Essays

The liminal between hi & bye

Vinay Kumar

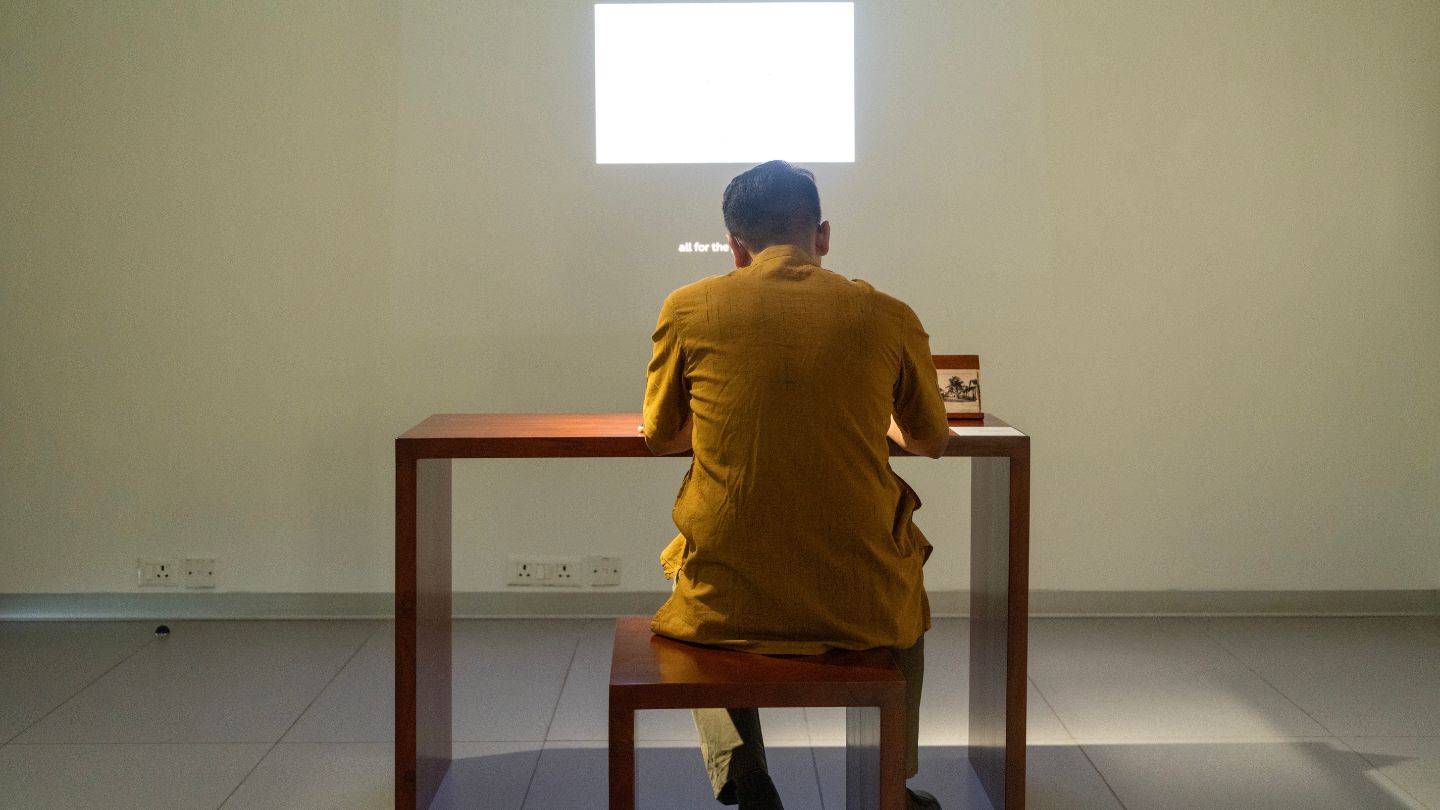

The table at the end of the room was lit by a warm overhead lamp, on it was an open box full of reprints of picture postcards from early twentieth-century India. Postcards were projected on the wall facing the table with voiceovers reading the content. The exhibit at the Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), Bengaluru in the Infosys Foundation Gallery titled- Hello & Goodbye: Postcards from the Early 20th Century, is a speedy glance into the lives of people living in or visiting early twentieth century India. On one side of the postcards are worded stories and on the other, pictures of India worth a thousand words.

The exhibit hosts 100-150 postcards from a larger collection of 1300 picture postcards. The displayed postcards are only a brief glimpse into the collection, presenting India and Indian culture for the Western gaze. The exhibit focuses on this visual culture and practice in India. It underlines the photographic choice and the postcards’ effort to project and promote India. A story of India. A beautiful and exotic India. And an India that needed the British invasion? The exhibit offers an opportunity to read a story of colonial India. Post-colonial theory and research come to life in this exhibit.

Pictures from the colony

“Colonialism can be defined as the conquest and control of other people’s land and goods” (Loomba 8).

The British had access to the resources of India and the first shot at archiving a plethora of undocumented history and culture. The formidable colonial archives, company paintings and documentation preserved in the British Library are a testament to their archival instincts. Print and photographic material from these efforts have regularly entered popular culture since the twentieth century. The choice of pictures in these cards tells of both what the British saw in India and the vision of India they wanted to project to the world.

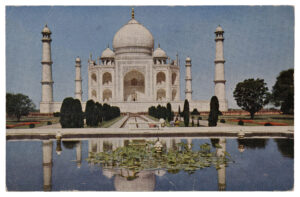

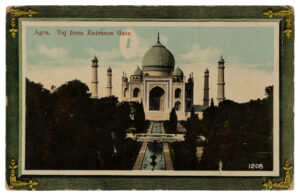

Images of the Taj Mahal, palaces and architectural features were sometimes incorrectly cited but mass-produced and largely circulated. There were cards with photos of deities most often labelled Hindoo, religious looking ceremonies, men and women engaged in various laborious activities like pottery, toddy tapping and other ‘daily life’ activities; there were also photos of snake catchers, Raja Ravi Varma painting reprints, Christian missionary photographs of children, studio photographs of Parsi women, musicians, and dancers. The famous photograph ‘A Nautch Girl’ from before the 1900s is found behind a postcard. It is possible to see what might have been acceptable and understandable from India to the world and what is shocking.

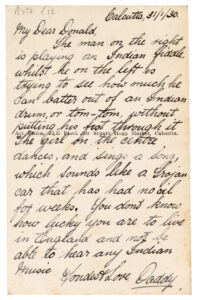

The prints offer an opportunity to expand our understanding of the colonial period. While extensive postcolonial scholarship offers insights and means to understand the structural nature and power relationships, the personal but public narratives of the individuals on these cards show us the nuances in their lives. Some postcards are conversations between women collecting architectural photo postcards, another between a young French woman and her aunt exchanging life updates including details about her new life and mother-in-law. There is also a brief card from a young child to their father.

The pictures themselves offer a couple of different and interesting observations. The obsession with the Taj Mahal is evident; the larger collection had nearly 100-150 picture cards with the Taj Mahal on them. The image of India during the early twentieth century was that of an ‘exotic’ other with majestic landscapes, fantastic beasts and unbelievable sights. The choice of temples, pagan deities, ritual ceremonies, communal activities, markets, people engaged in unusual activities and bare-chested priests are images of the exotic that also help underline the ‘social backwardness’ to justify the colonial imposition of their morality, equality and not necessarily justice.

Signed picture postcards from famous landmarks, monuments and architectural structures are today’s equivalent of a selfie with a monument or structure on people’s social media. Picture postcards were souvenirs and an opportunity to brag about travels in the early twentieth century.

Private or Public

Postcards lie in the precarious and liminal place between the public and private. They are never meant for private and sensitive information but a conversation between familiars, and reading such an exchange at the least is an intrusion. The morality of this intrusion is debatable but it is undeniable that the archive offers interesting glimpses from an ethnographic point of view. Some of the postcards hold brief and racist remarks on the monuments or the visitor’s experience while visiting. It provides a glimpse of an attitude that is historically recorded.

This and my conversation with the curator only confirm the exhibit’s attempt to curate an honest experience of navigating the large volume of postcards. The material has not been tailored or cured for an aesthetic or to recreate colonial nostalgia. It instead helps the audience immerse in their love for postcards. The tactile experience helps engage with the narratives and the exhibit ends up holding up a mirror to show us an India that only the world outside is familiar with.

The many postcards and words that have survived the last century while waiting to be read will leave you to wonder about the past, India’s history in print, and the liminal space between the hi and goodbye of a postcard. I walked out of the Infosys Foundation Gallery where the postcards are shimmering under warm and yellow hues that may have stuck to my skin like the embellished glitter postcards in the collection.

References:

Loomba, A. (2015). Colonialism/Postcolonialism (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315751245