Essays

Art as Witness: 75 Years of Partition

Krittika Kumari

Exploring the artistic landscapes of post-Partition India and Pakistan in collaboration with the ZVM Rangoonwala Foundation, featuring works from the VM Art Gallery Permanent Collection and MAP.

A landmark event that shook the subcontinent, the Partition and its memories linger through myriad stories: accounts of loss, separation of families, friends, and neighbours; and a breakdown of camaraderie between the citizens, Hindu and Muslim. The resettling of geographies and its aftermath continue to seep into public consciousness. Within this charged space, what role does art play? How does art bear witness?

In both India and Pakistan, artists have looked towards the Partition for inspiration, interpreting and expressing its effect on them in different ways. Seventy-five years later, while we continue to experience the after-effects of the Partition, art allows us to find a connection with our neighbours through works of several modern and contemporary artists on both sides. Art created in response to the Partition can function as a living archive, allowing audiences to reflect and identify with their histories.

As second-generation witnesses to what became known as the Long Partition, innumerable questions arise. Who was documenting the Partition? How were artists (writers, photographers or painters) responding to it in real time? What do the works convey about that particular period? Are they individual responses or representation of a collective memory, or both? In collaboration with the ZVM Rangoonwala Foundation, this essay looks at works from the VM Art Gallery Permanent Collection and the MAP collection, exploring how artists have responded to and experienced the Partition. Centering the notion of the witness, the essay moves from first-hand perspectives to that of an observer, exploring depictions of trauma, questions of identity and displacement, political dissent and alternative approaches to expressing the Partition’s aftermath.

The Trauma of Partition

There were several artists who experienced the Partition first-hand. Drawing from refrains of violence and trauma, artists on both sides of the border have referenced the Partition in their work. From 1946 onwards, the undivided nation became riddled with unimaginable violence, based primarily on religious and communal lines.

The angst of this shared history is visible in the works of artists through subject matter or an evocation of underlying emotions via style and technique.

Drummer, Tyeb Mehta, 1988, Oil on canvas, H. 115 x W. 90 cm, MAC.00459, Collection: Museum of Art & Photography (MAP)

For Indian modernist Tyeb Mehta, his violent and melancholic memories of the Partition, particularly of a man being killed before his eyes, occupy a prominent place in his imagery. Fractured figures, distorted lines, vibrant colours, and the use of the diagonal in his works are all representative of human suffering. Fragmentation and the diagonal line were, in particular, metaphorical of the Partition for him: they represent the violent division of the land as well as a contemplative bifurcation between the individual and the collective, the secular and the religious.

The drummer, who would partake in festivals and joyous celebrations, is instead depicted as a harbinger of doom in Mehta’s work, featuring a bisected body and an expression of anguish. He beats on his drum in a frenzied state, perhaps signifying the metaphorical abyss that society was hurtling to at the time.

The flat colour planes bring the macabre figure into focus, urging viewers to contemplate the trauma and suffering inseparable from the memories of the Partition and its aftermath.

Untitled (Mosque), Francis Newton Souza, 1975, Oil on canvas, H. 42.9 x W. 58.1 cm, ©VM Art Gallery Permanent Collection

Do Souza’s distorted figures reflect the turmoil of the Partition? While Souza’s personal life contributed to his rage and dissatisfaction, the Partition and its after effects likely impacted him, given that he was living in Mumbai as a young artist when it began. This painting from 1975 by the artist depicts a mosque which he often passed during his train journeys between Karachi and Lahore post-Partition. A red building, presumably in the style of Mughal architecture as suggested by the bulbous dome and minarets, stands amidst lush, unkempt foliage.

During the 1970s, when this work was created, Souza visited Karachi upon an invitation from the prominent art collector and artist, Wahab Jaffer. During his stay in Karachi, Jaffer introduced Souza to practising artists in Pakistan, such as Bashir Mirza. Following the initial visit, Souza began visiting Karachi more frequently and exhibiting his work at the Indus Gallery, (the first gallery of its kind) founded by Ali Imam in the 1980s. As a result, Souza developed friendships and connections with artists across the border over time.2 These connections are significant as they showcase the dialogue between South Asian modernists, and how they artistically influenced and paved the way for one another.

The Liminal Space: Displacement and Identity

The socio-religious dislocations engendered by the Partition created fractured identities. Sadaat Hasan Manto reflects on the absurdity of this enforced migration in his short story, Toba Tek Singh:

“Two or three years after Partition, the governments of Pakistan and India decided to exchange their lunatics in the same way that they had exchanged civilian prisoners. In other words, the Muslim lunatics in Indian madhouses would be sent over to Pakistan, while Hindu and Sikh lunatics in Pakistani madhouses would be handed over to India.” 3

At the end of the story, the protagonist lies between two borders. Anwar Jalal Shemza and Zarina Hashmi both experienced this sentiment. While both artists lived in Pakistan post-Partition, they immigrated to different cities in Europe during the course of their lives and both captured the feeling of ‘wanting to be home.’

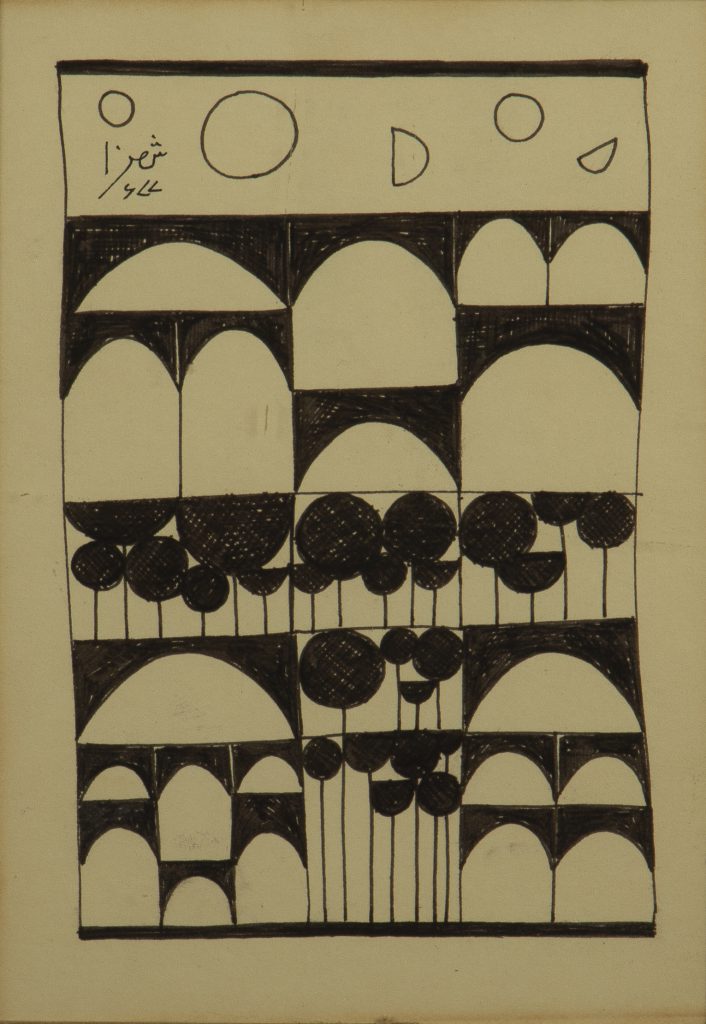

Architectural Drawings, Anwar Jalal Shemza, 1977, Pen and ink on paper, H. 17. 8 x W. 12.7 cm, ©VM Art Gallery Permanent Collection

Anwar Jalal Shemza’s art practice is built upon his diasporic identity, having lived in Pakistan and later in the United Kingdom. Born to Kashmiri and Punjabi parents in Shimla (part of modern-day India), Shemza moved to Lahore in 1944 to study traditional miniature painting and learn about Islamic art at the Mayo School of Arts. His family settled in Pakistan post the Partition between 1947 and 1950. Within a decade of the Partition, Shemza moved again, this time to study at the Slade School of Fine Arts in London. While in London, he went through a kind of existential crisis and destroyed all previous work to begin afresh; to find a voice that was perhaps more representative of his identity. This stylistic change led to the formation of his distinct visual language which combined Islamic and Western aesthetics. Although the artist attempted to move back to Pakistan four years later, he found it difficult to settle there. What he experienced was a misplaced sense of belonging which prompted the artist to move back to the UK within the year.

Shemza’s visual language is primarily composed of shapes, forms and colours, as seen in Architectural Drawings. He reduced the structure of buildings and his surrounding environment, whether an Islamic architecture building in Pakistan or the rural landscapes of Stratford, England, to simple shapes, blurring any form of identification or recognition of the land depicted. An ambiguity of belonging, related to his multiple shifts between India, Pakistan and England, is reflected in his drawings and paintings. Despite having lived in England for over two decades, Shemza expressed a desire to return “home” to the foothills of Kashmir in India in his old age, which remained unfulfilled as the artist passed away in 1985 in Stratford.4

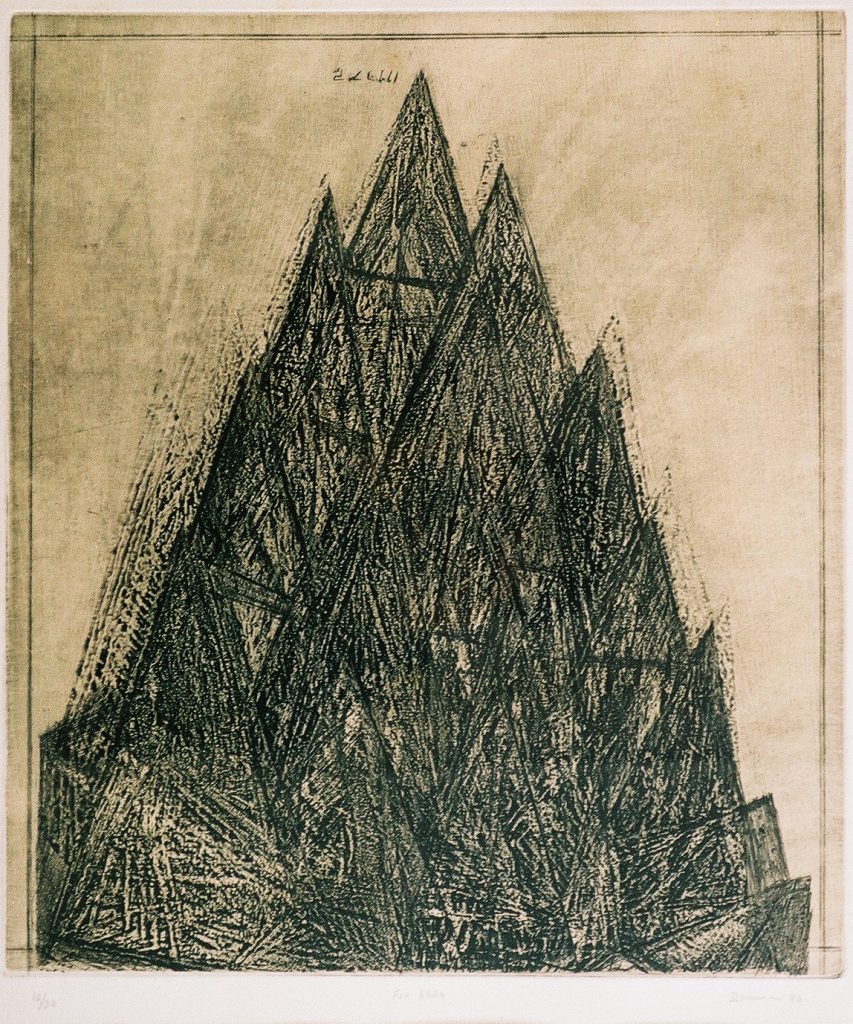

For Abba, Zarina Hashmi, 1986, Etching on Paper, H. 49.5 x W. 40.6 cm, ©VM Art Gallery Permanent Collection

Zarina Hashmi’s (referred to as Zarina, as preferred by the artist) vast body of work addressed themes of home, identity and belonging. As an itinerant artist, Zarina’s experiences were multifarious. An Indian-born Muslim, the Partition and its accompanying religious riots forced Zarina’s family to leave behind their ancestral home and relocate to Karachi to find safety. Although she returned to Aligarh for a short period to study, her marriage to a diplomat led to many relocations, from Bangkok to Paris and back to New Delhi. Following her husband’s death in 1977, Zarina settled in New York; however, she never stopped longing for her home and expressed this nostalgia, and a search for identity through her art.

The mountainous-looking forms in For Abba are perhaps a reference to her childhood home in Aligarh, which her family had to leave behind. The ominous black structure is rendered in urgent, jagged strokes.

A small inscription in her mother tongue, Urdu, reads the emotionally charged title of the work: For Abba, which translates as a dedication to her father. A sense of exile and a quest for roots linger in Zarina’s work. Her works bring forth memories of displacement and loss, and yet offer a space of solace for those whose lived experiences are similar to hers.

Political Leadership

Since 1947, India and Pakistan have experienced political upheaval and a general uncertainty in terms of leadership. India’s political journey as an independent country began with Jawaharlal Nehru who passed the baton to other powerful leaders, including Lal Bahadur Shastri and Indira Gandhi, who are among the most controversial and documented leaders of the post-Partition period. Pakistan too struggled with political stability, oscillating between autocracy and democracy, and between a government that was secular or Islamic. As a result, satire and civil commentary is a prevalent theme in both countries. Artists have been documenting leaders, events and changes since the 1950s, using it as a means to voice their opinions and sometimes, to voice the effects of these changing structures.

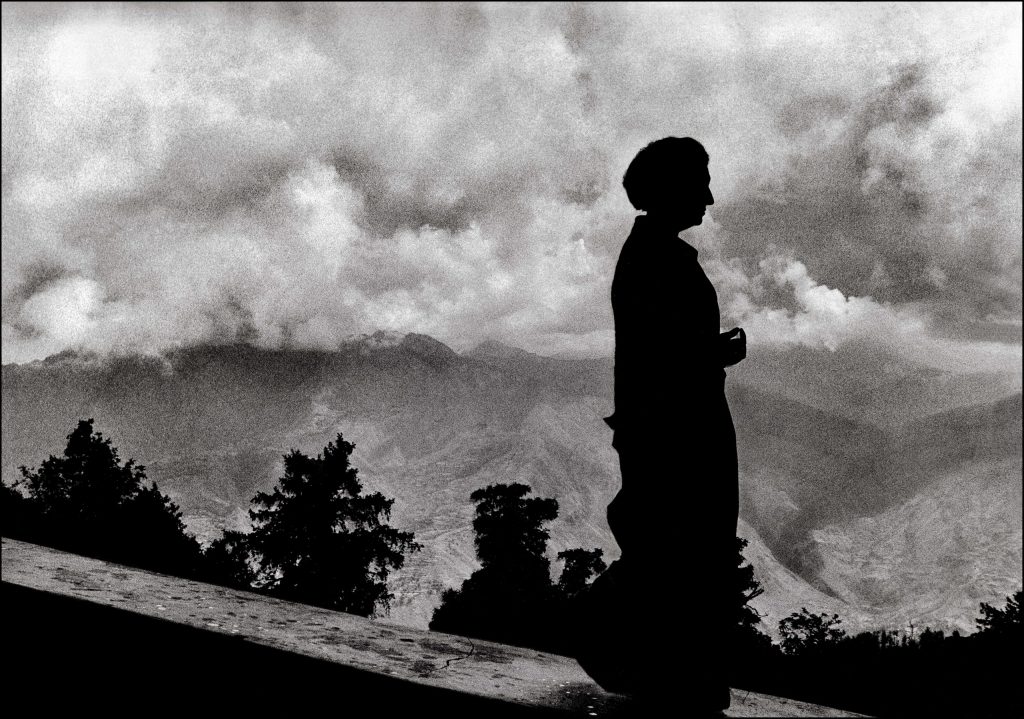

Indira Gandhi against Himalayas, Raghu Rai, 1972 (printed later), Archival pigment print, H. 60.7 x W. 79.4 cm, PHY.07074, Collection: Museum of Art & Photography (MAP)

As a leader, Indira Gandhi was a polarising figure. While some believe she was the strongest leader India has ever seen, others criticised her decision-making which deeply affected the country’s socio-political landscape. Gandhi instituted a state of Emergency in the country from 1975-77, a highly contested decision. Considered the darkest period in India’s history, the Emergency led to a suppression of political opposition, censorship and a suspension of constitutional rights.

Gandhi was later assassinated in 1984, in the aftermath of Operation Blue Star, where she ordered members of the Indian Army to storm the Golden Temple, resulting in the death of civilians. Her lasting political career has been documented by Magnum photographers, Raghu Rai and Marilyn Silverstone, whose images attempt to capture the women behind the political myth, to highlight her virtues and her flaws.

Born in 1942 in a village called Jhang, which is now part of Pakistan, Raghu Rai, experienced Partition as a young child. Through his photographs, he sought to express India’s changing social and political narrative in a post-Partition era. In this photograph, Rai captures Indira Gandhi in a moment of introspection, her silhouette against the hazy backdrop of the Himalayas covered with clouds, urging the viewer to focus on the figure; not her as a leader, but as a human being. Reflecting on his photographs of Gandhi, Rai wrote, “When I started doing this, I realised that if someone in the future didn’t know who she was, and what a strong personality she was, what a tough leader she proved to be, perhaps they would realise that by looking at these photographs. I began to ask myself, does this picture stand the test of time by itself, for itself? These pictures of her capture some of her essence.” 5

The Address, Bani Abidi, 2007, Diasec, c-print on paper, H. 70.1 x W. 106.6 cm, ©VM Art Gallery Permanent Collection

In 1948, a year into the foundation of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (also known as Quaid-E-Azam), the nation’s founder and chief leader, passed away. His enigmatic energy as a leader and his inclusive ideals are celebrated till today. Jinnah was important in setting up Parliament and laid the foundation for political and economic structures. However following his death in 1948, there were many questions left unanswered as to the distribution of political power. The political structures that Jinnah had formed centred around Parliament passing legislation and the Prime Minister governing the country.6

Post 1948, provincial leaders started to gain autonomy and retaining a centralised government with clear political structures became an uphill challenge for successive leaders.

Bani Abidi’s work from 2007 speaks of this political turmoil. Born in Karachi in 1971, Abidi completed her education at the National College of Arts in Lahore, Pakistan. Having experienced the after-effects of Partition, Abidi raises questions about leadership, states and power. In this work, she depicts a vacant seat against the backdrop of a painting that resembles the set used by leaders and presidents for televised speeches. The backdrop also includes a framed portrait of Jinnah. The artwork was displayed on several television sets and placed in public spaces across Lahore. What strikes in her image is the vacant seat, leaving the audience wondering whether an announcement will be made. In Abidi’s words, “The work hopes to raise questions about the relationship between civil society and the ever changing face of political power in Pakistan.” 7

A Space for Women

As the political landscape in both countries continues to change under various leaderships, often it is the position and role of the woman that is most affected by it. Even though women artists have been practising since pre-Partition, their names are often excluded in the study of the subcontinent’s history. In both countries, women artists had to carve a space for themselves in the art community, with many finding recognition in the middle of their careers. The works of women artists are thus charged with emotions related to horrors of the Partition, and the injustices faced by women in everyday life.

The Life and times of…, Salima Hashmi, 1983, Mixed Media on Paper, H. 48 x W. 45.4 cm, ©VM Art Gallery Permanent Collection

Born in 1941 in New Delhi, Salima Hashmi is the daughter of the famous poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz and has been an active artist since the 1960s. Her family migrated to Pakistan during the Partition during which she witnessed violence and carnage first hand. Born into a household that maintained strong social and political commitments, Hashmi always remained affected by the socio-political climate of her nation. The Life and times of… is part of a series of works completed in the 1980s against the backdrop of military dictator, General Zia Ul Haq’s regime in Pakistan.

Zia Ul Haq anointed himself as the President of the nation in 1978 and went on to establish sharia law, through which the governance of the state was expected to follow the Islamic doctrine. Under his dictatorship, the nation went through extreme hardships that was perhaps second to the Partition in Pakistan’s history. In speaking about her work, Hashmi states that “It was very much to do with the political context at the time {General Zia’s regime} but also dwelt on women’s covert histories which run parallel to the more public scenarios.” 8

In this work, Hashmi depicts a naked female figure, confined within the walls of her room, looking out at the carnage in the streets: a city ablaze with machine guns, fire and destruction. Yet, the focus of the work is the figure: stripped of all her clothes, and metaphorically her life. Windows in her work are often suggestive of hope and optimism; however here, they signify the windows of a prison, which is also a reference to her father and husband having been arrested for their political views.9 It is through her solitary female figure that Hashmi expresses her rebellion and protest against the oppression that women have faced. Hashmi remains a key figure when it comes to reflections and discussions on the Partition, its impact and the role of women artists in the wider artistic diaspora.

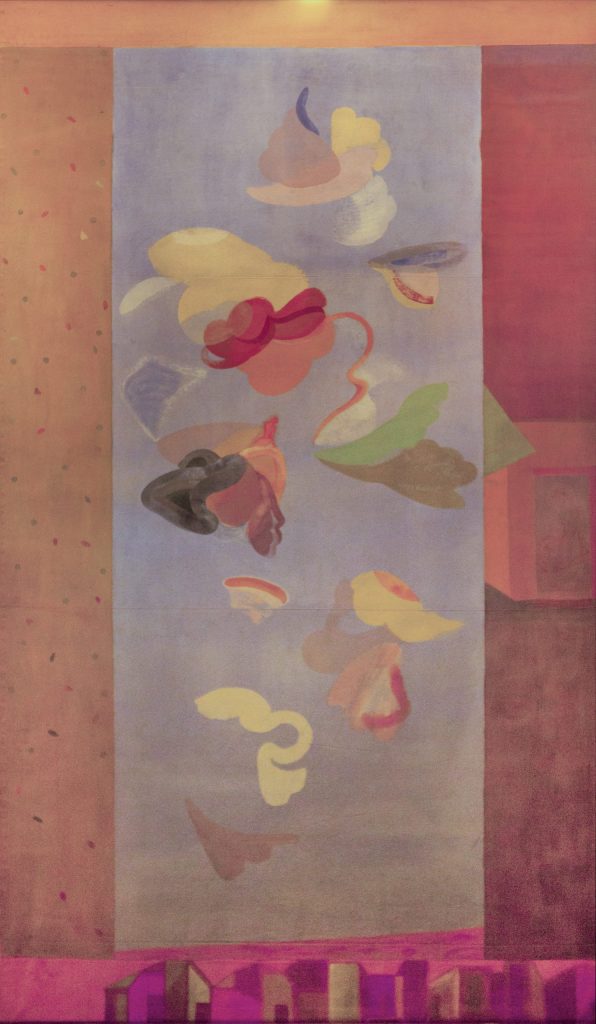

Meghadoot (Song Space series), Nilima Sheikh, 1995, Casein tempera on canvas, H. 287 x W. 158 cm, MAC.00684-2, Collection: Museum of Art & Photography (MAP)

Born in New Delhi in 1945, Nilima Sheikh grew up in a newly independent India post-Partition. Although she would have been too young to witness the Partition as it happened, Sheikh often references its impact on the country and its people in her artworks. In Baroda, she met her husband, the artist Gulammohammed Sheikh, and formed a network that comprised largely male artists. Observing the different experiences she had as a woman, as compared to her male contemporaries, Sheikh’s language automatically took on a “feminist” voice. Even today, Sheikh’s body of work focuses on violence, politics, poetry and most importantly, the feminine experience. Her visual vocabulary is distinct in depictions of beautiful landscapes that are evocative of loss, pain and struggle. Through several layers, her works build upon the Partition, narratives of Sindh (pre-Partition Punjab), the history of Kashmir and violence against women, especially young Indian brides.

This vertical scroll painting, part of Sheikh’s Song Space series from the 1990s, is lyrical and delicate in its translucent rendering, yet impactful in its metaphors. One side of the scroll is titled Meghdoot, referencing a poem by Sanskrit poet Kalidasa in which a man banished to a remote region asks a cloud to deliver a message to his wife.

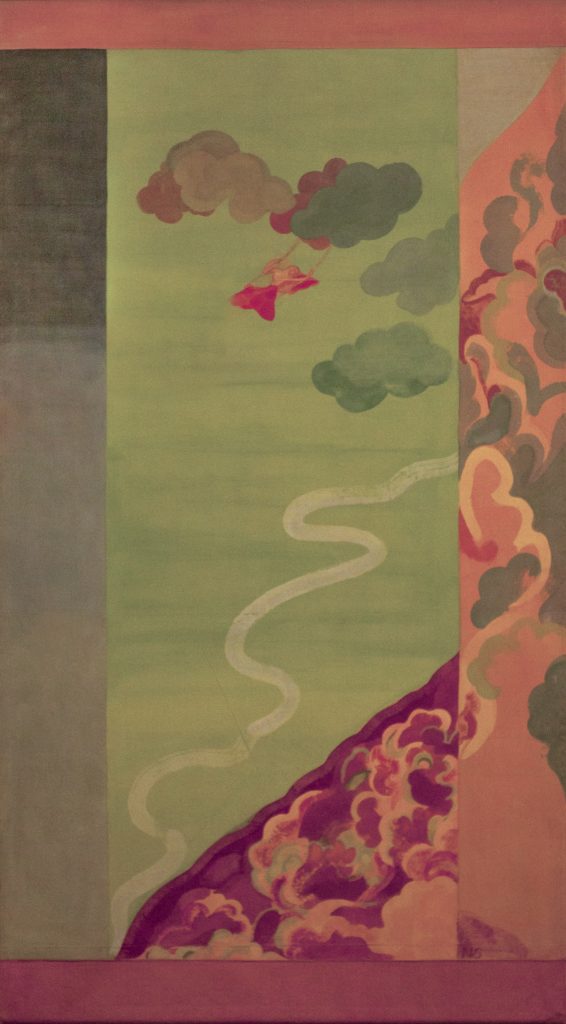

Sawan 2 (Song Space series), Nilima Sheikh, 1995, Casein tempera on canvas, H. 287 x W. 158 cm, MAC.00684-1, Collection: Museum of Art & Photography (MAP)

The other side of the scroll depicts a river running across a blood-hued landscape, through which Sheikh references the popular tragic romance stories of Sindh, such as Sohni Mahiwal and Heer Ranjha. In both stories, the woman is separated from her lover and forcefully married to someone else only to be killed later by their family members as punishment for defying them. The story and Sheikh’s work is a stark reminder of the plight of women in a patriarchal society. At the same time, Sheikh’s work is also a nod towards the many traditions and stories of Sindh that were forgotten because of the Partition. Like Meghadoot, Sheikh refers to this ‘desire’ to unite, with figures from Sohni Mahiwal and Heer Ranjha, and perhaps also to unite with her land pre-Partition. Sheikh also grew up watching operatic productions of these tragic love stories which were staged at a time when those residing in the north of India were experiencing the traumas of the Partition. The division of land and the tragedy it instigated were mirrored in these love stories that were marred by the separation of lovers.

Representation of the Everyday

Artists responded to the Partition in multiple ways. Some artists moved away from depicting the horrors of the Partition, to more serene subjects, such as portraiture and landscapes. This provided artists a unique way of protesting, fuelling feelings of nationhood or even establishing a continued sense of identity in the wake of the political and social strife that engulfed the subcontinent during and post-Partition in the 1940s.

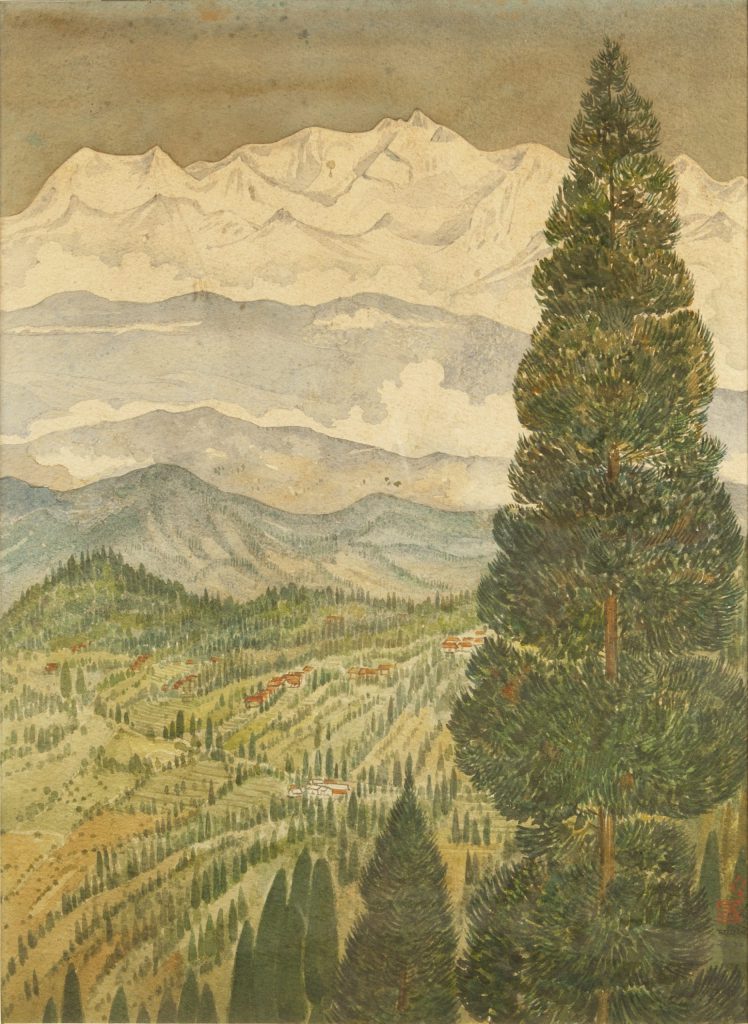

Landscape, Indra Dugar, 1950, Watercolour on paper, H. 49.5 cm, W. 36 cm, MAC.01204, Collection: Museum of Art & Photography (MAP)

Shukla Sawant writes, “Landscape representations came to stand in for the country as a whole, and attempts were made to arouse patriotism as part of a nation-building process.” 10

Indra Dugar’s work is from a time when a newly-independent India was finding its feet, while healing from the wounds that the Partition left behind. Idyllic landscapes that were untouched by the violence of the Partition, such as this image, acted as a reminder of the nation’s past and of peaceful times. The nostalgic representation perhaps offered a glimmer of hope and reassurance that reattaining the lost sense of unity and brotherhood was possible; that rebuilding India was not a distant dream. Millions in the country had suffered the same pain and melancholy, and images that stood as reminders of the past allowed people to reminisce their shared histories together.

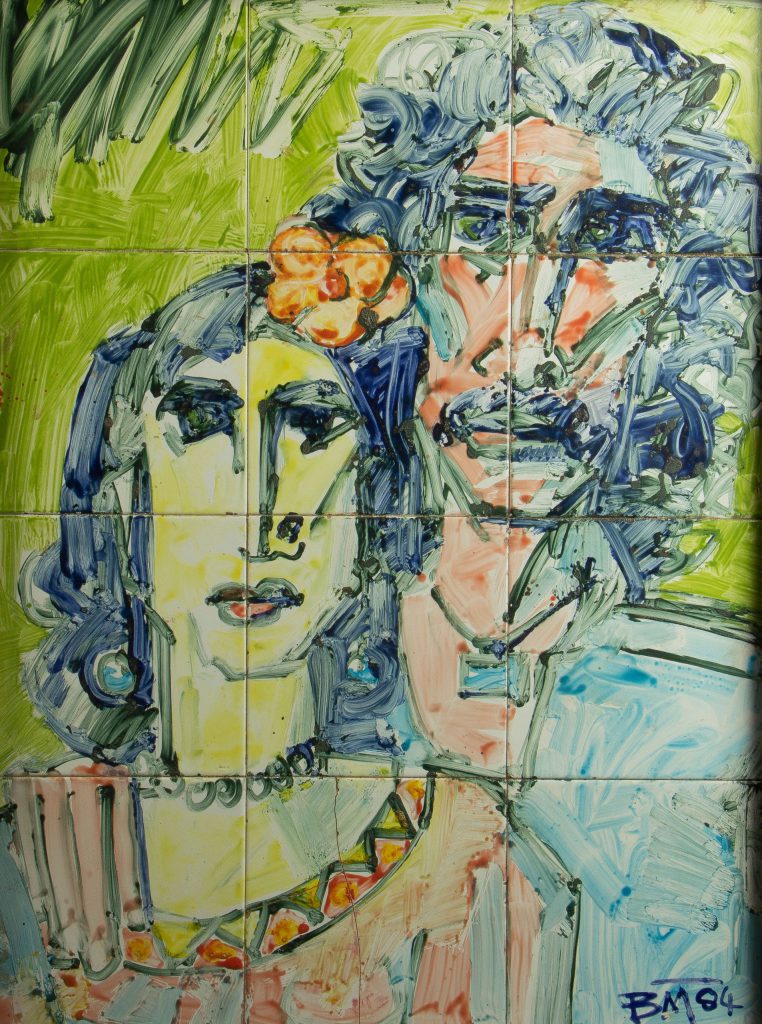

Bashir Mirza was born in Amritsar (part of modern-day India) in 1941, and later relocated to Pakistan with his family during the Partition. He studied at the National College of Arts (known as Mayo School of Arts pre-Partition) where he and his fellow students were encouraged to look towards Islamic traditional art heritage as well as their immediate environment for inspiration. Although trained in graphic design, Mirza’s body of work often referenced the socio-political climate of the country and its effect on the citizens, which included works on wars, dictatorship of the Zia-Ul-Haq period in the country and more.

Untitled, Bashir Mirza, 1984, Glaze on ceramic tile, H. 81 x W. 59.4 cm, ©VM Art Gallery Permanent Collection

As a child, Mirza witnessed his family suffer through poverty and migration that came with the Partition, all of which left an indelible mark on his work. In his People of Pakistan series, he chose to create a newfound identity and sense of kinship through moving portraits of common people.

This portrait, depicting a male and female figure, was meant to document the typical characteristics of men and women in Pakistan, particularly those from the north of the nation. For example, as portrayed in the painting, men have curly hair and wear a necklace around their neck which has a prayer inscribed on it; while, a nose ring and necklace, paired with a salwar-kameez, is common for women. The series, thus, acted as an establishment of the identity of Pakistan and represented the various communities in Pakistan at the time.

The artists and themes highlighted here are just a fraction of the lasting impact the Partition has had on art and literature. The Partition’s cultural, political, economic, and psychological influence on South Asia still continues to affect communities in the diaspora. Contemporary art across borders remains a witness and also a facilitator of conversations and connections between the two nations. For instance, The Pind Collective, a collaborative, virtual initiative from 2016, brought together artists from both countries to exhibit works that evoke a sense of ‘home’ on one common platform, and in the process establish meaningful relationships with one another, founded on shared histories and experiences.

Memories of the Partition remain embedded in collective consciousness on either side of the border. While time may not heal wounds, can art help re-establish our association with each other?

About VM Art Gallery

VM Art Gallery endeavours to create a space where experiences with art can spark important and much needed dialogue, create room for learning, and make a positive social impact while sustaining a climate of curiosity and interest in the unfamiliar. It is our belief that the arts can contribute immensely to social welfare through a positive and reinforcing impact.

VM Art Gallery was founded within the Rangoonwala Community Center as part of the Rangoonwala Trust in 1987 to promote art education, fine arts and to provide a much needed outlet for artists, old and young, to display their works befittingly. Under the capable leadership of Riffat Alvi the gallery became a pioneering force in the Pakistani Art scene.

The VM Art Gallery is also one of the only institutions in the city with a rich and growing collection of works by Old Masters and Modernists from Pakistan, currently in the process of being digitized. This archive serves as a site for research and study into Pakistani Art History as well as curatorial investigation for exhibitions.

About ZVM Rangoonwala

Founded in 1976, the ZVM Rangoonwala Foundation is a registered charity in the UK. It was set up by the Rangoonwala Foundation to donate to registered charities inside and around England, Scotland and Wales. ZVM Rangoonwala Foundation’s objective is to provide financial support for exclusively charitable purposes – education, health, livelihood, art and with a strong focus on disability.

Krittika Kumari is the Digital Editor at the Museum of Art & Photography, Bengaluru. A graduate of the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, her research interest lies in the Mughal miniature painting tradition, as well as Indian Modern Art.

References

1. Nishad Avari, “Francis Newton Souza — The ‘enfant terrible’ of Modern Indian Art,” Christie’s, March 1, 2022, https://www.christies.com/features/Francis-Newton-Souza-collecting-guide-10035-1.aspx.

2.“Francis Newton Souza,” Clifton Art Gallery, accessed August 12, 2022, https://cliftonartgallery.com/artist/francis-newton-souza/.

3. Saadat Hasan Manto, “Toba Tek Singh,” Words Without Borders, July 8, 2022, https://wordswithoutborders.org/read/article/2003-09/toba-tek-singh/.

4.“Biography: Anwar Jalal Shemza (1928-1985),” Anwar Shemza, accessed July 29, 2022, https://www.anwarshemza.com/biography.html.

5. Ellie Howard, “Indira Gandhi: The Centenary of India’s First Female Prime Minister,” Magnum Photos, November 2017, https://www.magnumphotos.com/newsroom/politics/indira-gandhi-centenary-india-first-female-prime-minister/.

6.“Birth of the New State.” Britannica, accessed August 12, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/place/Pakistan/Birth-of-the-new-state.

7. Bani Abidi ,“The Address, 2007,” Bani Abidi, accessed August 11, 2022, https://www.baniabidi.com/#/the-address-2007.

8. Salima Hashmi, Email to Kamila Rangoonwala, 6 August 2022.

9. Shoaib Ahmed, “From art to activism, the versatile Salima Hashmi has done it all,” Dawn, May 9, 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1622828; “Oral History with Salima Hashmi,” The 1947 Partition Archive, Stanford Libraries, January 18, 2016, video/text, https://exhibits.stanford.edu/1947-partition/catalog/ng115km5404.

10. Shukla Sawant, “In a New Country,” The Indian Quarterly, accessed August 2, 2022, https://indianquarterly.com/?p=2637.