Essays

Sculpture isn’t still: Meera Mukherjee and Jaidev Baghel talk to each other in dhokra

Conversations between artists aren’t easy to kindle while they are alive; practising and presenting. Setting up their work to speak to each other, after their passing, is a whole other challenge. At Outside In: Meera Mukherjee and Jaidev Baghel, an exhibition at the Museum of Art & Photography, the crafted exchange between these two iconic, late modernist Indian sculptors is lively, thrilling and awe-inspiring.

In their lifetime, the sculptors Meera Mukherjee and Jaidev Baghel were completely obsessed with the indigenous lost wax method of bronze sculpting, now known as Bastar dhokra. Mukherjee’s interest in the lost wax technique was piqued at Munich in 1953, after dropping out from painting to pursue sculpture, at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich on an Indo-German fellowship, and later, apprenticed with Bastar sculptors to develop her own language with the medium. Baghel, on the other hand, was born into the community of Gadhwa artisans in Kondagaon, Chhattisgarh. He learnt the dhokra technique from the age of eight from his father, Sirman Baghel. Their individual journeys in this metal casting technique, their hesitation and the eventual honing of their skills form the spine that allows these two modernist sculptors who never encountered each other’s practices to talk to one another at this exhibition.

Before the emergence of these two artists, the dhokra technique was mostly used by indigenous artisans across Eastern and Central India to make community deities for their religious festivals and rituals, besides jewellery and other daily utility objects. But in 1977, a twenty-year-old Baghel cast Dhankul Puja, a sculptural tableau of the annual New Moon ceremony for prosperity celebrated in Bastar. This was the winning entry of the National Craftsman Award, and with this work, Baghel shifted the potential of this technique to show stories from his ordinary, everyday life. He began to singularly craft this technique to show stories from his position in the world as an adivasi. With Mukherjee, who incidentally apprenticed in the technique with Jaidev’s father Sirman Baghel in the early 60s, the initial approach itself was artistic. Baghel pushed the structural language of the technique in order to show a narrative (or represent a figure) and Mukherjee studied in her approach from the very beginning, allowing for the materiality of the metal and the markings of the process to mould her narratives of the mundane too.

The 27 sculptures and five textile pieces at Outside In: Meera Mukherjee and Jaidev Baghel undo the dull debates between questions of the modern and the traditional, between artist and artisan. Instead, collectively the work in the exhibition presents the ongoing, constant conversation between these two categories and these two types of practitioners. Take Mukherjee’s Mother and Child and Baghel’s Madin with Her Child, where the themes align but their approaches converge and diverge at points. Baghel’s sculpture is executed in his signature style, the torso and limbs are elongated, the figure is intricately embellished with all the glorious jewels and markers of an adivasi woman holding her child on her knee.

Mukherjee’s rendition has the mother and child like a blob merged together in a loving embrace. In both, the command over the technique is obvious, but they used them for different ends. Baghel’s statuesque figure maintains a strict frontality, while Mukherjee’s sculpture wants to be seen from all sides. And while Baghel is invested in seamlessly joining his sculptures together, Mukherjee consciously, cleverly works the seams into her narrative. But they – Mukherjee and Baghel – converge again, in their respect and regard for the intensive labour needed to produce these sculptures. Instead of entirely polishing away the traditional wax thread (mom sutta) technique used to build up these sculptures, they both leave them behind and use these lines to shape their sculptures and their stories. In Baghel’s sculptures, these result in fine ornamentation and in Mukherjee’s sculptures, it lends to their fluidity.

Another stream of dialogue gushing through these sculptures finds visibility in the difference of colour between Baghel and Mukherjee’s sculptures. Baghel’s work has a customary golden sheen, a tone masterfully achieved to mask the multiple sources of the metal, while Mukherjee factors the end result of firing a particular metal into the narrative of the work. Take her Coal Miners, the black tones of the sculpture contribute to the world-building, speaking to the darkness and danger of mining coal. The whole sculpture captures the experience, while the embellished details elaborate on it.

At Outside In: Meera Mukherjee and Jaidev Baghel, the real victors are the materiality of metal, and the spectators experiencing these figures. Baghel’s sculptures are striking – glorious, grand and grounded in the adivasi stories he grew up listening to, and Mukherjee’s work is subtle – light, liquid and lyrical in their telling of ordinary people’s stories. Both were interested in the ordinary but were such experts in their technique that they transformed them into exquisite, extraordinary work.

BOX

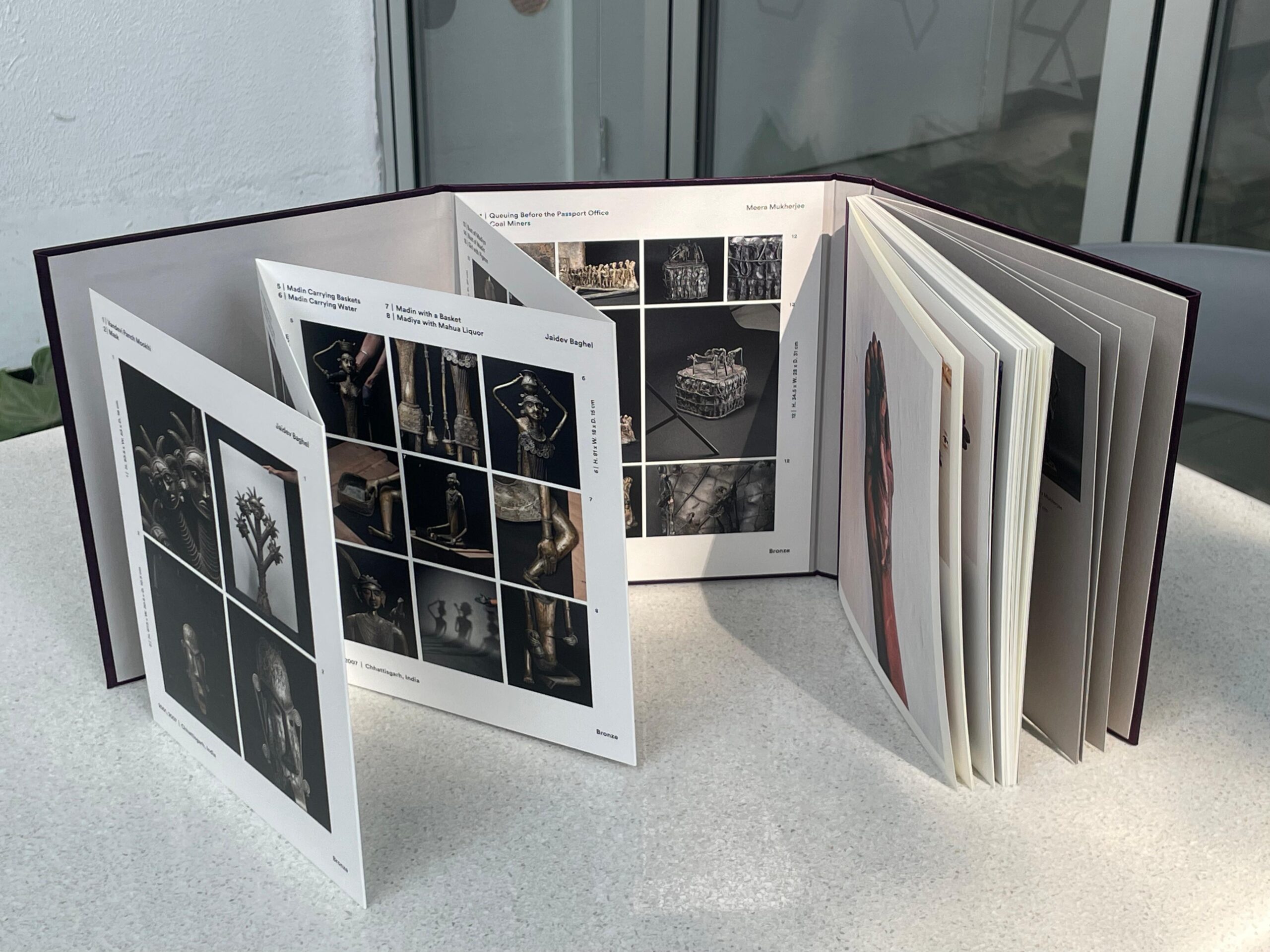

While the exhibition platforms and places the work of these two modernist sculptors in conversation with each other, the accompanying book to the exhibition invites the spectator behind the scenes to the source of this vocabulary. Through two photographic works, fragments from Meera Mukherjee’s diaries and interviews with Jaidev Baghel peppered through, and a concluding essay by art historian Katherine Hacker, the publication brings us into the parameters of producing and presenting dhokra sculpture.

Photographer Jaisingh Nageswaran’s images welcome us to stroll through Kondagaon in Chhattisgarh, meander through its roads along with school-girls and ladies on their way to the market, sit besides it green fields with old men, peep into courtyards with clothes hung out to dry, watch roosters take off from rooftops and the other rhythms of village life. And within this lively thrumming, we duck into the dhokra workshops, here, Nageswaran draws our eye to the labour needed to produce this work through the hands that craft these sculptures. These images of labouring hands sensitively remind us of the sacrifices and skills needed to produce craft. In perfect contrast, photographer Philippe Calia’s photography of the artwork within the bright lights of the studio setup within the museum storage space, occasionally interrupted by hands and other paraphernalia of documentation, shows the detachment and tension of bringing this living tradition into the exhibition space.

In placing these different texts – from diaries, interviews, monographs, a biography and an essay; and the images – personal essay style accompanied by documentation, together, the publication challenges us to re-look at the tired debate between the modern and the traditional. It shows us this distancing is helpful, only so far as it is fruitful to both categories. In allowing for the tensions and the tussles between these two spheres to play out, the result is a treat for the senses. Mukherjee and Baghel tackled simple themes, forged practices that didn’t just highlight their individual achievements but also spoke to their community ties. And much like the title of this exhibition, one isn’t ever sure if the influences were from in, or from the outside. But innovators will always find a way to make art.