Blogs

Why I Love Art: The Past is a Home

Mayookh Barua

Revisiting the meaning of “home” through the looking glass of Zarina Hashmi’s lines.

There is a frantic nature to newness. It looks less like blooming flowers but a gash on the body. There is no knowing why the orifice came about. Whether it is to open a receptacle to new orientations or a way to let blood out. But all we can hope is that we survive it.

New Delhi had slit opened that knowing in me. I realised it was unlike my home. A house is nothing more than a bunch of sticks tied together and made to stand upright. It is nothing more than a shade from the sun, a shield from the wind. The warmth when there is thunder. The height when there is a flood. But the home is where spirits live, music bleats, aromas of pulao sticks to the walls and water tastes sweet.

My home cradled in the Brahmaputra floated in scents of plumerias and night queens. I have voyaged out of it rather than escaped into the colonial contours of the capital city to find a life for my gay self. Amidst busy streets and brutal concrete buildings, I hoped to find refuge for my queer self. I presumed that in the city people are distracted so I could grow in the shadows of the street lights. But here I was hopping around hearts and houses, trying to find the comfort of my home since everything was too bright. Until I came across an artwork at a party at Khosla’s new art deco house in Nizamuddin. There at the center of the living room housed an extensive collection of abstract paintings, and amidst it a work that arrested me.

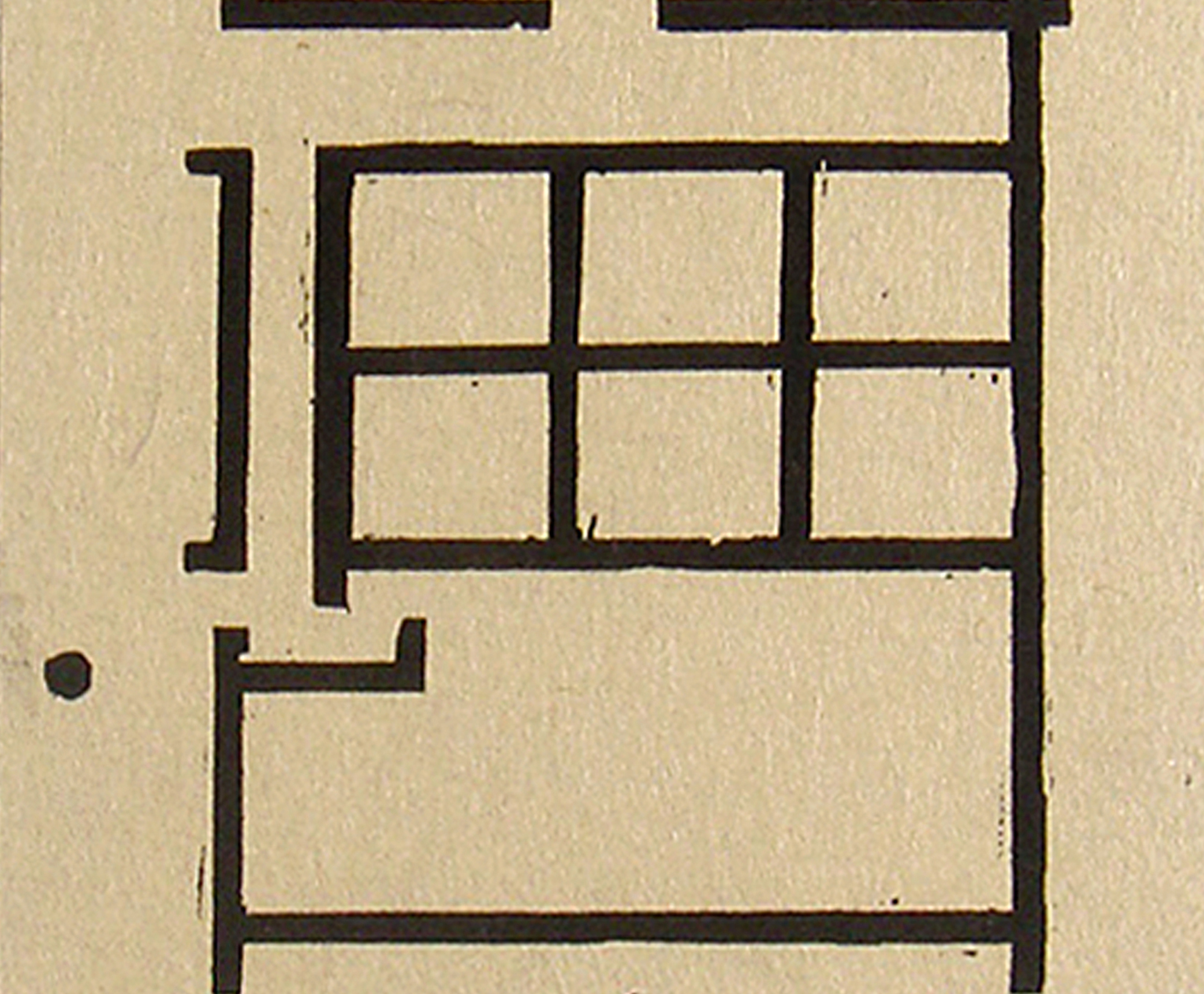

Home (Home is a foreign place) by Zarina Hashmi, 1999, Woodcut with urdu text printed in black on handmade indian paper mounted on somerset, 8 x 6 inches, Image courtesy: Gallery Espace

“Beautiful isn’t she? What do you think it is?” the host asked me. And before I could reply, he whispered “It’s by Zarina Hashmi. I believe it’s called Home is a Foreign Place.”

“Some kind of an outline,” I told him quizzically. I looked at the coffee-stained paper. The lines were soft, leading me to believe they were drawn using kohl. A house that looked not more impressive than something drawn by a kindergartener was framed in one. In another an arrangement of squares and rectangles with breaks on their perimeters.

“It is! It is the layout of the houses she moved between. You see she moved a lot. And every time she moved she could not take much but only the outline of the house she lived in.”

It charmed me – the thought of making an outline every time one left a place called home. Zarina Hashmi lived many lives in many cities. In each city, she found and left some part of her own.

He continued, “it’s never the house but the memory of the house. Never what the actual house looks like, but how she imagined it looked like.”

When we come to a new place we look for the reminisces of the home we have left behind because it provides us rest, reprieve, and reconciliation. But how do we find these things in the remembrance of a place which never stood for the same in the first place? I left home because in its confines my meetha-ness, as they say, had no room or doors, just closets. But I also remember home as integral to me, like skin and hair that I cannot and would not change. Through the looking glass of Hashmi’s lines, I recognised that we all need homes to go back to. When we don’t have one, we make them from the confines of our memory. Home looks like a memory of the past, one that we carry along.

Mayookh Barua is a North Carolina-based writer from India who identifies as a proud queer man. His areas of focus mainly lie in and around art, queerness, cinema, and the politics of a family within the Indian . He has previously published at Crooked Fagazine, Mezosfera Magazine, and District-Berlin.