Blogs

What the Past Holds: Considering Postcards

Nihira Ram

Postcards. They’re stocked up in hundreds outside bookstores or souvenir shops. They also dot the walls of Bangalore’s Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) as part of its latest exhibition, Hello and Goodbye: Postcards from the Early 20th Century.

Postcards dot my bedroom walls. Especially those which have warm wishes scribbled at the back from friends now living far away. One devotes space for a poem by Emily Dickinson, another notes the importance of friendship. All of them whisper “I saw this and thought of you”. It was this thought that brought me to the exhibition. I wanted to understand how people thought of each other in the past. What did they share with each other at a time when long-distance communication wasn’t easily available? What can we learn about them, and in a way about colonial India, through this exhibition?

Today, postcard numbers have reduced but they still figure into the odd traveller’s memorabilia or as intimate gifts, like the ones hung up in my room. Light to touch, personal, yet signifying something bigger than the person having, sending or receiving them. You can see the appeal. A photo of the Taj Mahal with your writing on it- though no replacement for the real monument can function as a personalised inscription on the real thing. Hello, here are my words on the ‘symbol of love’. Goodbye, yours.

The postcard was an invention of the 1800s. A perfect mix of photo and text. Global production and circulation skyrocketed. Just like cotton. And just like cotton, postcards displayed in the exhibition reveal a much deeper history about colonial India, and the world. It probably isn’t an accident that postcards saw a boom after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 which led to a rise in international travel not just for trade or Empire but also for private recreation. Postcards are a valuable archive of visual information. They are also insightful archives of what people in that time thought counted as information.

Taj Mahal indeed does appear on numerous postcards from the early 20th century. What makes it so photogenic? Why is its visual architecture such an endearing global image even today? Is it because white marble is simply beautiful? Or because it was one of the most ambitious, international projects undertaken by a Mughal court connecting not just people and places within what is today India but also Sri Lanka, Tibet, Afghanistan, Balochistan, Uzbekistan, China, Persia, and the Arabian Peninsula? Or is there something more? Despite photography in India dating to at least 1840, there are surprisingly no photographs of the historical site until Dr. John Murray, a Scottish doctor and photographer in the employ of the East India Company’s Army-attached Medical Service took the first in 1858. What lagged this interest? It’s possible Dr. Murray, coincidentally stationed in Agra near the Taj Mahal, only took the photo because he was (formally or informally) commissioned to do so by the man who took control of restoring the mausoleum which was at the time in a dilapidated condition: British viceroy George Curzon. However, Curzon did more than restore. He transformed the complex charbagh (quadrilateral) gardens imported in style from Persia to lawns suiting more European sensibilities. Makes me wonder, why it was only after this aesthetic change, along with major repairs, that allowed the Taj Mahal to become ‘capturable’ for Europeans. Perhaps, Curzon thought any incoming visitors from Europe would be more at ease with the tomb if they first walked through familiar grass.

All this information is potentially lost on the largely foreign clientele who did indeed visit Agra and purchased a Taj Mahal postcard. The fact that they are seeing what is effectively an amalgamation of Mughal imperial endeavours and British colonial decisions. The fact that what they identify as uniquely ‘Indian’, is in fact a product of global trade that does not centre Europe. Yet, these postcards also provide information of their own. We can infer that the image of the Taj had become so common by the early 20th century that it had succeeded in becoming a commodity of its own. We also receive information about the lives of the people buying and writing on postcards. Where political history is lost, a more personal one is found.

Frequent mention is made of one’s health. The grandness of a monument scaled down to the size of intimate sniffles. But those two are connected. Illness or at the very least inconvenience brought on by the incompatibility with local environments was a feature in travellers’ diaries and letters. It comes up even in accounts of colonial officers who remained in India for decades. One could take the inscriptions of sickness as a quick and compact way of keeping concerned family or friends informed of their health; family or friends who would already have a perception of India as the destination of disease. Messages from the early 1900s like ‘I have a cold’ and ‘It’s too hot in Calcutta’ are not too far from texting, calling or posting on social media platforms today about the weather and its harshness. It is precisely the place being photographed that beckons the inscription of illness. For a person experiencing both at the same time, such postcards, although provoking slight humour today, make sense in their time.

There are more place-based postcards. A picturesque street view of Bombay comes with a father warning his children to not be fooled by the photograph on the card and that the city has a ‘dilapidated appearance’. Perhaps like X (formerly Twitter) and other mediums in contemporary times, postcards left little physical space for context. The author either didn’t know or was unable to elaborate on why certain areas in Bombay could be speckled clean, lush and leafy, and spacious with wide roads, elegant horse-drawn carriages like in the photo on one side of the postcard while others could be nothing of the sort. The various planned injustices of the colony and caste remain missing. Smaller place details come up in the text with schedules of trains to catch, or cities and towns and monuments being covered.

Postcards also worked as a sort of street photography and a way to document and catalogue native people. We come across visuals of ‘The Toddy Man’ with a man, presumably from a toddy collecting caste, up high on a palm tree, and ‘First Lady Cyclist’ of a woman who is either the first lady ever to ride a cycle in the subcontinent (a mighty yet unlikely feat to be archived) or the first Maharashtrian woman wearing a nine-yard sari, nath and bindi the photography studio captured sitting on a cycle. There are postcards of ‘poor Mahars’, a ‘Dancing Party’ from Chota Nagpur, a ‘Tamil Dancing Girl’ from Ceylon, ‘Indian pundits’ in Trinidad, a ‘Potter’, ‘Indian Hairdressers’ and others posed with the cloakings of their profession. An archive of caste. An elephant owned by the king of Jaipur too sees a young worker seated at the top as a possible mahout. This too is a proof of the structures of caste. The ‘royal’ postcard is priced at 13 rupees. For comparison, the average monthly wages of a carpenter in the latter half of the 19th century was less than that. One could see the lack of discomfort in purchasing such expensive yet objectifying cards, of people whose likeness they may have seen but who were specifically unknown to them, for loved ones. The detachment and alienation engendered when photos are commodities, reducing the people in them to peripheral parts of your tourism, and their frames serve merely as margins to note your life in. But then again, what is the difference between posting through courier or Instagram? Colonial impulses remain in the language of photography itself where you ‘capture’ a person after ‘shooting’ them.

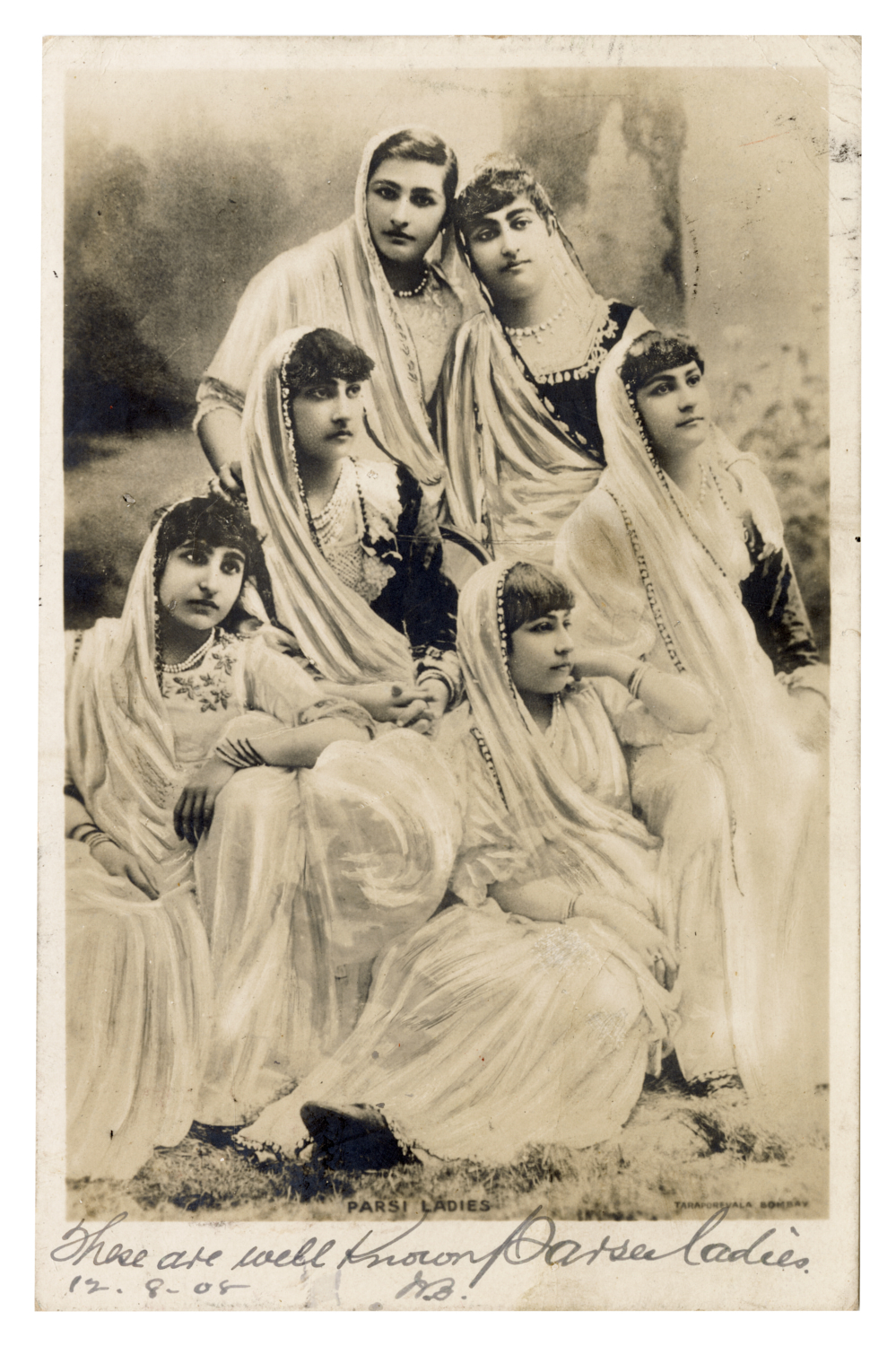

The exhibition also curates the more intriguing stories of postcards. Embellished ones decorated by women as a social or religious activity. Studio portraits of Parsi women who channelled photography as a ‘marketing strategy’ for their small yet politically important community. A postcard of Delhi’s India Gate from 1930 has the rare voice of a child speaking to their father. Another, this time from a father to his son, features a dancing girl. How puzzling that a profession deemed ‘lowly’ by the British and dominant classes of natives was fit enough for a message to his child.

Stories are scribbled on the walls and tables of Hello and Goodbye: Postcards from the Early 20th Century. These postcards open up a range of possibilities to closely look at the lives of people moving within and viscerally experiencing a colony. The words of travellers, of those with the means to travel, of silenced sometimes smiling figures, and of the relationships they carried between them. There is a rich body of knowledge present between postal lines that detail anecdotes at times related to what you see on the other side, and other times ignorant of it. Because what truly matters is everything that comes between a simple hello and goodbye.