Essays

From Nightclubs to Silver Screens: The Disco Phenomenon in India

Anusha Vikram

This article by MAP’s Anusha Vikram explores the humble beginnings of the disco genre in India. On the coattails space race that was capturing India’s imagination, came a musical revolution that changed how music is approached in the film industry. Trace the revolution that brought the oomph to Indian shores!

To explore what the disco era in the Hindi film industry and other music that inspired disco sounds like you can listen to this curated playlist on Spotify.

***

South-Asian pop culture embraced a cosmic wave in the 1970s and 1980s clad with glitter, luscious lipstick, and flowy dance moves. This era of decadence and indulgence has a faint connection to electro-science experiments, which might carry the answer to the question; why did disco sound and look the way it did? In 1970, an experimental group of artists visited India and this may have perhaps sparked the early beginnings of a collaboration between sound engineers and musicians in the music industry. Geeta Sarabhai, a musician herself is credited with encouraging collaborations between Western and Indian music. She introduced the synthesiser with the help of David Tudor an American musician at the National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad. Around the same time, her brother, Vikram Sarabhai was heading space research in the National Committee for Space Research. Artists from Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T) were funded by the Rockefeller Foundation on a trip to India under the “American Artists in India” program in 1970. The Sarabhai siblings were enthusiastic about projects with E.A.T.

Although this collaboration was contained within the institutional walls of the NID Ahmedabad, the technology eventually found its way to mainstream film music. In the year 1980, the Indian government applied economic liberalisation by loosening restrictions on business creation and import controls – this particular moment in India’s economic history changed the way we saw music.

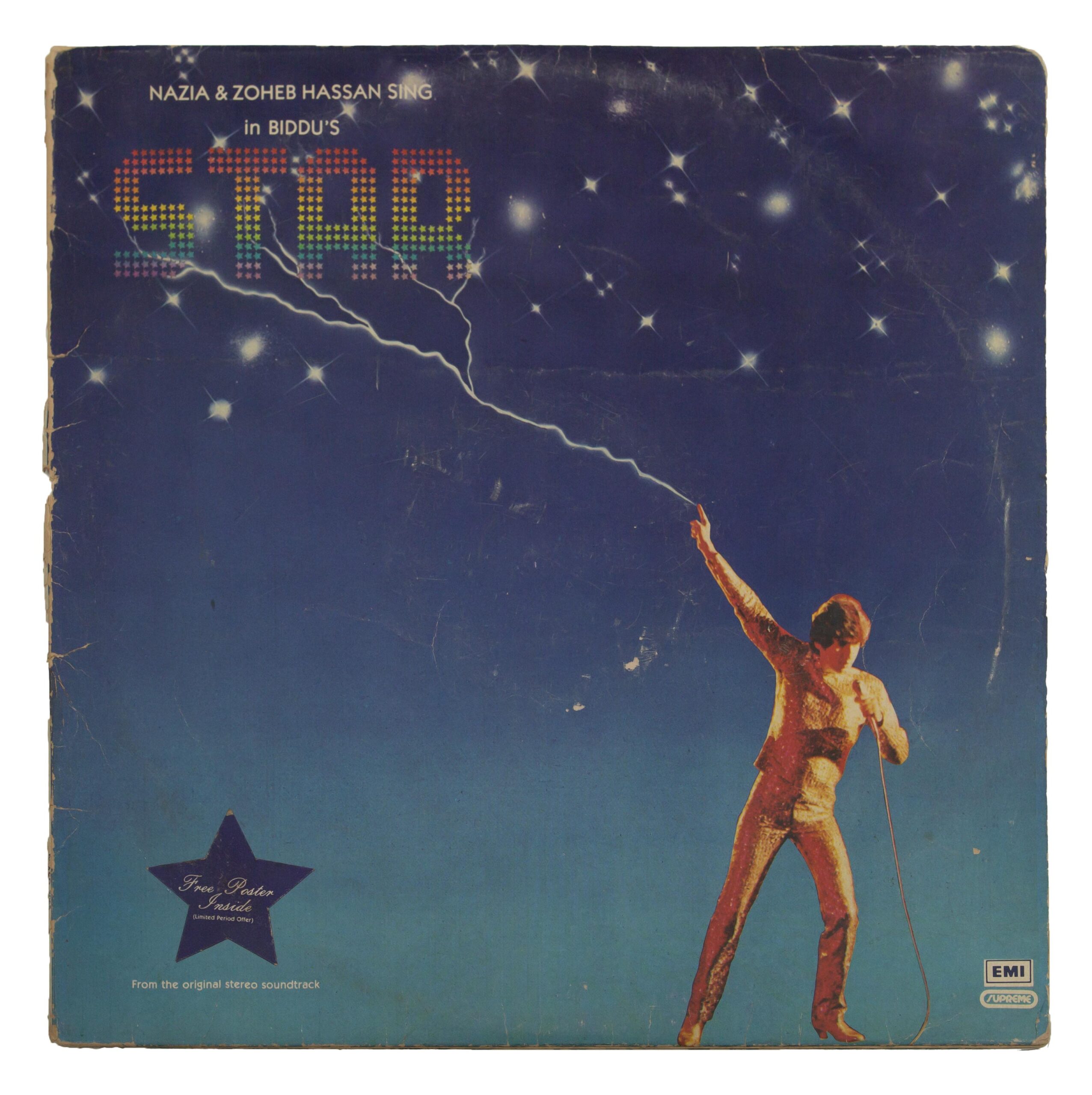

The same year came the movie ‘Qurbani’ – featuring a 15-year-old Pakistani singer Nazia Hassan on a song called “Aap Jaisa Koi” composed by Bangalore-born musician Biddu Appaiah. He worked with Nazia on “Disco Deewane” – a disco-pop album that ended up selling 100,000 records within a day of its release in Mumbai alone. The album not only brought about the disco wave to India but also heavily influenced the album art, which was inspired by the space missions happening around the world. Space missions changed the way people saw the world. They made humans wonder about the cosmos, the expanse of the universe, and other living beings on other planets. Futurism advocated speed, technology, and youth culture.

The new India was rapidly modernising and technology was at the forefront. Film music reflected this new development and extensively used electro-music equipment in addition to sound and light effects that embodied the futuristic aesthetic of their time. This disco wave wasn’t just about catchy tunes but a cultural shift. Space missions ignited imaginations, and futurism became the zeitgeist. Film music embraced electronic instruments and sound effects, creating a futuristic soundscape. Disco music’s accessibility fostered multiple collaborations between composers and technicians, empowering the latter’s creative input. Orchestra musicians, familiar with Western music and technology, became key contributors to the movement.

Charanjith Singh, an electronic composer, mastered electronic music in India and brought his acid-electro tunes through the album Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat. Singh had a prominent presence in the Hindi film industry as a guitar player for composers like R. D. Burman, Kishore Kumar, Laxmikant-Pyarelal, and Shankar-Jaikishan. His passion for music extended beyond film songs and he released several albums that were electronic covers of film songs. Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat was an album he released in 1982, an original composition. The album was commercially unsuccessful but gained a well-deserved re-release in 2002. Edo Bouman, a record collector discovered the album in a record shop in Delhi and re-released it through his UK-based label Bombay Connection. Singh is credited as an acid-house pioneer as his experiment in Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat predates the first acid-house record – often regarded as Phuture’s Acid Trax. Singh becomes an important connection between electronic music enthusiasts and the film industry. The influence of such technicians in the film industry is largely untraceable and undocumented. The film music of the 1980s extensively used electro-music equipment in addition to sound and light effects that embody the futuristic aesthetic of their time.

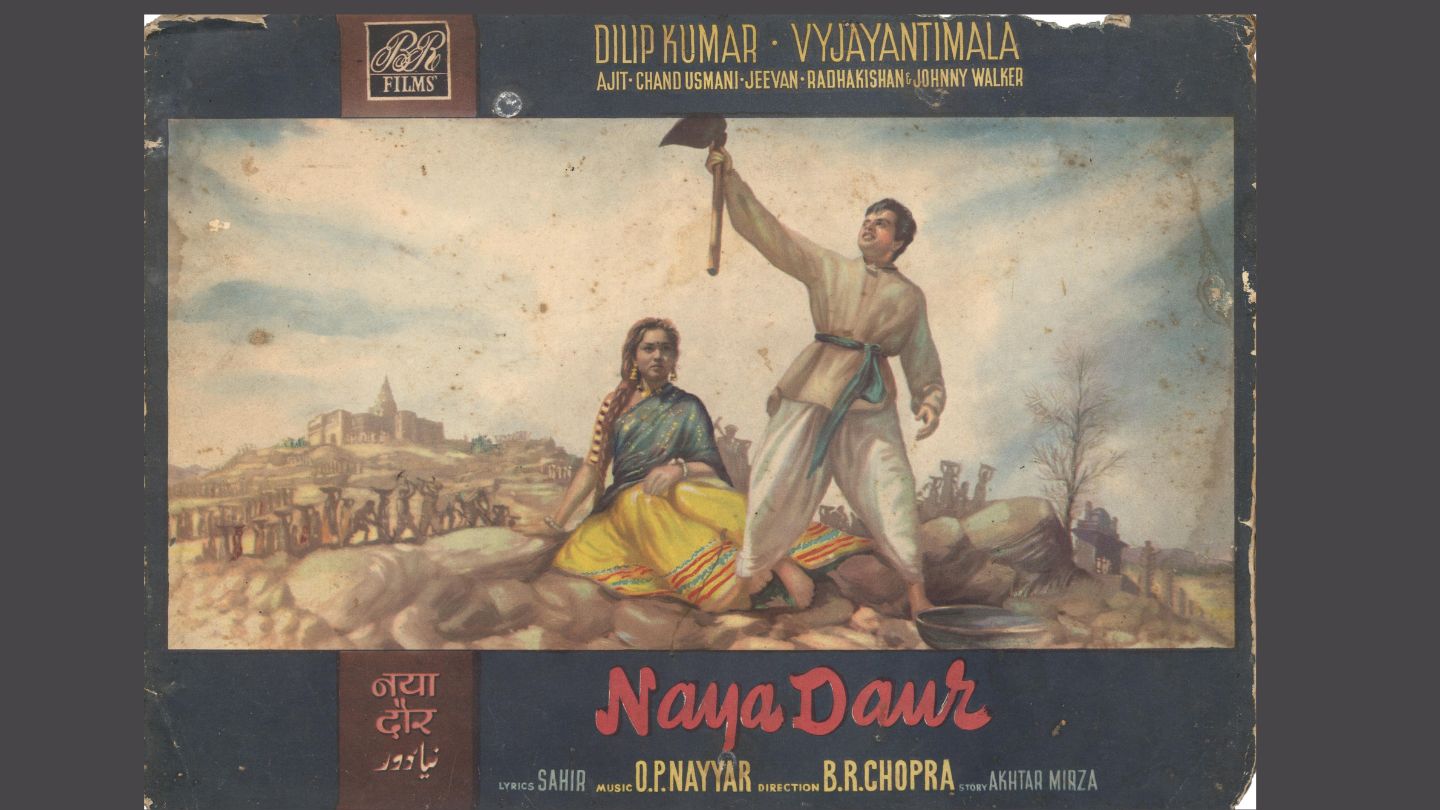

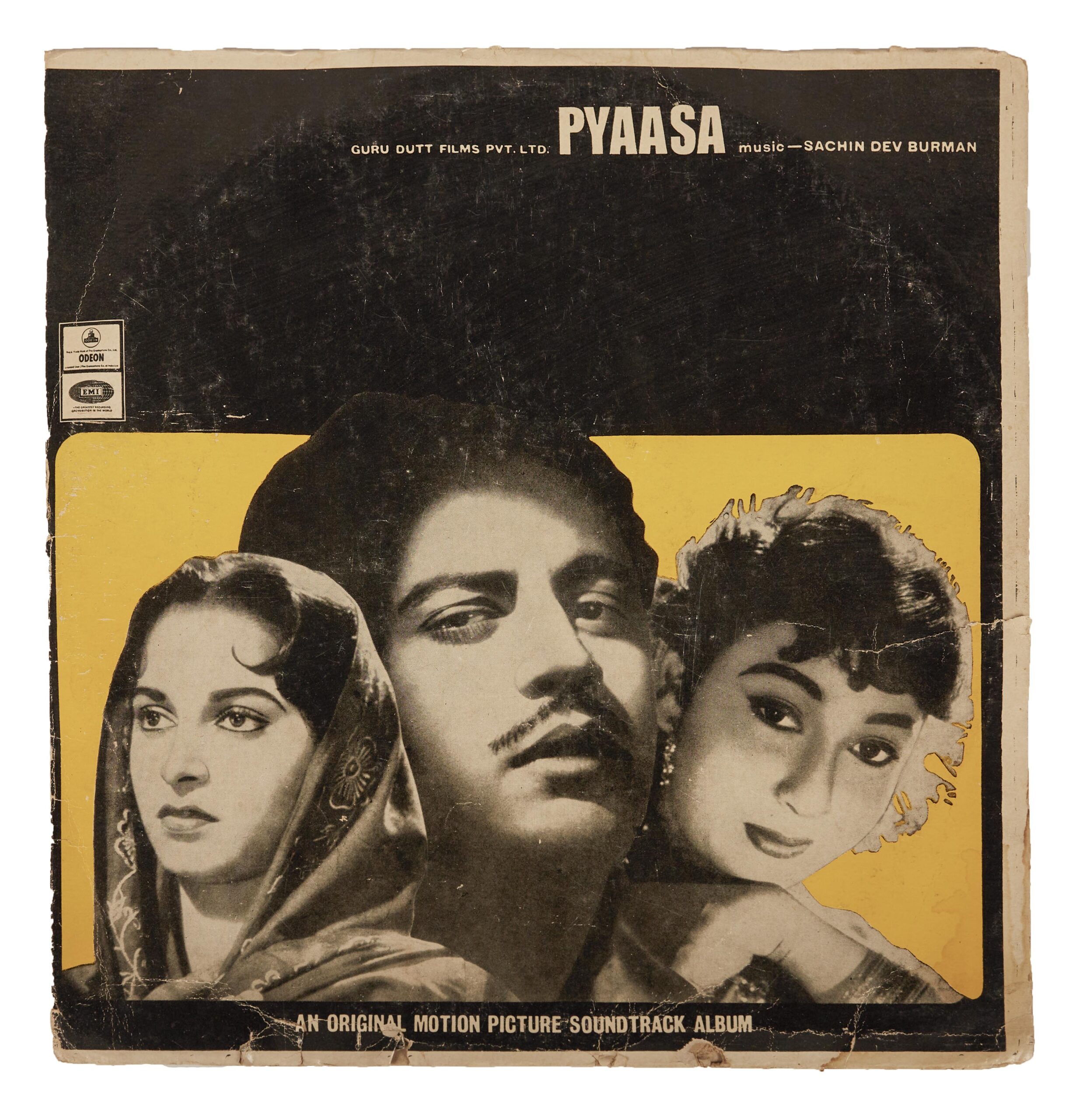

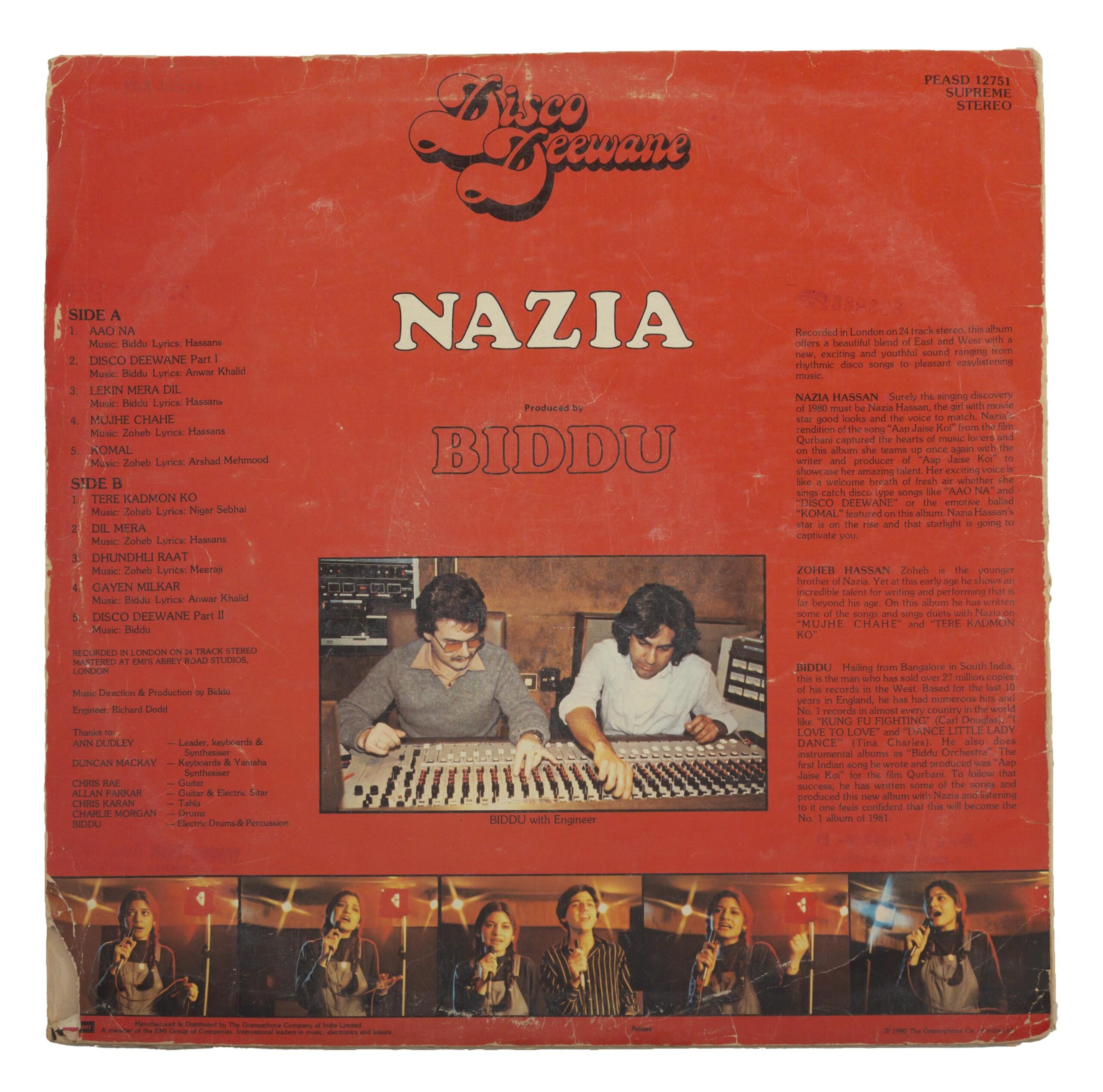

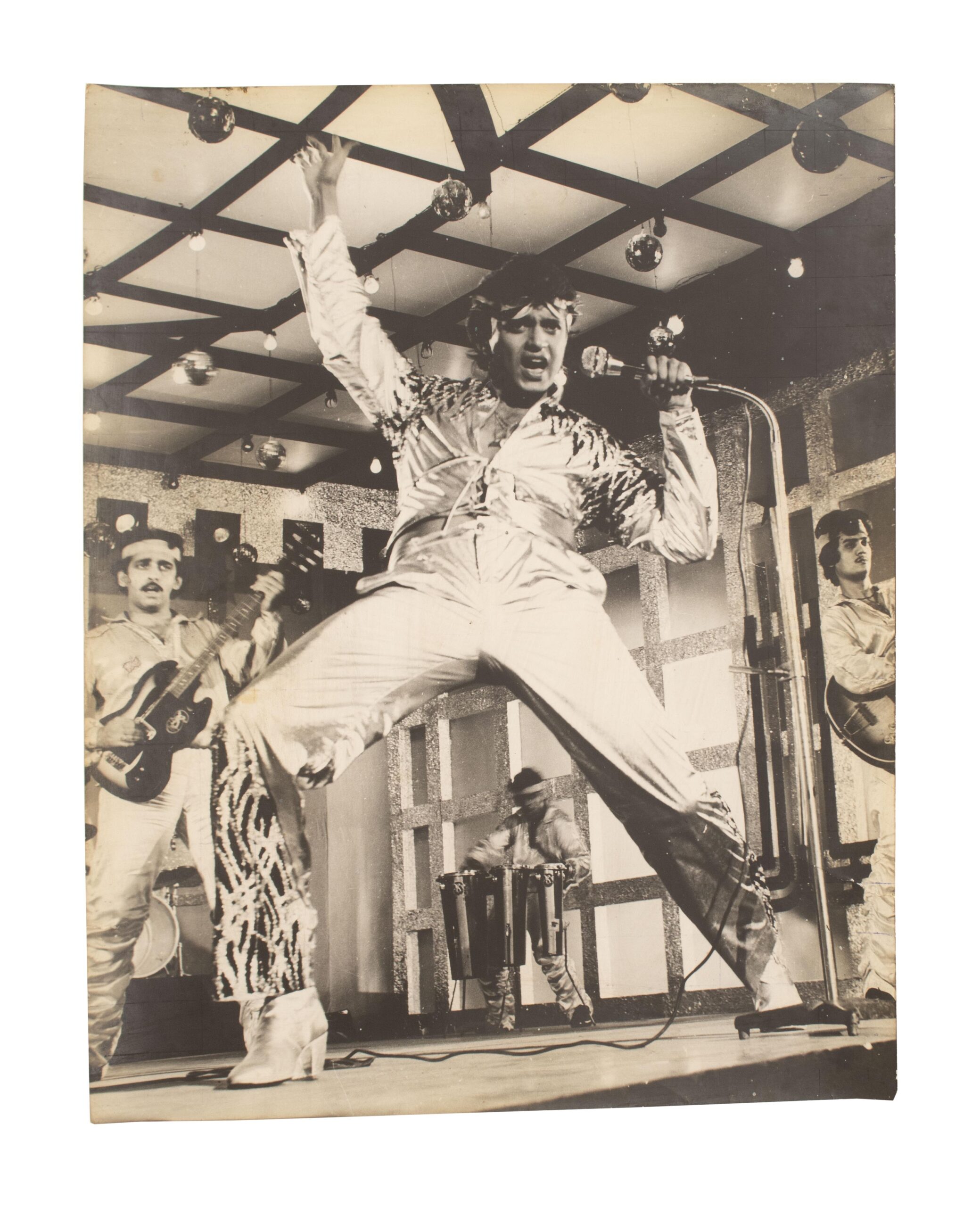

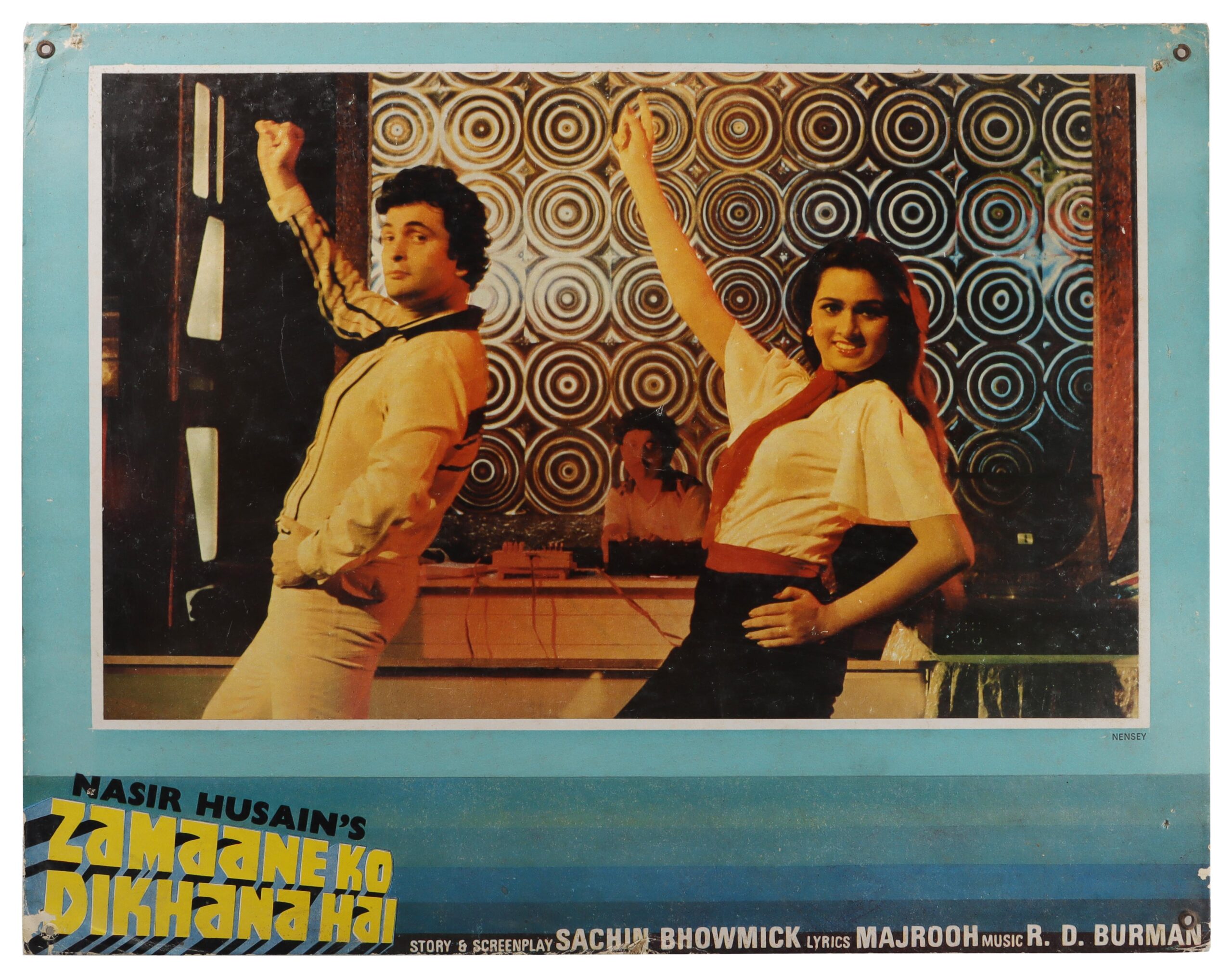

In some vinyl covers, the space aesthetic is dominant and a core visual language. The vinyl cover of the film Star for example has cutouts of the lead actors Kumar Gaurav and Rati Agnihotri floating in shiny outfits against a starry background. We are reintroduced to the brilliance of Biddu, who composed the music and directed the film. The album cover of Disco Dancer features an iconic image of the lead actor Mithun Chakraborty. In the background, a starry night sky-like effect highlights the disco-star image of Chakraborty. The back cover of the same album features Chakraborty dancing with Kalpana Iyer against two beaming lights that look like stars glaring in the background. In the lobby card of the film Zaamane Ko Dikhana Hai, the leading stars Rishi Kapoor and Padmini Kholapure are featured in a popular disco-dance pose. In the background, a clumsy set-up of wires running and a seated technician bathed in red light is present. The album cover of Armaan features two actors dressed like celestial beings. Both actors are depicted against a backdrop of an otherworldly space. Interestingly, they are placing their hands on a star-like object that floats in the sky. The image literally illustrates the popular saying ‘to reach for the stars’. The visual iconography associated with synth-pop and disco dance songs therefore featured glitzy lights, shimmering dance costumes, and machines. Its appeal catered to a large audience and became a highly relatable culture for modernity and youth.

The accessibility of minimal beats was further explored by the founder of the music label T-series, Gulshan Kumar, who introduced the concept of ‘jhankar beats’. Jhankar beats were essentially sounds produced on Roland SPD-11, an electronic portable drum. These beats were then overlaid onto film songs. These budget-friendly cassettes gained immense popularity among public transport operators like taxi or auto-rickshaw drivers. This remix’s high-selling rate was mainly fueled by the fact that cassettes with Jhankar beats cost half as much as the original soundtrack album. Gulshan Kumar exploited the loophole in music reproduction rights while challenging the tyranny of leading music labels in the 80s and 90s. Several music enthusiasts express strong repulsion towards the Jhankar beats edition, but one cannot deny that it got people grooving to its catchy beats.

Disco music epitomised youth culture and was among the earliest memories of a liberal space that enabled a wild and free environment. Disco’s cosmopolitan sensibilities are intermeshed with various music styles forming its unique fusion in Indian modern music. These songs continue to remain relevant because generations of people soak in the quality of nostalgia that this music thrives on. Synth-pop and disco make occasional comebacks in film scores and background music even today. Composers like Ilaiyaraaja are masters in mixing synth-pop and electro-funk music to make groovy tunes that are a class apart. In the galaxy of Hindi film music, Disco music is a bright shining star for being an early collaboration of technology and art in India.

References and Notes:

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T) official website: https://www.experimentsinartandtechnology.org/

East of Borneo. “Subcontinental Synth: David Tudor and the First Moog in India — Alexander Keefe,” April 30, 2013: https://eastofborneo.org/articles/subcontinental-synth-david-tudor-and-the-first-moog-in-india/

Paperclip. “Jhankar Beats — Paperclip,” 2023: https://thepaperclip.in/jhankar-beats/

Bhatia, Siddharth. India Psychedelic: The Story of Rocking Generation, 2014

Appaiah, Biddu. Made in India: Adventures of a Lifetime, 2015

***

Anusha Vikram is a Project Coordinator for a digitisation project at MAP. She has recently found a deep interest in film ephemera through MAP’s vast collection.