Essays

Pyaasa: Unraveling the Poet’s Melancholia in Post Colonial India

Dinesh Khemani

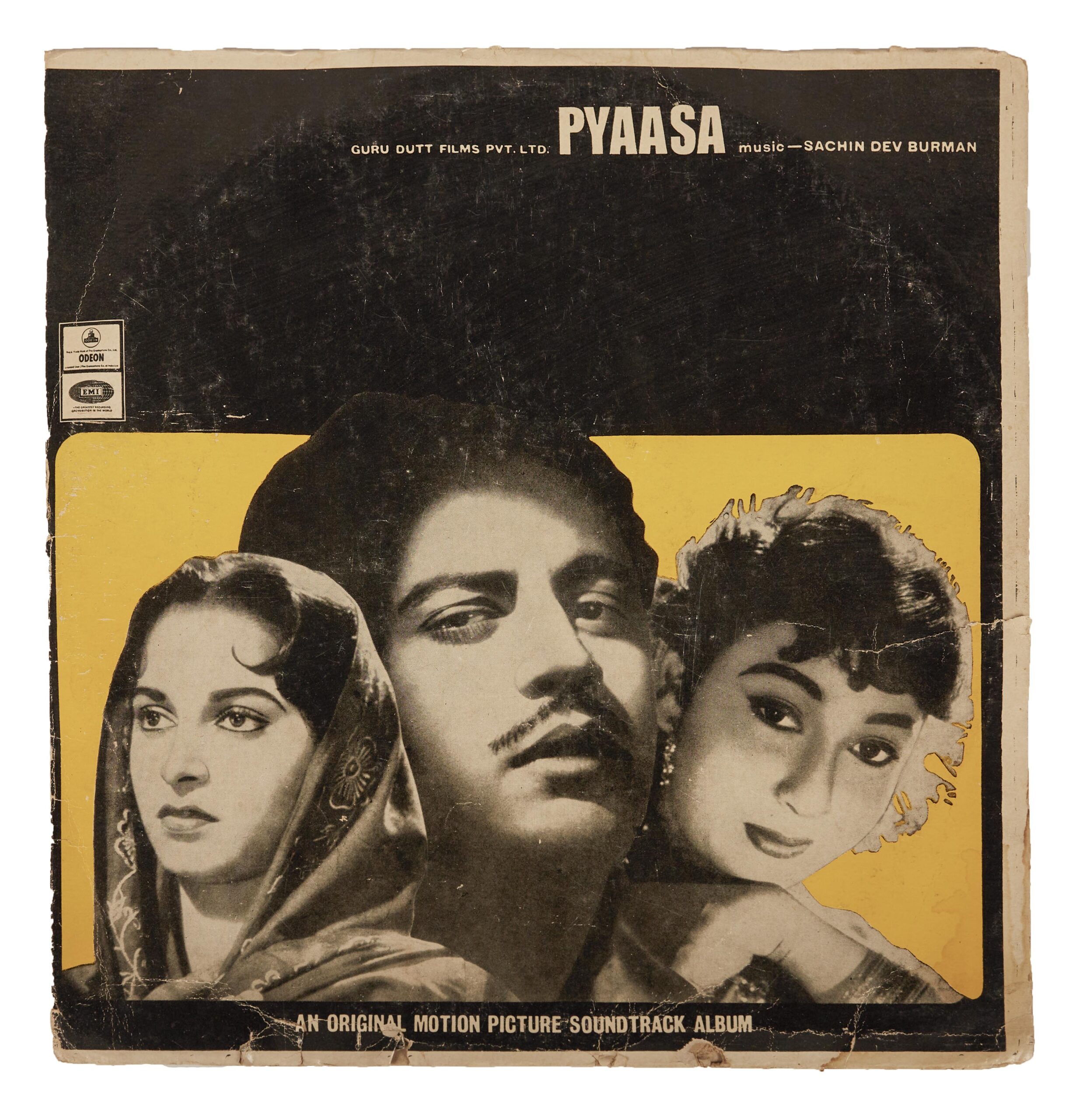

This article by MAP’s Dinesh Khemani, explores the cinematic vision of Guru Dutt complemented by the soul stirring poetry of Sahir Ludhianvi and the starkly expressionist aesthetic approach of the ace cinematographer V.K. Murthy. The artistic sensibilities of these three artists converge in Pyaasa to construct a melancholic and tragic image of the artist and his environment in a post colonial context.

***

Night will pass,

the sun,

will rise,

the lotus will bloom. Dreamt the beetle

trapped inside. Alas!

An elephant

uprooted it, killing the beetle and the dream

This popular verse from Sanskrit literature encapsulates the central philosophical worldview in the film Pyaasa. This film tells the story of a world beset by abject materialism and profit mongering individuals trampling the poetic vision of an artist. The role of the artist pitted against the society is embodied by the vagrant and disillusioned poet, Vijay, played by the charismatic actor-director Guru Dutt. The film is a testament of a world becoming indifferent, cruel, vile, selfish, profiteering and the artist’s lament against that. It is in essence a very unconventional theme explored in Hindi cinema- the plight of the artist in the modern world, with the city becoming the site of this corrupt and immoral reflection.

Pyaasa’s carefully structured melodramatic plot very subtly connects the anguish felt by Vijay to the post colonial issues: for instance, a babu* played by Tulsi Chakraborty (a famous comedian in Bengali cinema noted for his work in Saytajit Ray’s films), remarks the state of affairs in the country where educated men are compelled to work as labourers after slipping him a counterfeit coin.

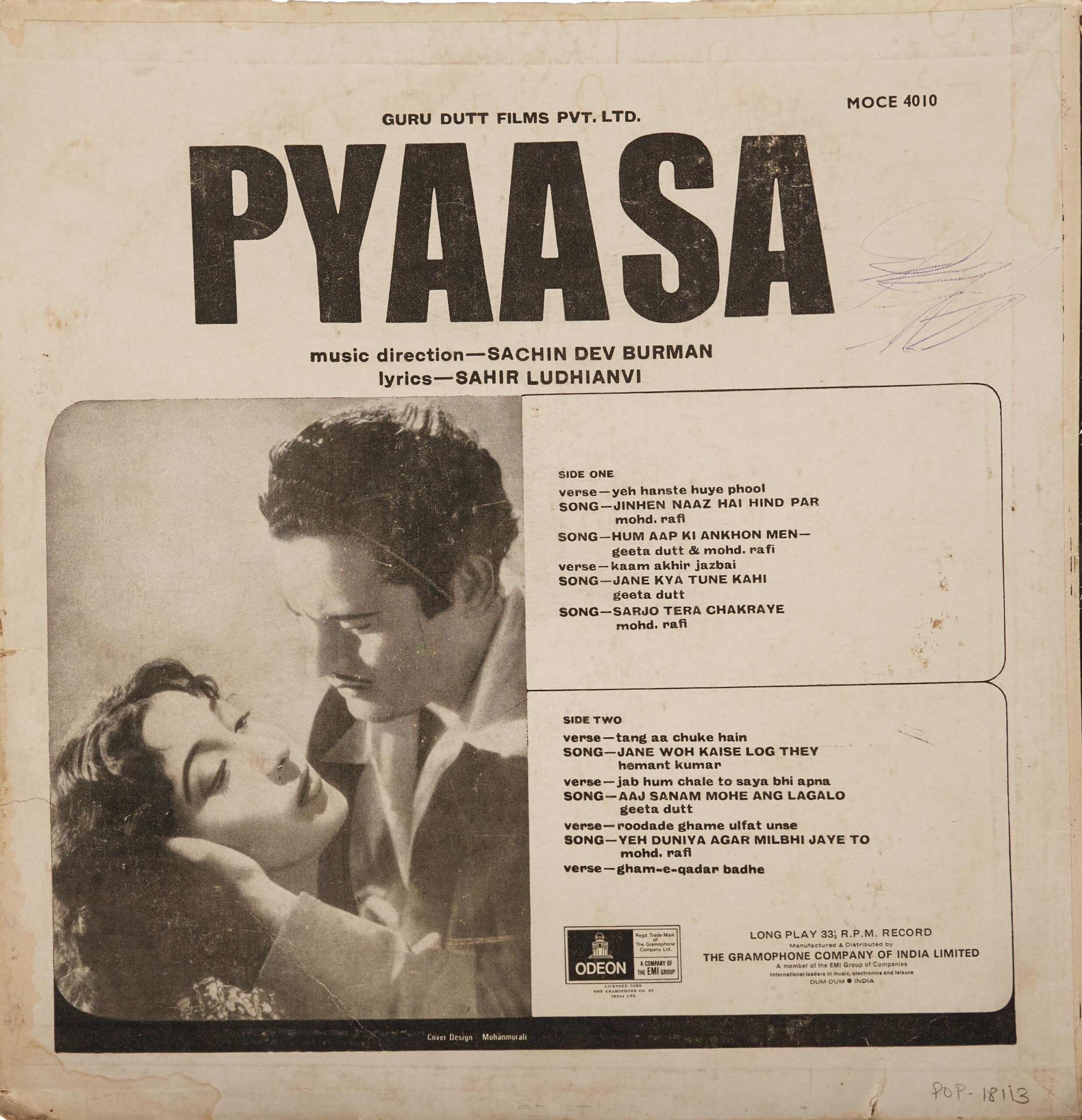

The film’s songs advance the narrative structure with the spoken nazm* penned by the iconoclast Sahir Ludhianvi’s soul stirring lyrics. The visual poetry is complemented by expressionist aesthetic tones deployed by the legendary cinematographer, V. K. Murthy. The film has powerful music, poignant lyrics, memorable melodies and stark picturisation of songs edited to a rhythmic pattern. The songs capture Vijay’s angst against the world fraught with violence, apathy and exploitation in the form of a nazm. With a close examination of the songs one can sense the wider array of themes explored in the film at the time of the post-independence Nehruvian era.

The film’s prologue shows Vijay lying on a grass humming the romantic Yeh Hanste hue phool(These smiling flowers), looking at a bee thirsty for the nectar, like a lover desiring beauty, until it is trampled upon by a passerby. Professor Emerita of Indian Cultures and Cinema at SOAS (University of London), Rachel Dwyer, notes, “Vijay asks what he can add to this beauty and walks away, setting up some of the film’s key themes of what poetry can do in this world of beauty where love is not valued.”

The prologue foreshadows the central theme of the film – beauty, passion, sensitivity and art against the perils of materialism. The film deals with the commercialisation of art, in this case literature raising the question of who determines the status of poetry and role of the artist in the society. In the film, the publishers decide the quality of a work based on its saleability and mass appeal and therefore fail to see any value in Vijay’s nazm. They mock Vijay for expressing his woes about unemployment and poverty through his poetry.

Pyaasa’s songs are a protest against a parasitical, unethical and inhumane way of being in the world, one where human worth is reduced to its market value. In another scene, Vijay, distraught on hearing his mother’s demise, takes refuge in excessive drinking at a brothel where he despairingly watches a dancing girl forced to entertain the lousy drunks, while her child is crying for help. He expresses this suffering through the song Jinhe naaz hai Hind par (Those who claim to be proud of India) and prods the leaders of the nation to walk the streets and bylanes of India, a marketplace for exploitation of women’s bodies. As Rachel Dywer notes, “His reaction to the corruption and degradation around him is moral disgust rather than political; he shows his romantic, ineffectual response to the world that surrounds him by producing beautiful lyrics, the problem that he set himself in the first poem of the film, Yeh Hanste Hue Phool.”

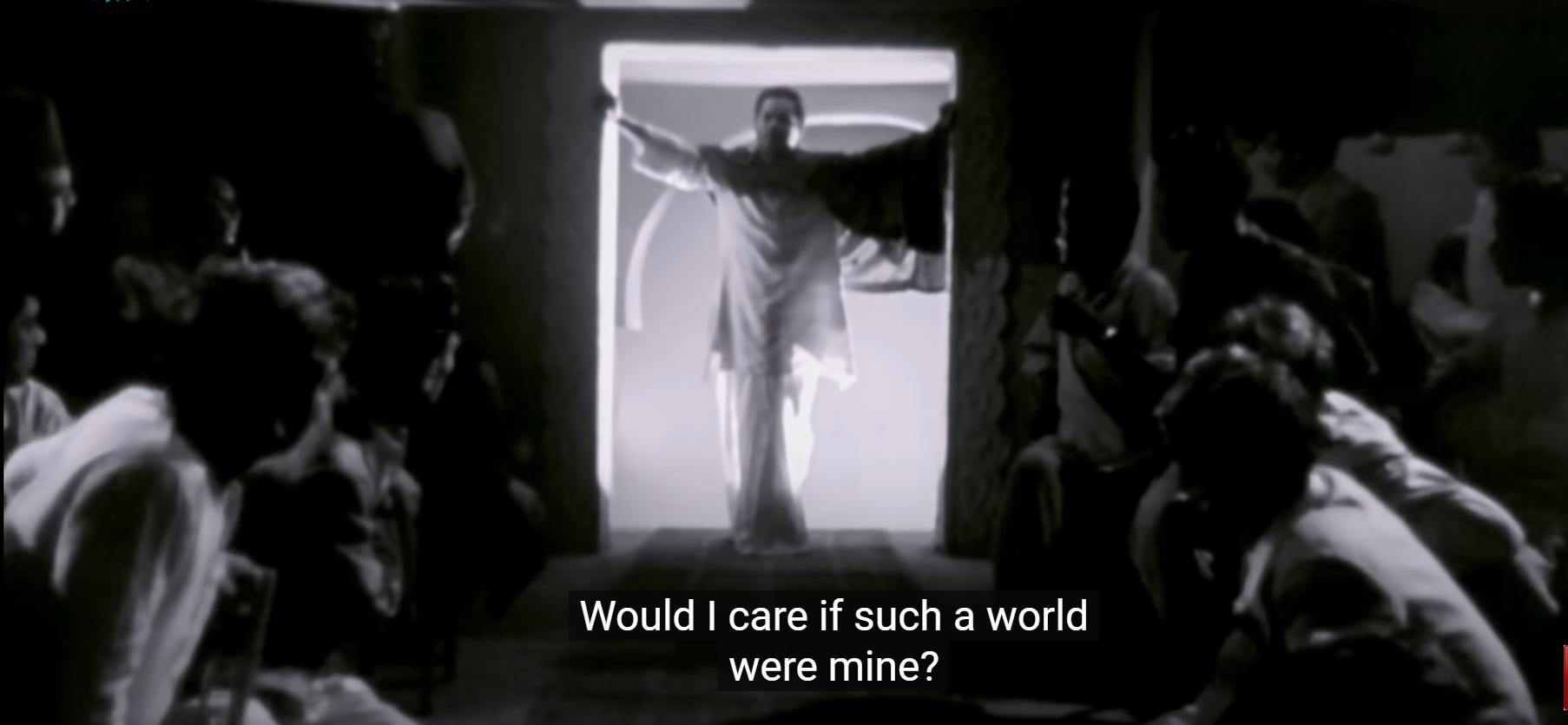

The film ends with the iconic song Yeh Duniya Agar Mil bhi Jaaye toh Kya Hai (For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul) with Vijay arriving for his memorial ceremony and denouncing the world. The song culminates into an outcry against the duplicitous and corrupt society and ends with a clarion call for burning the world down. The film uses Christian imagery, especially in this song. The image of Vijay standing at the edge of the door in the hall (a ceremony celebrating the supposedly dead poet Vijay’s work) against the backlight, with his arms spread out. It is reminiscent of a Christ being resurrected from the dead. Rachel Dwyer observes, ‘Meena reads the tellingly named Life magazine which has an image of Christ on the cover, and when Vijay is presumed to be dead, he seems to be resurrected. He finds his brothers disown him as Peter denies Jesus (Matthew 26:69-75).

The extraordinary performance of the song and the desire to burn the world is also Biblical:

Jalaa doh issey, phoonk daalo yeh duniya

Mere saamne se hata lo yeh duniya

Tumhari hai tum hi sambhalo yeh duniya

Yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaye toh kya hai

The aesthetic tone of the film Pyaasa with its stark use of light and darkness, its melodious tracking in and out during song sequences and edited rhythmically to the S.D. Burman’s legendary music composition and Mohammed Rafi’s voice is worth exploring. The visual mood of the film Pyaasa with its chiaroscuro lighting, inspired by the film-noir genre* was very popular in Hollywood in the 1940s and 50s. A scene mentioned earlier about Meena reading the Life Magazine with the devious publisher Mr. Ghosh sitting at the other side of the dining table alludes to the breakfast scene between the quarrelling couple in Citizen Kane (1941) by Orson Welles. Yaseer Usman in his biography on Guru Dutt titled ‘Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story’ writes, ‘Prof. Ira Bhaskar, the Dean of School of Arts and Aesthetics at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi says that he was influenced by Hollywood melodramatist Douglas Sirk. Sirk produced highly stylised melodramas. His films had strong women characters. Sirk wrote, directed and acted in his movies and was critical of society and capitalism. Citizen Kane was a huge influence on Guru Dutt and so was the drama of Orsen Welles, the influence of German expressionist cinema, and the entire noir tradition. But equally, and this is not emphasised enough, Guru Dutt was deeply influenced by Indian traditions and Bhakti poetry. Guru Dutt’s inspiration also came from 1940s Indian cinema, it’s not one or two directors but the Bengali and Bombay cinema of the 1940s. People like P.C. Barua and later Gyaan Mukherjee, who were his mentors.

Pyaasa along with Kaagaz ke Phool (1959) is known for its expressionist mise-en-scène*. The multiplane compositions in depth, accompanied by evocative lighting and camera movement, often capturing the melancholic mood of the film were some of the inventive aesthetic achievements of the duo – V. K Murthy and director Guru Dutt. The narrative embeddedness of songs is another important element in the film as the poet expresses his angst through the songs written by Sahir Ludhianvi. V. K. Murthy spoke about Guru Dutt’s method of working on the film set in the book Guru Dutt: A Life in Cinema by Nasreen Muni Kabir, ‘Those scenes were very well conceived, but they were mostly on-the-spot decisions. It’s the Indian method of working. We constructed the sets all right, but we conceived the shot on the set. We would both discuss where to place the camera. Guru Dutt had a tendency to do things extempore; because whatever he had planned earlier would be changed. Many things were changed. We worked with a general outline of scenes, no details. We’d go on the set, and if he didn’t find it to his liking, he’d say, ‘Okay, cancel it’! Suppose we shot a scene, and he didn’t find the effect he wanted, he’d say, ‘Scrap it. We’ll do it again.’ Actually he has redone many scenes, shooting and reshooting; this is particularly true of the way he worked in Pyaasa. Before Pyaasa, he would scrap only one or two shots of a film, rather than whole sequences. People appreciate his films today, but they were not the result of quick decisions, or confidence.’

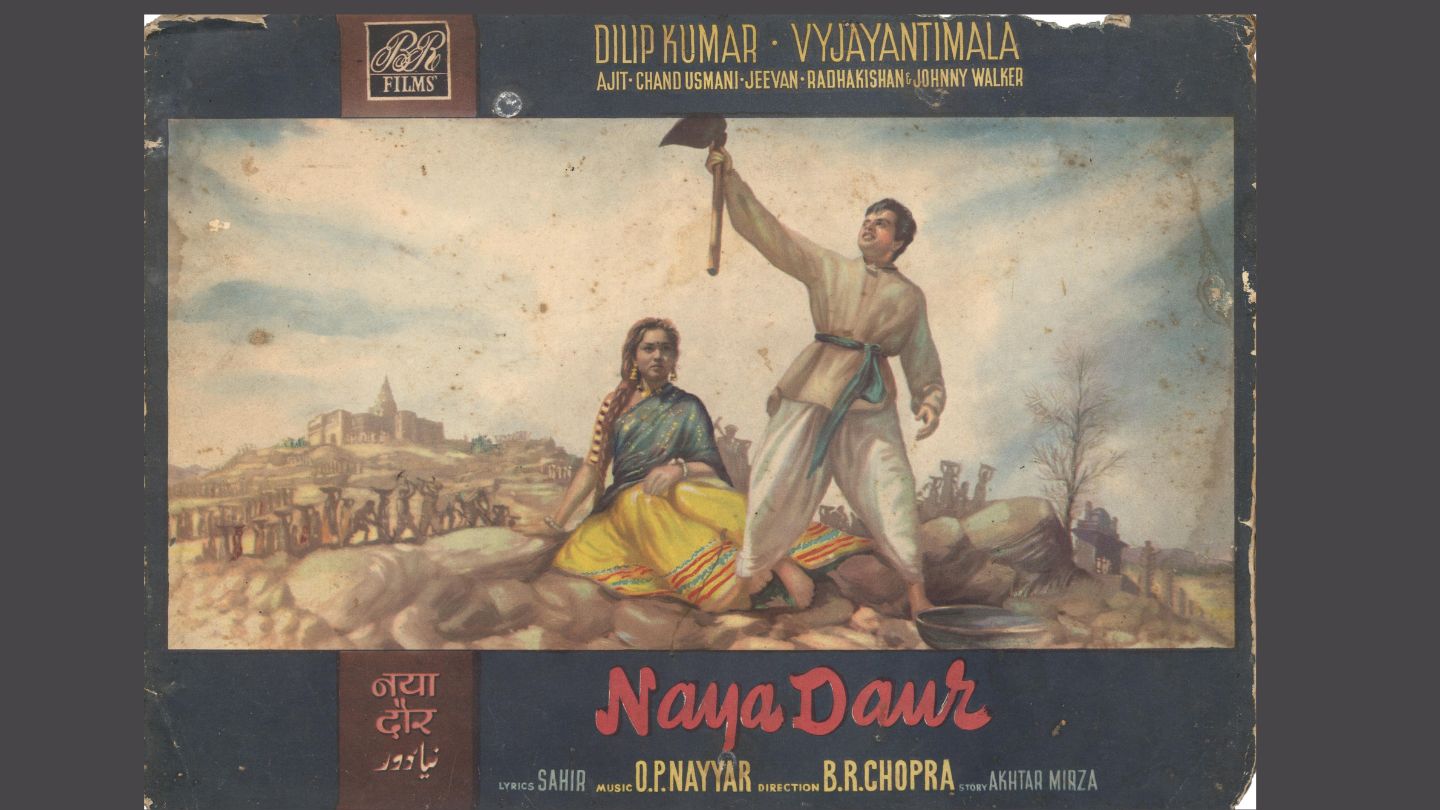

Pyaasa was released in the same year as Mother India celebrated for its nationalistic spirit, and B. R. Chopra’s Naya Daur that welcomed the idea of the Nehruvian vision of nationhood with Gandhian principles. The film’s ideological position seems more complex than the other two celebrated films of the year. Pyaasa was more bleak and cynical in its message, seen through the eyes of the tragic and disillusioned poet Vijay ten years after India’s independence. The film doesn’t directly engage with overtly political or social issues but presents the audience with a reflection of the human condition. A critique of society and the role of the artist in an burgeoning age of crass commercialisation and lamented the absence of fundamental human values. The beauty one sees in the film is a culmination of various artists’ sensibilities – the heart wrenching songs penned by Sahir Ludhianvi, the variegated musical compositions by S. D. Burman backed by Mohammed Rafi’s sonorous vocals, and lastly V. K. Murthy’s ability to render Guru Dutt’s melancholic and romantic vision through the visual poetry in cinematography.

Notes:

Babu is a title given during the British Era to the emerging middle class working in the colonial administration as clerks. Since the mid 20th century the term has been used pejoratively to describe people working in the Indian Administrative Services and other government officials.

Nazm is an important genre of Urdu and Sindhi poetry written in rhymed verse but also in prose style in modern times.

Film-noir literally meaning film black was a genre dealing mostly with crime and detective stories that emerged in Hollywood roughly around the 1940s to 50s. It mostly featured stories unfolding in urban spaces at night with stylised and moody lighting, cynical heroes, expressionist visual composition and femme-fatale- a glamorous young seductress who will entrap the male protagonist for ulterior motives, leading to their annihilation. To read more on this visit- https://www.umontanamediaarts.com/MART101L/characteristics-of-film-noir

Mise-en-scène is a French term that literally translates to placing on stage. Though the term was originally applied to theatre, it has been applied to cinema to mean everything that is arranged in front of the camera- sets, actors, costumes, hair, makeup, composition and how scenes are arranged. It allows directors to implement their aesthetic approach and each director would have a different approach to Mise-en-scène.

References:

Open The Magazine. “Thirst for Change – Open The Magazine,” August 10, 2016. https://openthemagazine.com/essay/thirst-for-change/

Indian Cinema – The University of Iowa. “Pyaasa,” n.d. https://indiancinema.sites.uiowa.edu/pyaasa

Kabir, Nasreen Munni. Guru Dutt: A Life in Cinema, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1604/9780195638493.

Usman, Yasser. Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story: An Unfinished Story, 2021.

***

Dinesh Khemani works as a Project Lead and Senior Researcher for the digitisation project at MAP. In his free time, he likes to catch up on reading, explore filmmaking and art.