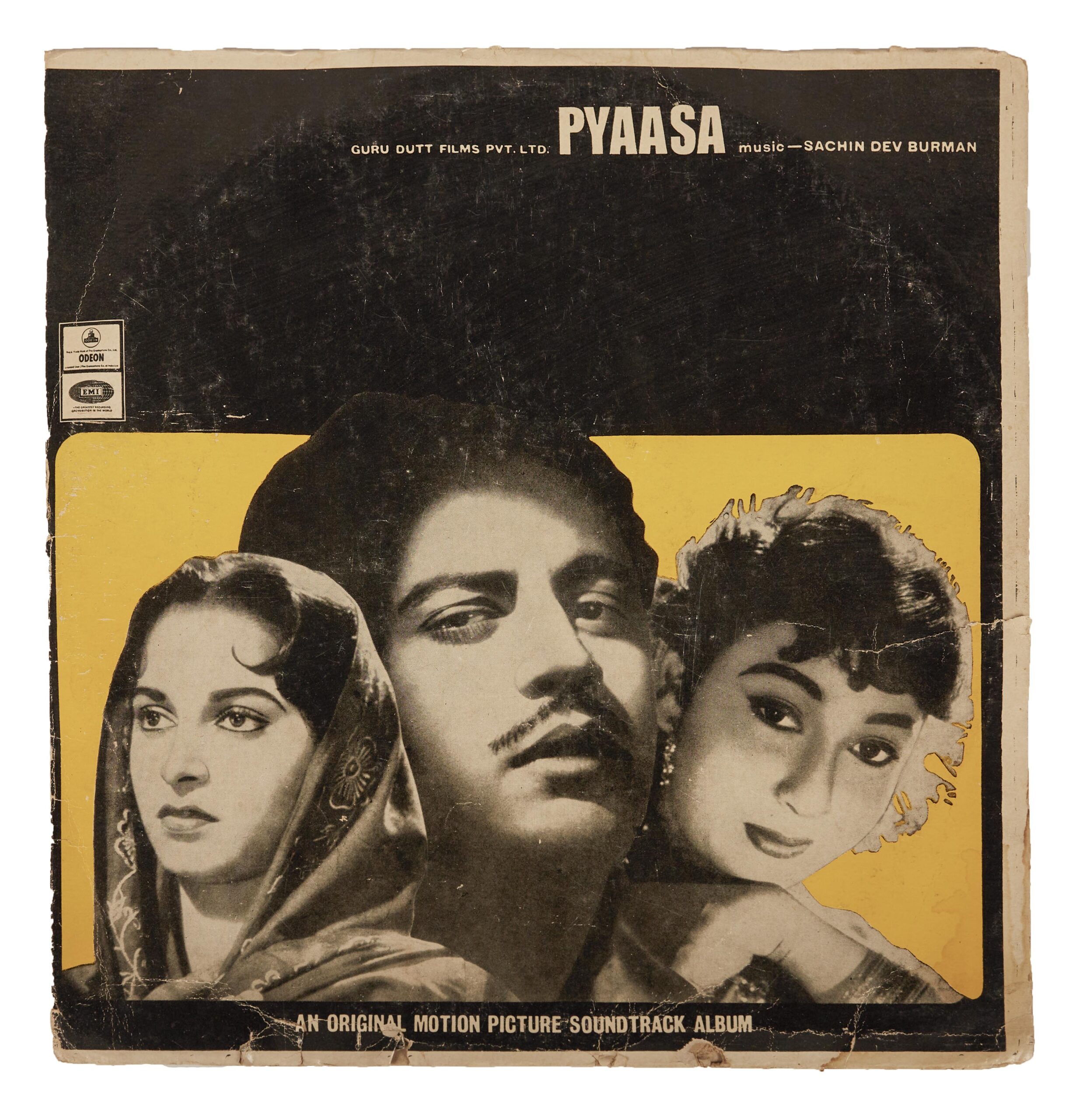

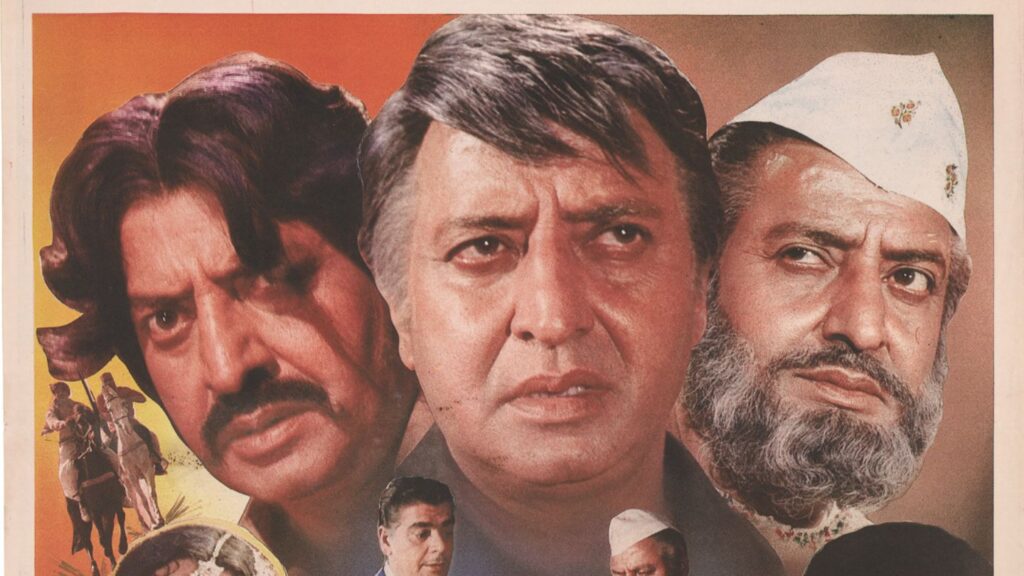

The villain in 70s cinema is always endowed with larger than life qualities. They are established as evil at the very moment of their appearance by the mise en scene. They appear in various forms;from oppressive social beliefs and practices to oppressive authoritative social identities . The traditional villains appear in Hindi films as munims(moneylenders), contractors at the work site, upper caste landlords, insensitive urban rich, politicians, whimsical cruel kings, corrupt officials, underworld mafias and smugglers. They are shown as an aberration in an otherwise ethical society who amass wealth with greed and insatiable appetite. In the cinema of the 70s, the villain whose prima donna figure is Ajeet Singh adorns the role of the smuggler who continues to retain an unreal personality and live in a hyper material glamorous space of the claustrophobic denizens of the universe. The excess of his character and materiality around him gives it an unusual nightmarish outlook which exists in liminality- not completely real or virtual but somewhere in a hallucinatory dizzy atmosphere of too much light and darkness.

The idea of proportional justice must be attained in the course of the film. The intensity of trauma that the hero went through has to be avenged equally through materiality than symbolically. So the hero also elevates to the status of materiality equal to villain which is played out through the change in the environment concerning his material status, light, sound, color, speed, not just at the level of narrative but also in its affective presence. The material wealth of the hero increases throughout the timeline, and in the end, it’s comparatively higher even after his return to the domain of ethics. There is massive orchestration of space and who controls that space in the villain’s domain. This space also becomes the liminal space of the intersection of legality and illegality. E.g., in Yaadon Ki Baraat- the hotel becomes the space that is bordered by the space of legality but regulated by the space of lawlessness by the owner Ajeet Singh. The villain and his space thus become a site of semi-legal liminal existence.

The villain is seen as a reflection of society’s own traumatic self, the ‘other’ who is the product of the catastrophes of the times. He is seen as the pathology of modernity and problematized as a psychopathic individual’s existence in the normative structure of society. He is seen as a morally ambiguous, socially dubious figure of society which needs nurturing from society to be brought back to the normal self. These films allow us to do secular readings of violence generated by different hierarchies in the system that produces its annihilators. The hero thus becomes a site of reform which can be reconstituted in the society despite being pushed to margins once. He is seen as an unintended site of pathology in a sense that all humans are susceptible to being corrupt and violent and he must be recuperated from this condition. In Yaadon Ki Baarat –the character of Shankar is pushed to the edge of the criminal world as an alternative to hunger and poverty, he however maintains his virtues of being a protective paternal figure by rescuing and defending women’s honour, by being honest in his dealings and is brought to reconciliation by the fraternal love of the family. The ‘dosti’ metaphor is being played out to bring back a character and to tame him into society’s normative structure. The reconciliation of the private domain was sought in the public domain of the state.

The villain, however, cannot be redeemed at any cost, he is the oedipal figure – an aberration to the society who cannot be accepted, tamed or reconstituted in the society. The characterization of the ‘other’ takes place by hyper-exaggeration of his characteristics, exoticization of his body, making him a composite figure caught between many worlds. This out of sync character is a matrix of mythic and real figures. He tries to run faster than everybody else and thus is caught in a time warp making him a surreal character. He uses the space of both urban and rural to create his mythic dimension. The use of an excess of colour, the glamour of shiny objects, the exposure of exotic bodies, adoption of technology and speed in his environment, the use of hyper materiality make him the subject of fantastic creation. The landscape of the village is however not a nostalgic past or a classical metaphor of innocence and home. Instead, the village of imagination is looked through the prism of urban experience. The village is now inconceivable as space without the gaze of the city.This trope reached its peak in later Amitabh Bachchan films like Agneepath where village Mandwa is the metaphorical village of imagination always overshadowed by the gaze of the city Mumbai .

The villain of the 70s cinema functions under the logic of voyeurism and his gaze is seen as a projection of the secret desires of the viewer. The body comes out in search of the voyeur who is sublimated and finally finished on screen. This personified figure is shown to be resistant to the growth of society and is deeply embedded in the psyche of the society and has to be confronted and killed on screen. The audience thus feels exposed, vulnerable and at the same time safe after their ‘inner desire’ is killed on screen and they can come out safe.This symbiosis of globalization and the existence of the villain on screen gets amplified in the contemporary situation with a rise of ultra capitalism and multiplex theatres. Now the films no longer have a vendetta mass appeal like that of Bachchan’s films but the villain himself has been completely transformed into the voyeur hero who plays out the repressed secret desires on screen and gives the viewer the pleasure of the voyeur. The protagonists of any age embody the morality of the times and with changing times and context, we see the emergence of new definitions of heroes and villains.

References

Madhava Prasad, The ideology of the Hindi film: A Historical Reconstruction, Oxford university Press, 1998

Rajani Mazumdar, Bombay cinema an Archive of the City Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press, 2007

Sangita Gopal, “Introduction”, Conjugations: Marriage and form in New Bollywood Cinema Chicago:University of Chicago Press, 1-22

Valentina Vitali, Hindi Action Cinema:industries, Narratives, bodies New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008

Anil Zankar, ‘Heroes and Villains: Good versus Evil’ in Encyclopedia of Hindi Cinema, New Delhi: Encyclopedia Britannica, 2003

Ashish Rajadhyaksha, “ The Bollywoodization” of Indian Cinema:cultural nationalism in a global arena, Inter Asia Cultural Studies, vol. 4, 2003