Essays

Experiencing Photography

Jyoti Bhatt

Celebrated Indian artist, Jyoti Bhatt speaks of his journey as a photographer.

I came face to face with a camera for the first time when I was one years old. I can say this because I have seen a photograph of myself in an album that my father had made of our family. However, it wasn’t until I was about nine that I became aware of the camera. As a youngster my friends and I played with a kind of fantasised camera made from an empty matchbox. We filled it with images cut from newspapers and magazines and pulled out each one at a time, while mimicking a clicking sound. Sometimes we pasted inside the matchbox a round mirror called an ‘aabhlu’, used in Saurashtra embroidery, and we would open the box to show the ‘photographed’ person their (reflected) image. Alternatively, we also played with another imaginary camera conjured by crisscrossing our fingers.

I joined a special art class in my school when I was eleven. Unlike in most schools at the time, the art teacher was a practicing artist. He was very enthusiastic and shared his thoughts with his pupils as if they were his artist friends. Though like many others, he misinterpreted Gandhiji’s thoughts about machines.He seemed to believe that a photograph was an inferior form of art because, and I quote, ‘it was produced by a machine’. He went on to express that ‘unlike a painting,it did not emerge from an artist’s heart and was not made by his own hand’. This idea did not appeal to me much. My father was a self made mechanical engineer.Machines, according to him, were only sophisticated forms of tools. On the other hand, the motifs of a ‘Jantar’ (machine) and a ‘Pavan Charkho’ (wind gadget)were used metaphorically for a human body in some traditional devotional songs that I liked.Photography had become very popular within the seven decades of its invention. László Moholy-Nagy,the painter, photographer and teacher from the Bauhaus in Germany, said ‘the illiterate of tomorrow will be the one who can’t use a camera’. It may not be wrong to say that Nagy’s prophecy has been proven true, even in India. The term ‘photo’ has long been included in the official Gujarati dictionary. A large number of Indians use this term without any idea that it is a word from a foreign language.

It was during the last years of my schooling that I became aware of what I knew to be a ‘foto’ was actually spelt ‘photo’ and that it was incorrect to call a framed oleograph by Raja Ravi Varma or other similar lithographic reproductions found on the walls of most Hindu homes a “photo” of this God or that Goddess. After my schooling, I studied painting from 1950 to 1959 at the MS University of Baroda.

As part of the academic training I had to make portraits and sketches of people occupied in various activities, including theirparaphernalia and costumes. Such pencil or colour studies also bore some kind ofsimilarity with photographs. However, I was unable to attain the lively, tale-telling expressions of the people portrayed. Eventually I started appreciating the difference between a photograph and a drawing and their unique qualities. I was happy to realise that contrary to the famous lamentation by the French painter Delaroche, when he proclaimed upon seeing the Daguerreotype, ‘From today, painting is dead’. The camera had in fact contributed much to the continuous development of painting just as much as they have contributed to photography.

I got my first camera, a Voiglander, in 1957. Initially I used it merely to take pictures of my paintings and the works of my fellow artist friends. However, it soon replaced the pencil and I started using it for making visual notes. I realised that the camera recorded so many details that at times I had opted to ignore and more often had failed to notice. What I found most fascinating was the fact that a camera could record so accurately and objectively in just a tiny fraction of a second.

We know from the Mahabharata that Arjuna was taught to focus only on the eye of the bird, and not all those who were engaged in the archery contest; not the tree, not any branch, nor the bird itself. However, I realised that to make a photograph more eloquent, one must be attentive to a single point of focus, but also develop the ability to focus attention on that which surrounds the main ‘subject’, and have a grasp of its contextual significance with on-going events.

Inspired by paintings of some Spanish and Italian artists during the early 60s, I was preoccupied with tactile and visual qualities of various materials and surfaces, and shapes of marks on them that reminded me of something else – an object, place, etc. It was difficultto bring out such features in my pencil studies even with accompanying written notes, but the camera could capture all the nuances of their visual attributes accurately. Soon, I began to photograph surfaces I found at various places, as though they were images painted by nature. Although I no longer make paintings with such a visual language, I do not let any opportunity go of photographing surfaces that suggest some metaphorical meanings or identifiable forms, which evoke emotional responses. While there is not any apparent qualitative relation, such images remind me of ‘Equivalents’ -the generic term Alfred Stieglitz had coined for some of his photographs.

Between 1964 and 1966, I studied printmaking at the Pratt Institute in New York. While in the USA, I ha the opportunity of seeing some excellent photograph exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and variou other museums. Without hesitation, I would name ‘Family of Man’ as the most important and influential show of photographs that I have ever seen. Edwar Steichen curated the MoMA exhibition during the 1950s and it toured all over the world. Many others have emulated its concept and methodology. I too adopted its blueprint on smaller scale during the few photography exhibitions I was involved in organising.

In 1967 Bhupen Khakhar, Gulam Mohammad Sheikh and I were asked to find what is representative of folk art from Gujarat for seminar on folklore that was to be held in Mumbai. I illustrated the contextual reference of these forms, photographing them in their original locations with the people who made and used them. The objects and photographs were then displayed during th seminar However while travelling to assimilate the collection, I had noticed that most of the traditional forms and visual expressions that I had seen at several places during the pre-independence days were in decline and some did not even exist anymore. It was obvious tha due to various factors related to progress in the direction of industrialisation and westernisation, many of our cultural traditions ha suffered the consequence of utter disregard. They were not to survive long in their original forms and environment. These consequences seemed inevitable, regardless of what seemed right or wrong for me.

There was nothing I could do about my concern for preservation, but I continued making photographic records of the art forms an art traditions that were still alive. This was in keeping with the ideas of Professor

K.G. Subramanyan, who had coined the term ‘Living Traditions’. At the time, my wife Jyotsna and I were teaching at the M. S University. Our jobs provided me with the essential monetary resources for materials and travelling, but I could only travel during vacations or on leave of absence from my job. The limited resources of time and money made it imperative to restrict my focus only on a few themes and subjects. I thought ritualistic and secular art forms, usually created by women using transient materials such a clay, dung, flowers, rice flour, etc. needed to be given priority. Such forms were not considered important as ‘National Cultural Treasures’ or ‘Archaeological Heritage’ and their deteriorating condition did not seem to be bothering the Government authorities.

Finding appropriate raw film was very difficult during those pre-globalisation days. I had learnt the basics using black and white fil and working in a darkroom. I knew that colour film had a limited life span, especially in our hot and humid climate, but it could record information that was impossible to capture with monochrome film. So I tried to photograph the art forms with both kinds o films and I am happy I had taken that decision. Most of the colour transparencies are now discoloured and have become layered with fungus, beyond repair. However the images that were recorded in black and white film have survived.

Soon after I started photographing traditional art forms, I was very fortunate to have the company of my artist friend Bhupendra Karia. He had returned from the USA to work on his pilot project of documenting our varied cultural aspects. Another friend joined us, the sculptor Raghav Kaneria, who shared my interest and concern for folk and tribal art forms of India. He had returned from th U and had started teaching at MS University of Baroda. Bhupendra was a friend, philosopher and guide for both Kaneria and myself He went back to the USA after three years, but Kaneria and I went on pursuing our photo documentation, which continued for almos twenty five years, both collectively and individually. We recorded as many forms and their variations as we could find. We also visite some places repeatedly to observe and record changes to those forms. We also tried to record the essential steps in the process maki such art forms and their relationship to the lifestyles of those who made them and lived with them. Unfortunately video was not yet a integrated part of still cameras, as it is now and we could not afford the large video cameras available at the time.

Nietzsche once said, ‘experiencing anything as “beautiful” meant experiencing it necessarily wrong’. I agree with this thought, but only in principle. In practice, I have followed the first of the two main aims of Lewis Hine, ‘If beautiful it should be preserved and if hideous it should not be tolerated’.

I hardly made any paintings while I concentrated on printmaking, and then could only make a few prints during the years we photographed the art forms. So, from a painter and then a printmaker I had acquired the third label, ‘a documentary photographer’. While looking back, I wonder if I can aptly be called any of these.

Other than music and cinema, what I have enjoyed most so far is seeing and making visual images – mainly of two-dimensional kinds. My interest in visual images allows possibilities in conjoining painting, print-making and photography. The three mediums, in which I have worked on and off, seem to have made their mutual impact on my imageries. My photographic images often look like intaglio prints and several of my prints have been based on my photographs and paintings.

I did not have any formal training in photography, however, the late photographer Kishor Parekh and I were friends from our childhood days. His friends, Raghu Rai, Raghubir Singh, and their friends, gradually became my friends. I travelled with a few of them and Dr. Stephen Huylar, an anthropologist, writer and photographer from the USA, which gave me the benefit of observing their working methods and discussing the potentials of photography as a visual language. My artist friend J. Swaminathan was heading the Rupankar Museum of Fine Art, Bharat Bhavan, in Bhopal during the !”(&s. He provided me opportunities of travelling in some remote tribal regions of Madhya Pradesh. The wholehearted encouragement and guidance from my gurus, Prof. Sankho Chaudhuri and Prof. KG Subramanyan gave direction to my work.

By the 1960s, artists from all over the world had become interested in the attributes of the visual image(s) made with different mediums including a camera, and also the emotions and meanings they evoked. Many famous photographers had their initial training as painters and many painters were using photographic images in their creations. Questions such as ‘Is photography art?’ were resolved or had become out of fashion in the European and American countries, but in India, art authorities remained clinging to the ideas similar to our ‘caste system’. The Lalit Kala Akademi, India’s National Academy for Visual Arts, refused to show photographs in its annual shows. Graphic Prints such as etchings, lithography and serigraphy were also rejected if they incorporated any technique related to photography. Paradoxically, the Akademi had to accept and exhibit the photographic images sent by other countries during its International Art Triennials.

Seven painters from Baroda, including myself, held a show in 1969 entitled ‘Painters with a Camera’ in Jehangir Art Gallery, Mumbai. All the works shown in the exhibition were initially shot with cameras and then made in a darkroom with the equipment and chemistry of photography. Though the works were not great photographs, it showcased painters who accepted the camera as a potential tool for their expression.

For my entry in the ‘Graphic Art’ section of the Annual Art Exhibition of Lalit Kala Akademi in !”$!, I had submitted one of the high contrast, black and white prints I showed in our previous Mumbai show. The work was titled ‘A Face’, with ‘silver gelatin print’ being the appropriate technical term, which I mentioned as the medium to this photographic image. I was pleased to learn that my print was selected by the jury members. This could not have happened if they had associated the term ‘silver gelatin print’ to a photograph. I am happy that the attitude towards photography in our galleries and academies has started showing a marked change. Some photographic images were accepted and even awarded during the last few National Art Annuals. However, there is still a long way to go.

My first solo exhibition of photographs was organised at Art Heritage Gallery in 1984/85. The same images were then shown in Cymroza Art Gallery in Mumbai that same year and I found it most interesting to observe how viewers reacted to my works. People who liked my paintings and graphic prints were disappointed to see small, black and white photographs and those who anticipated seeing ‘pure photography’ were dissatisfied with my small images that looked like graphic prints, made by a painter. One of the biggest complements for those small black and white prints was by one young Bengali gallery attendant. His duty required him to sit near the gallery entrance from morning until evening and open doors for the visitors throughout the show. In mixed Hindi and Bengali he said, ‘I have seen many shows of large paintings that remind me of posters. Their appeal hits you between the eyes at first sight. But Dada, your photographs are different! Like “Rojani Gondha” (Tube Rose), they keep on blossoming every day with “Nooton Shugondh” (fragrance)’. I had felt hugely pleased, but also a bit envious because he could see in my work the layers of meanings that I had not seen myself. Later I came to know that the American photographer Minor White used to ask his students to sit on the floor for three hours while each of them would have to keep looking at a photograph on the facing wall. This ritual-like exercise sharpened his students’ perception and ability to see beyond the surface to comprehend layers of subtle, implied meanings of an image.

Raghav Kaneria and I continued working on our self-appointed project and together exhibited our works. Photographing in rural and tribal regions was never easy and it required us to take some risks and my respect for photographers continued to expand. While painting Guernica and War and Peace, I do not think Picasso had to face the kind of physical danger that photographers such as Lewis Hine, Robert Capa, W. Eugene Smith, and their likes had encountered while pursuing their work on battle fields, in jungles and amidst the industrial world. There are many others who have contributed to my understanding of the form and meaning of photography and its visual vocabulary. I tried to learn from their works, but continued with what I had chosen to pursue and considered more urgent.

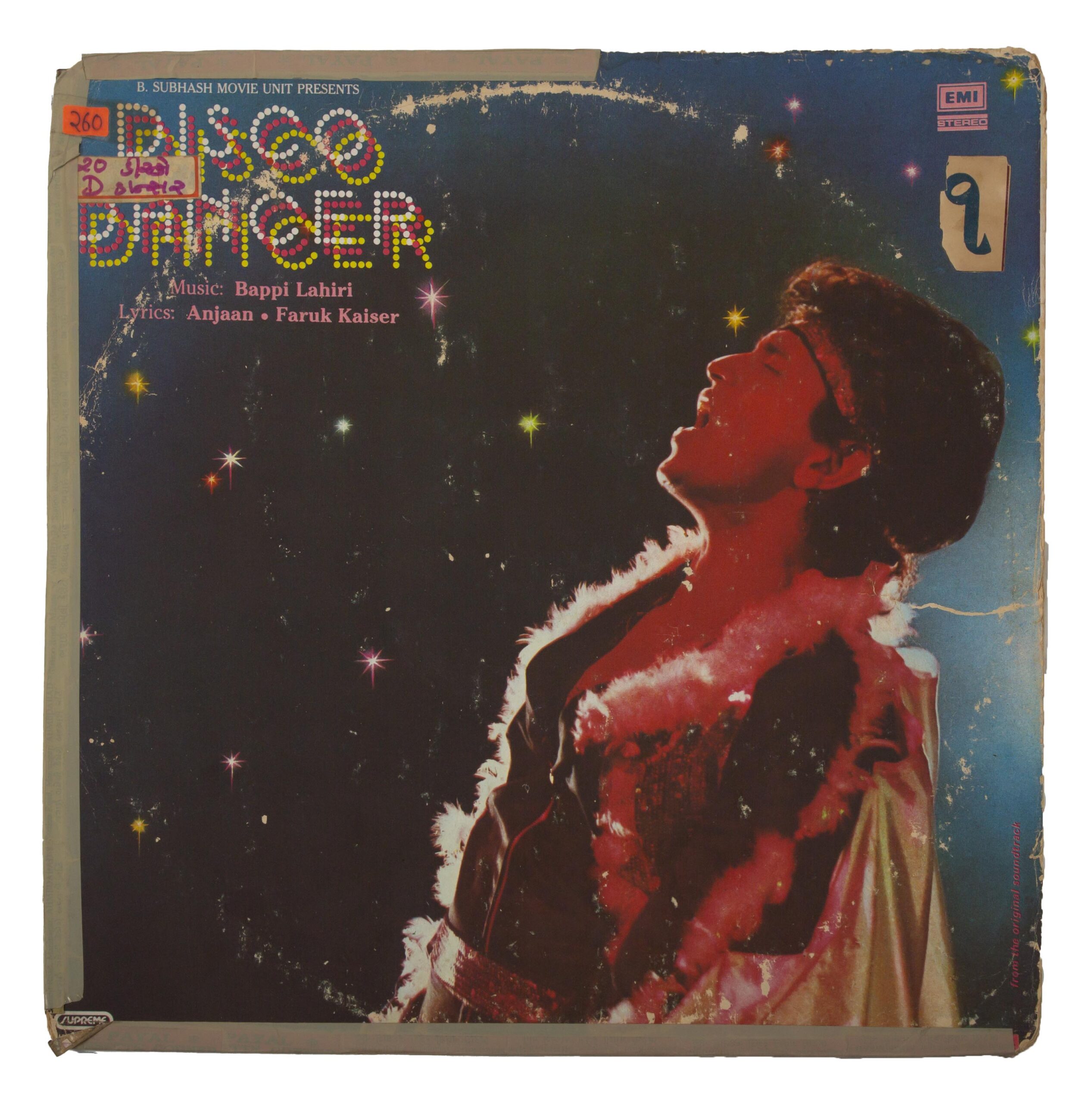

I have attended many seminars related to photography over the years and perhaps the favourite cliché among established practitioners is to advise young or emerging enthusiasts to keep from ‘imitating’ the styles of famous photographers. The difference between terms like inspiration and imitation is difficult to define accurately or objectively. An original way of articulation comes to be recognised as a cliché when it is overly used, but it is accepted and repeated by others because of its capability of communicating ideas or concepts expressively. All symbols and proverbs might have been created by some individuals, but they have become an essential part of our life. The term ‘Gandhigiri” used for the first time in the film sequels of Munnabhai is now even used by many, including some genuine followers of Gandhiji. Similarly, sometimes photographers use such proven forms of visual expressions. The lighting style named after Rembrandt has had a large number of its followers among photographers, but it also encouraged many to explore new ways of lighting and the emotional responses they evoke among the viewers of paintings, photographs, plays, and films.

There are several images that I shot during the early years of my journeys, but had not cared for printing them. It was only after having seen photographs by August Sander, Cartier-Bresson, and Raghu Rai, that were similar in subject matter though not in quality, I started appreciating some particular photographs I had taken. I have photographed bicycles in various places and in odd situations. For me, their value as expressive images increased after seeing the images of bicycles in Ashwin Mehta’s book. Such similarities not only make me aware of the weakness and faults of my own work, but also help me to understand the finer quality of the works of the masters. It became necessary for me to more or less stop photographing after the mid 1990s. I work on and off with my old images and try to give them a rejuvenated avatar on a computer with the help of young artist friends. I was very happy as a painter when acrylic paints became available – it offered advantages similar to watercolours and oil paints. Similarly, making images on a computer screen allows me to perform darkroom tasks in bright light, without straining my ailing eyes on minute details. It is possible to maintain the visual characters of photographic prints, but I allow my painter and printmaker self to indulge freely and keep away from one more label; namely a purist.