Blogs

Why I Love Art: Arrested Audience

Saranya Subramanian

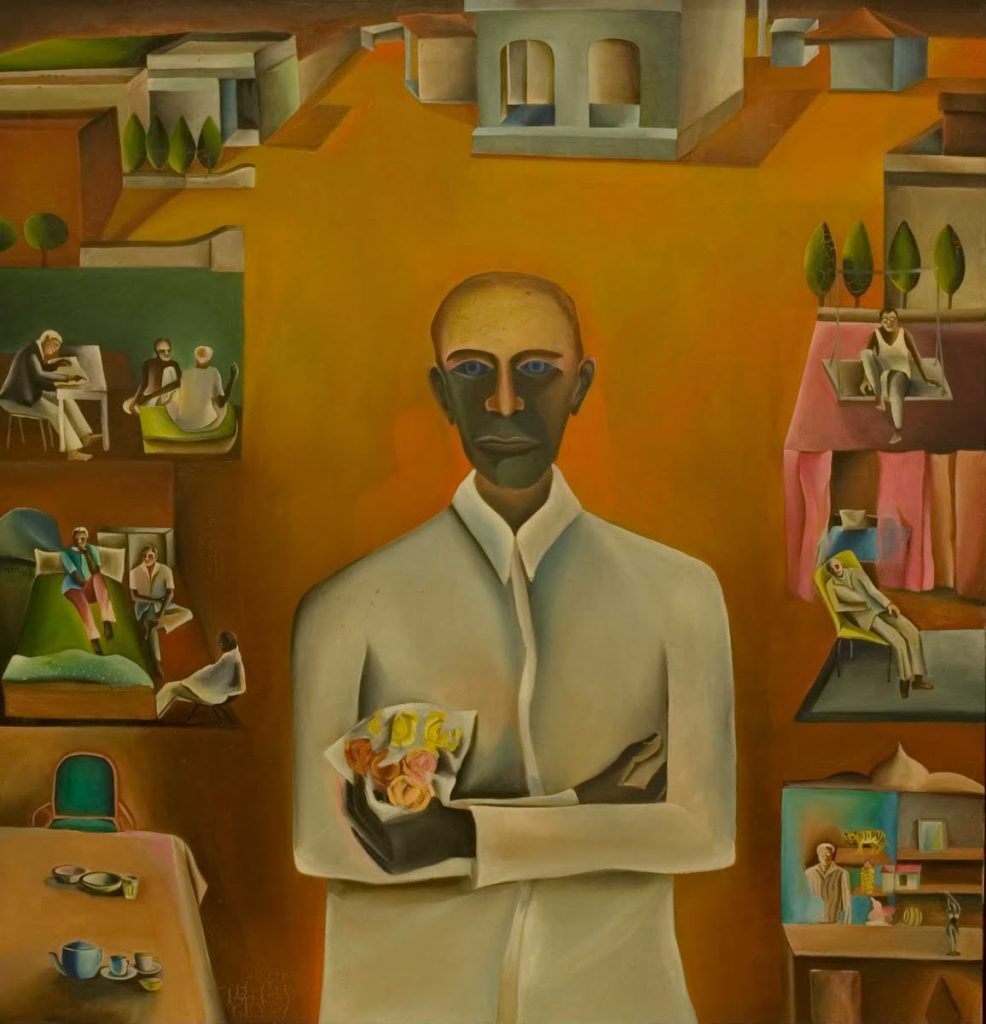

Why I can’t stop staring at Bhupen Khakhar’s ‘Man with Plastic Flowers.’

I will start with an honest declaration: I don’t know anything about art. I access the world through words. And while I have read about Bhupen Khakhar’s painting style, his use of flamboyant colours, graceless figures, his blending of Indian folk and pop art, nothing accurately describes what I feel––at a visceral level––when I look at Man with Plastic Flowers. I have read numerous pieces on this masterpiece, and while they tell me about its artistic details and socio-political urgency, those don’t really matter to me. The cultural relevance and subversive nature of Khakhar’s art are important, but aren’t the primary reasons why I keep going back to this painting, why I cannot stop staring at it. The primary reason is quite simple: because the Man is staring at me in the first place. I am, quite literally, arrested.

The word “arrest” comes from the Latin ad (at/to), and restare (remain/stop), which then became arester in Old French. To arrest is to halt, stop, freeze; to be arrested is to be halted, stopped, frozen. The English word today weighs heavily under political connotations; to be “arrested” is associated with the police, the law, the all-knowing, all-watching state. This idea of surveillance is also present in art. I, the audience, am watching a painting, but in some rare cases, the painting is watching me back. It’s a deeply tender moment: both seeing and being seen: acknowledging the other’s existence. I suppose this is how I feel when I see the Man holding a bouquet of plastic flowers. I see his routine play around him like clockwork, the various banalities that keep him in motion (and therefore alive), and I see him. What’s more – he sees me. When we see each other, we are strikingly similar. The only difference? He is holding onto something, while I have come empty handed. Plastic flowers are artificial, but long lasting, possibly speaking to the human desire to cling onto all that’s fake, illusory, maya. But maybe that’s just one way to look at it. Maybe he’s just holding a bouquet of plastic flowers. Maybe the painting is meant to be vibrant and puzzling, but above all else, emotionally experienced.

Man with Plastic Flowers by Bhupen Khakhar, c. 1975-76, Oil on canvas, Image credit: National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi

Not knowing anything about art, I discovered Man with Plastic Flowers when I was scrolling through social media a few years ago, and came to a screeching halt. So piercing were the Man’s blue eyes that they held my attention, convincing me to do the impossible: stop scrolling. At first, I was struck by the absolute assertion of the portrait. Khakhar’s paintings are always assertive: they are framed pictures of people who are here; in the present, in pain or bursting with joy, but they are here, living.

In 2016, art critic Laura Cumming reviewed Khakhar’s paintings: “He has no fluency or touch with the brush; he moves the paint around with laborious difficulty. Every canvas appears to be an almighty struggle, to the extent that the struggle threatens to mystify the subject.” Here was a critique of a painter I grew to love, telling me that his art lacks technical skill. I thoroughly disagreed with Cumming’s review but had no artistic knowledge with which to combat it. I could only speak for Bhupen Khakhar’s art personally, and that’s what made it so magical to me. I didn’t need to study his brushstrokes or read a history of primary colours to access this painting. I didn’t even need to look at it – I was first looked at by it, by the Man who looked straight at me, thus initiating a conversation. There is something intuitively moving about being seen. Even today, when I look at Man with Plastic Flowers, I am stopped, I am seen, and I am comforted through that recognition. I am arrested. And it is the most freeing thing I feel.

Saranya Subramanian is a Bombay-based writer currently pursuing an MFA at the University of San Francisco.