Blogs

Dreamscapes: Arpita Singh

Shubhasree Purkayastha

Born in pre-Independent India, in pre-partition West Bengal, Arpita Singh ranks among India’s most prominent contemporary artists. For an artist not given to complex explanations of her own art, Singh’s paintings are quite complex – both in themes and in colour palettes.

“In life, both memory and forgetfulness are very important things. That something that was about to happen, didn’t in fact come to be, or stopped or came to an end. You’re trying to recall something, You know what it is, but you’re unable to completely grasp it. There is no greater tragedy than this.”

Born in pre-Independent India, in pre-partition West Bengal, Arpita Singh ranks among India’s most prominent contemporary artists. Moving to Delhi in the late 1950s, she armed herself with a diploma in Fine Arts from the Delhi Polytechnic and was trained under artists like Jaya Appaswamy, B.C. Sanyal and Biren De, among others. From there, she moved on to take up a job as a textile designer at the Weavers Service Centres in Kolkata and New Delhi, where her interaction with artisans and learning of traditional techniques (such as kantha embroidery) greatly influenced the development of her artistic style.

Untitled, 1986, Arpita Singh, Oil on canvas

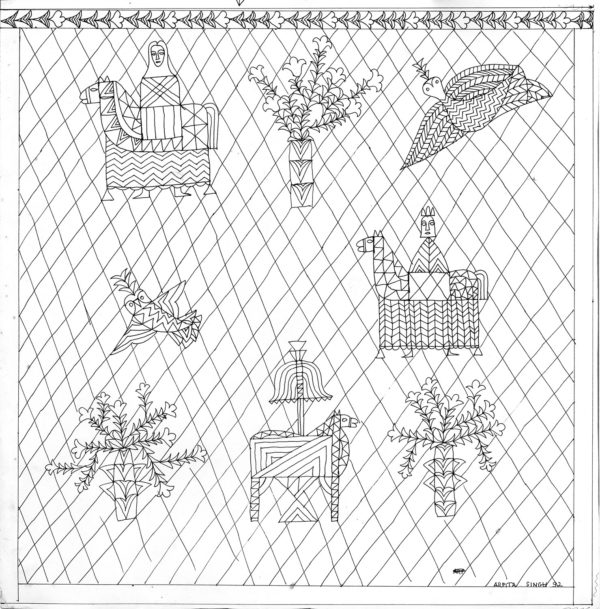

Untitled, Arpita Singh, 1992 Pen and ink on paper

“In the technique or effect of my work, some things are visible and some are not. Some things that were coming up are submerged.”

For an artist not given to complex explanations of her own art, Singh’s paintings are quite complex – both in themes and in colour palettes. Her influences may be situated in her experiences with traditional Indian art, an interest in Indian mythology and miniature traditions as well as an intuitive quality that guides her brush.

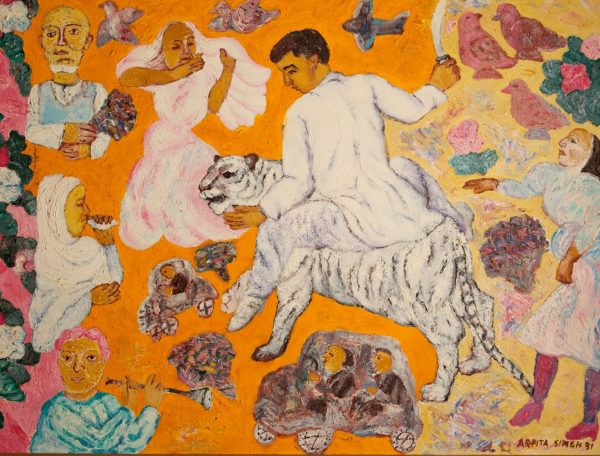

Known for an artistic oeuvre replete with striking characters, emotionally charged portrayals and elaborate forms of storytelling, women-centric narratives are often at the center of Singh’s stories. From sorrow to joy and from suffering to hope, Singh paints emotions and perspectives that every woman in the world might have gone through, as if maintaining a steady and silent communication with each one of them. Her vibrant palette is usually dominated by blues and pinks, and her canvases overflow with energy: featuring a range of figures and animals, as well as objects or motifs such as guns and airplanes.

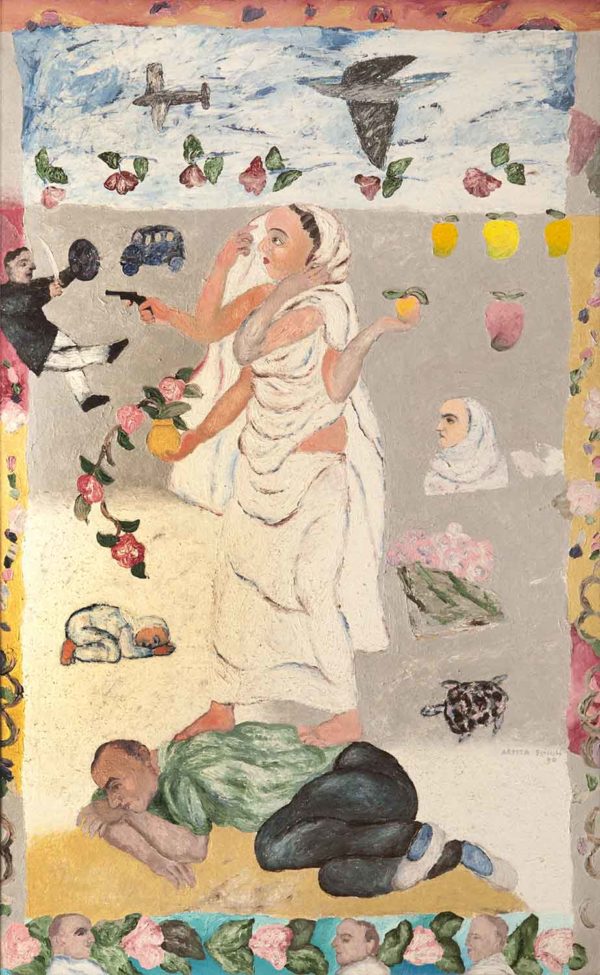

Devi Pistol Wali, Arpita Singh, 1990, Oil on canvas

In a work titled ‘Devi Pistol Wali’ for example, the figure of the woman references the Hindu icon of Durga. This Durga, however, is garbed as a widow, perhaps referring to the war widows that also figure repeatedly in Singh’s works. She holds up a small black revolver, pointing it to a male figure that falls out of the frame. The demon that traditionally Durga tramples upon is swapped here with the figure of a man, while another bows down in front of her in veneration. Singh’s work is often compared to that of French modernist March Chagall – not being overtly feminist or autobiographical, but retaining an allusive dream-like quality featuring free-floating or half-drawn figures.

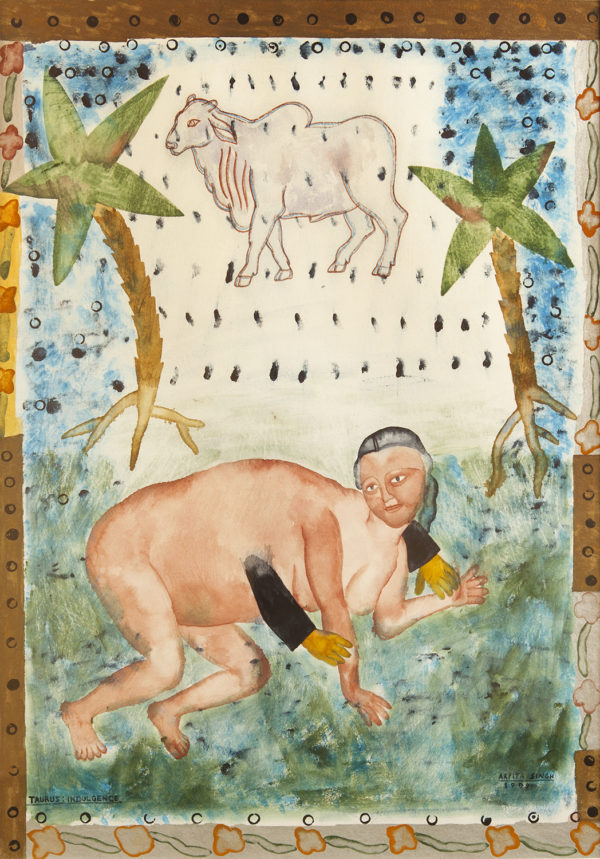

Taurus: Indulgence, Arpita Singh, 1999, Watercolour on paper

“Encountering the blank surface of a canvas or paper fills me with anxiety. It represents a challenge and the first mark I make on it is always exciting.”

In the late 1970s, Singh dabbled with a completely different style of non-figurative art. What many would call abstract paintings today, these canvases are filled only with monochromatic dots and lines – an exercise she engaged in to “go back to the basic elements in order to free up the hand and the mind”. This exercise led to the production of a large number of black-and-white works over a period of six years. Her experiments with the monochromatic were an intense play with lines as they grew into meshes, grids, webs and scaffolds, all morphing together to transform into textured surfaces.

Untitled, Arpita Singh, c.1970, Etching

Untitled, Arpita Singh, 1988, Pastels on paper

“The space makes you discover things. The things you see as you walk along, that you have not seen before. So whatever is being made, that pulls in other forms on its own. It’s isn’t that I have put any special effort into this.”

Shortly after this period of abstraction, Singh found herself painting figures again but this time, another element creeped into her works – the text. In her own words, “I often like to work with a palette knife and I found the edges of the knife formed some kind of letters. I pressed on until whole words emerged and little sentences would come out of a particular arrangement”. In these works where the text and image collide, sometimes they hold together and relate to each other but sometimes they are just visual elements that do not make words. The method again was organic and process oriented, where Singh noted that she would never begin with any pre-decided notion of the words or sentences that she wished to include in the composition.

Lotus Pond, Arpita Singh, 1995 Oil on acrylic sheet

“The female figures in my works are just like any other forms. Each form is important for that particular work to which they belong. I don’t care whether they are frozen in time or part of a larger narrative. They are there because of a certain need. They will vanish when the need is over.”

Singh, along with colleagues like Rameshwar Broota and Jogen Chowdury, was a leading figure in India’s second generation of modernists who came into their own in the 1960s. She was part of an early Delhi-based group called the ‘Unknown’ and had her first exhibition at the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society in the 1970s. Here, she sold only one painting for a mere one hundred rupees, but this exposure led Singh to her first solo exhibition in 1972. This was also a time when she was a female artist in the largely male-dominated art circle of India, and saw herself gravitating towards other female colleagues like Nilima Sheikh, Nalini Malani and Madhvi Parekh, coming together in an informal group of their own.

With over five decades dedicated to the medium of painting, Arpita Singh’s extraordinary body of work represents a tight tapestry of mythology and history. They act as reservoirs of collective memory and culture, while navigating the many complex and often disturbing realities of the world she continues to inhabit.

Man on white tiger with clay bird, Arpita Singh, 1991, Oil on canvas

Couple, Arpita Singh, Watercolour on paper