Blogs

On A Roll!

Shubhasree Purkayastha

Who does not like stories? From the earliest humans drawing mysterious motifs on cave walls to an online video gone viral – we are really just finding ever-innovative ways to create and share stories all the time.

Who does not like stories?

From the earliest humans drawing mysterious motifs on cave walls to an online video gone viral – we are really just finding ever-innovative ways to create and share stories all the time.

Used largely as a means of passing on moral lessons and religious knowledge, the earliest method of storytelling was oral, embodied in the concept of the katha in India and the person of the kathakaar (or the travelling bard).

A unique medium of storytelling—prevalent across the length and breadth of the country—is that of the scroll. From the eastern corners of Bengal to the deserts of Rajasthan and the deep south – the scroll has been a constant companion of itinerant bards who travel from village to village, unrolling them to willing audiences and narrating the stories they hold.

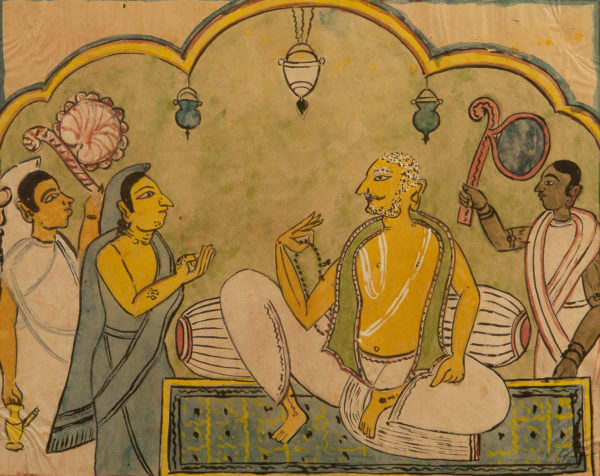

Pata depicting a saint, 20th century, Unknown Maker(s), Gouache on paper

The travelling story

In the Paschim Midnapore district of West Bengal lies the quaint little village of Naya. Otherwise ordinary looking and unexciting, it comes alive once every year when it’s time for the annual pata mela (scroll fair). For the village of Naya is the hub of the patachitra artform of Bengal, and almost every resident here is a patua chitrakar. The patuas are a group of storytellers who move from village to village carrying their story-scrolls and performing in front of an audience through a song composed specifically for that particular pata.

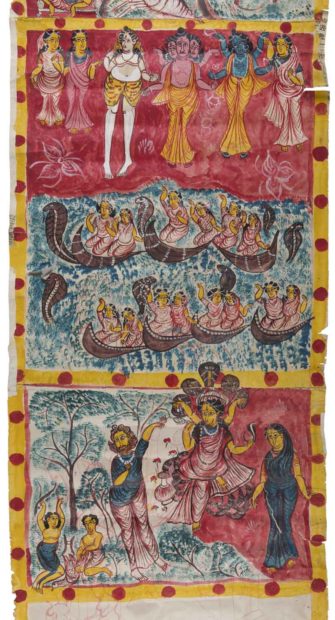

The scrolls themselves are created using paper and fabric, and painted using completely organic colours. Important episodes from the chosen story are painted within registers arranged vertically and the patua rolls out the scroll bit by bit as the story progresses, pointing to the episode they are singing about.

Pata of Manasa Mangal(detail), 20th century, Unknown Maker(s), Natural pigments on paper

Sometime in the 19th century, these patua painters moved to the city of Kolkata looking for better employment opportunities. This migration gave birth to the Kalighat School, an art style known for its distinct flowy brushwork and bold, flat colours that is reminiscent of the patachitra style that these artists were originally trained in.

Shad Bhuj Chaitanya, Late 19th century, Unknown Maker(s), Opaque watercolour on paper

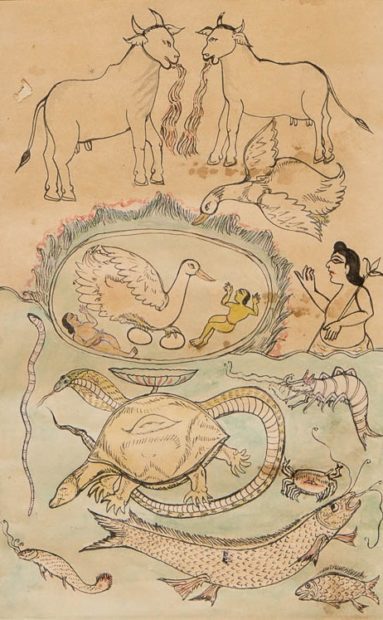

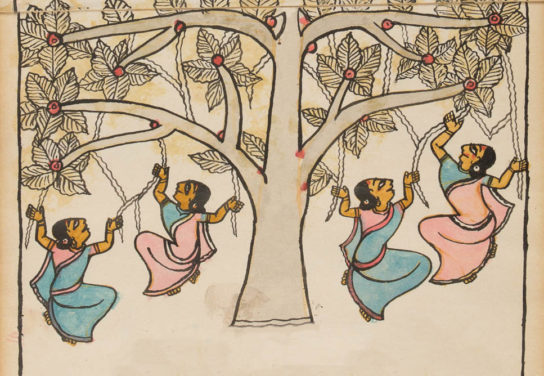

The indigenous Santhal community living in pockets of West Bengal and in the neighbouring states of Orissa, Jharkhand and Bihar have many cultural commonalities with the Bengalis, including the art of the patachitra. While their scrolls borrow the format from the Bengali patuas, the style and subject of the Santhal patas are uniquely their own, focusing more on origin stories that were orally handed down through generations in the community.

Santhal Korom Binti Pata (detail), 20th century, Unknown Maker(s), Natural pigments on paper

The never-ending story

In the deserts of Rajasthan, another ancient storytelling tradition lives on today through the nomadic Rebari community that deems itself the hereditary custodians of the artform. Called the phad (literally meaning screen), a fifteen foot long hand-painted fabric scroll is at the heart of this tradition.

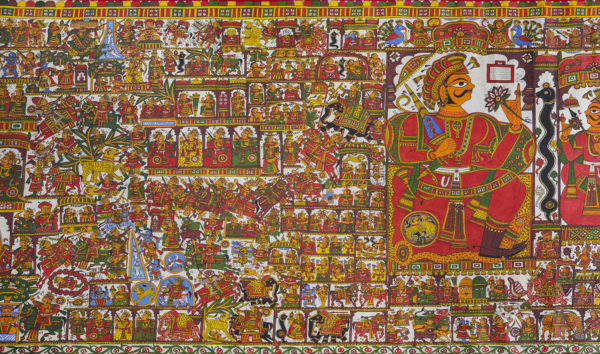

Pabuji ki Phad (detail), 20th century Unknown Maker(s) Natural pigments on cotton fabric

Worshipped as a demi-god who protects cattle, Pabuji is one of the most venerated figures in the Rebari community of Rajasthan. Tales about his life are painted on the phad (horizontal scrolls) by the chitrakar and handed over to the deity’s head-priest called the bhopa. The phad is more than just a storytelling device. For a community always on the move, it is venerated as a portable shrine and the performance of the phad is viewed more as a ritual than entertainment.

The bhopa is also the storyteller-performer. As the sun sets in the desert, the phad is unrolled and songs of Pabuji’s brave exploits and unimaginable miracles are sung. A small lamp is lit by the bhopi (the bhopa’s wife) and moved around to illuminate sections on the phad that the bhopa is singing about. Owing to the size of the phad and the length of the story itself, sometimes a single performance may stretch till daybreak (with ‘tobacco’ intervals for the audience, much like popcorn breaks during a movie!). Often a performance is divided into sections, and sessions can be hosted through continuous nights if the audience is enthused enough.

One village, many stories

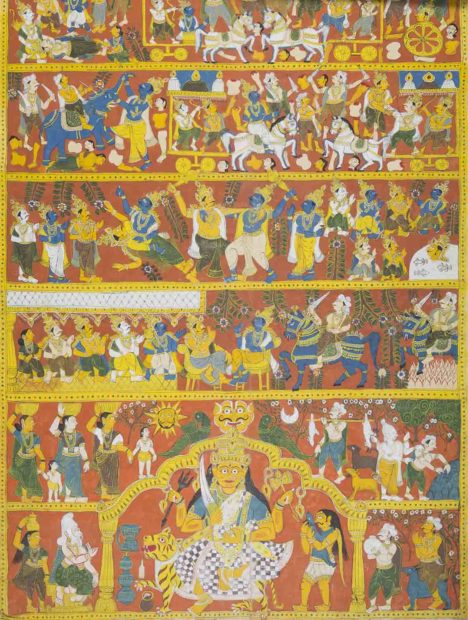

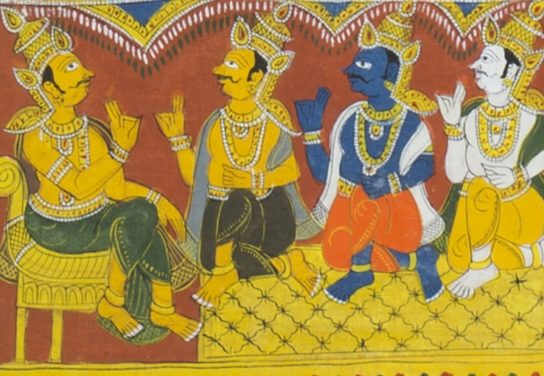

Another tradition of story-scrolls can be found in the village of Cheriyal in Telangana. The painters of the cheriyal scroll were originally map-makers for royalty who moved to painting, their surname ‘Nakash’ (from ‘Naksha’ that literally means maps), still carrying a remnant of that history. Working in collaboration with the storyteller, they paint scenes from myths and epics, as well as from local folklore and legends and pass them on to be used in a performance. The paintings in these scrolls are characterized by densely packed figures depicting multiple episodes and the predominant use of red, gold and blue.

Cheriyal Scroll, 20th century, Unknown Maker(s), Natural pigments on paper

Each community in Cheriyal has their own brand of storytellers and archive of legends and stories that are painted on specific scrolls. In addition to the scrolls, the cheriyal artists also create masks and wooden puppets of the characters which are then used by the storyteller in his theatrical performance of the story involving music and dance.

Cheriyal Scroll (detail), 20th century Unknown Maker(s) Natural pigments on paper

Even though these painting traditions don’t enjoy the same level of popularity today, with many struggling to stay relevant, our enjoyment of stories remains unchanged. The way we tell stories may have taken a variety of new forms, but at its core, it is still this simple act of coming together, sharing and imagining. In front of a desert sunset or a suburban screen, our hearts are still warmed by a great story which holds the ability to motivate, move, challenge and call us to action.

Our stories are our voices, they are tales of our collective histories, shared values, struggles and triumphs. We carry them with us and pass them on to future generations. Like Pabuji of the desert, perhaps our stories are what make us live forever.

Korom Binti Pata(detail), 20th century, Unknown Maker(s), Natural pigments on paper