Blogs

What Is New Media?

Girinandini Singh

Traditionally when we think of art we think of paintings, sculptures, oils, drawings, charcoals, screen-printing, and more recently photography. So what really is ‘new media’ art?

Traditionally when we think of art we think of paintings, sculptures, oils, drawings, charcoals, screen-printing, and more recently photography. Our inherent understanding of what makes art is via its medium. The medium is a tool of creation and expression, but also one of definition. It is through its organised framework that we find some semblance in our reading of creative expression; an orderly attempt to chalk the boundaries of what makes something a work of art. Defining art via its medium is a necessary measure if we are to seek any sense of uniformity or organisation when dealing with the abstract world of ideas, notions, and philosophies. And yet, with the ‘medium’ evolving faster than its framework, we run against problems of scope, definition, boundaries and interpretation into the murky territory of fluid boundaries and infinite possibilities.

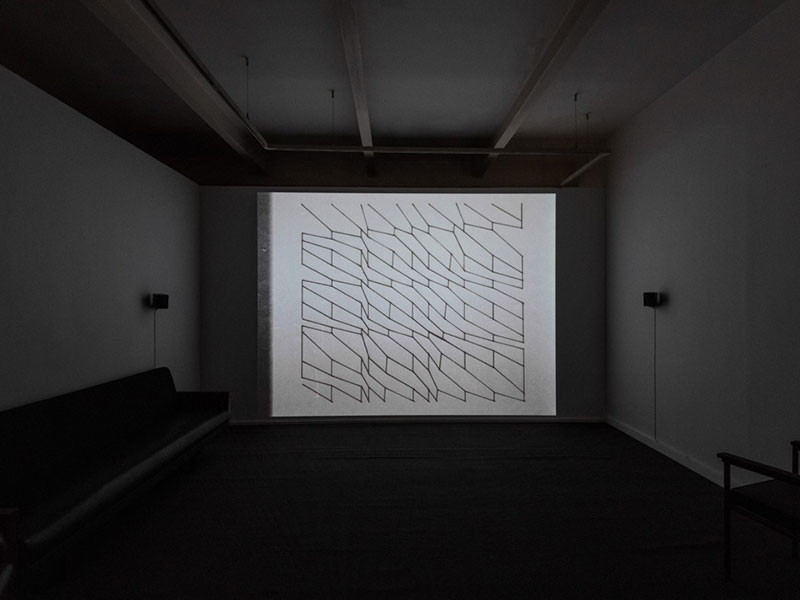

What we think of New Media today is essentially what was once called Digital Media Art. The usage of the term New Media simply widens the scope of its territory to include pieces such as interactive installations, hybrid digital and physical sculptural art, coding, machine learning or mixed media works. The medium has slowly and continually evolved over time alongside the leaps and bounds of technological advancement. Think of Warhol and his usage of the blotted-line technique to mask the evidence of hand drawings in the 50s, printing his work at mass from photographs in the 60s, and using the Norelco Carry-Corder to record conversations and sound for soundscapes in his films – these were all early pieces of evidence of what we call new media. Closer to home in India, between 1969-1972 Akbar Padamsee was experimenting with the visual medium as an enhancement to his paintings. He created two short films as part of the Vision Exchange Workshop in Bombay, and out of the two, one remains as a dated VHS tape titled Syzgy. The stop-motion animation video showed a variety of dots, lines, and shapes, denoting the philosophical idea of a union among opposites. The second film, now misplaced, was called Events in a Cloud Chamber and used light to recreate one of Padamsee’s paintings; a detailed and moving experimentation in the mixed medium at the time. Today, when we look at New Media it is defined as a genre of artworks created with digital technologies ranging from film, computer graphics, interactive videos, installations, virtual art, animation, to robotics, art as biotechnology, and 3D printing.

Syzgy, Akbar Padamsee, 1970, Image Courtesy: Jhaveri Contemporary

In contemporary art the penetration of New Media has been a continuously ongoing process, if somewhat subconscious; as technology matured, artists began experimenting with it and integrating it within their creative processes in a completely organic format. Take, for instance, video art and installations: using the popular medium of photography and film to create immersive environments is perhaps the most common understanding of new media art. The moving image’s instantaneous ability to arrest and magnify experience is why there is such a close link between video works and installation art. Consider L. N. Tallur’s Interference which is a slow-motion video lasting a little over four minutes of an antique carpet dusted by two museum workers. The carpet is two centuries’ old and tied to the colonial history of India. The dust released from its rigorous beating is a form of accumulated evidence of the passage of time, the historic struggle of the nation (royalty, ministers, maharajas have walked on the bright green floral design), and as it cascades down onto the diligent workers it seems minimised to the industrious routine of the every day and the ordinary. The poignancy of the work is derived not as much from the subject matter as it is from the technology which provides a complete immersion into the significance of the piece across time. It becomes the most obvious space for questioning the transformation, which occurs during the live-action and its rendition afterwards.

Interference, 2019, 4k video, television monitors. Courtesy the Artist and http://tallur.com. Interference was made in partnership with the Junagadh Museum in Gujarat, India. Special thanks to the Junagadh Museum; Varia Kiran, Videography; Vandita Jain, sound engineer; and Bhanu Pratap Singh

With New Media, however, comes a fair amount of experimentation and playful contemplation on the nature of art itself. An example is the process-oriented work of visual artist Sareena Khemka, who uses found objects, technology and bio-art to create cityscapes: a meditation on both, the creative experience as well as the significance of the medium building it. Khemka plays with perspective, space, and abstract cartography creating sculptural cities with fragile and temporal materials from the physical environment like cultivated bacteria cultures. Bio-art, a more current and untapped niche, is one among the numerous areas of investigation that the continuous flux of the genre brings. Among the arising lines of questioning as New Media develops, is if being technologically vanguard is sufficient for artists to attain repute and credibility for their work? Is mastering digital and technological tools to create aesthetically pleasing work enough to consider it as art? These questions raise a discursive conversation between the role of the artist overlapping with that of the technological medium, where does one end and the other begin?

Girinandini has a Masters in Creative Writing from Newcastle University, UK. She has published with literary magazines like Prufrock, Waccamaw; a journal of contemporary literature, and Litro Magazine. She writes for Outlook, Vogue, Architectural Digest, STIRWorld and Critical Collective.