Blogs

The Photographic Journey of India

Prachi Gupta

Given the expanse of the photography genre in India, as researchers we often wonder how one can really chart the journey of the medium. Here’s a brief history of the evolution of Indian photography, from the colonial rule to present times.

Arriving as early as the 1830s owing to colonisation, the genre of photography in India has been flourishing for over 170 years. Given the expanse of the medium and the vast period of time, as researchers we often wonder how one can really chart the history of the medium? What are the factors that have defined what was photographed, which further poses questions about representation, influences and access? The exhibition at Monash Gallery of Art, Melbourne, Visions of India: From the Colonial to the Contemporary aims to trace this very journey, by roughly dividing the timeline in three parts – Photography in the Colonial Era (1850s-1947), Photography after Independence (1947-1990) and Contemporary Photography (1990-2021), presenting visual examples from each segment that defined the major trends of the time. Showcasing photographs from MAP’s vast collection, it seeks to prod the viewers to re-examine the photographs by the scales of the social, political and cultural timelines in which they were created, looking beyond what meets the eye.

Each time segment is defined by major historical phases in the evolution of the country and its people. From being under colonial rule, to building itself up as an independent nation, the history of photography in India is directly tied to these factors.

Photography in the Colonial Era (1850s-1947)

In its early years, photography catered to the rich, the royal and the ruling. An expensive medium in exploratory stages, it was accessible to only a few, which influenced the subject of what was being produced. The British colonists judiciously turned photography into an imperial tool, using it to document the land, the colonised people and sometimes banal or significant events during their reign, for instance, the site of the 1857 revolt by photographer Felice Beato.

Bailey Guard by Felice Beato, 1857, Albumen print, PHY.07193

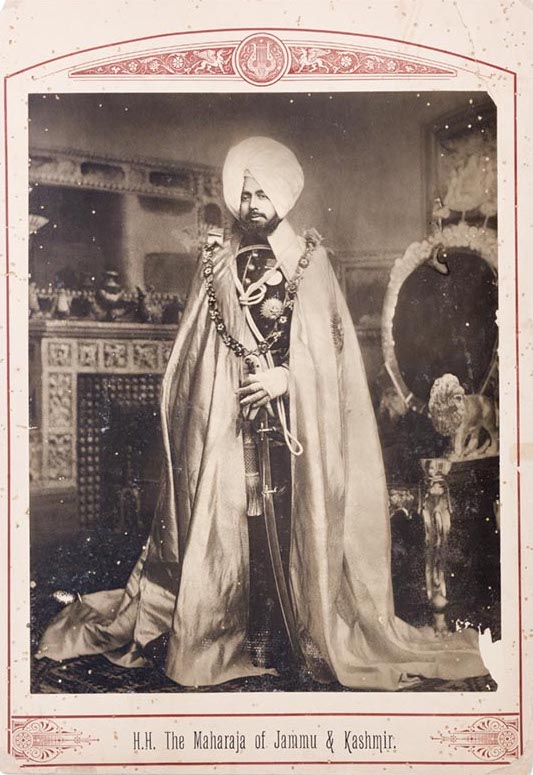

Photography for them also became the medium to understand political favour, recording those who showed allegiance, which is reflected in works such as the Princes and Chiefs of India by Lala Deen Dayal, and those whose allegiance they wished to understand, as seen in the eight volumes of People of India, in which the subjects are analysed by physical and behavioural characteristics. Several photo studios were set up in major British presidencies during this period that played a large role in propagating views of the far-away exotic land and its natives within England, satisfying the curiosity of those back home.

H. H. The Maharaja of Jammu & Kashmir by Lala Deen Dayal, c. 1900, Possibly carbon print, PHY.00085.AP

Interestingly, it was around the same time that the Indian royalty also took to photography with equal enthusiasm, largely as patrons and sometimes as amateur practitioners, as seen in the works of Sawai Ram Singh II. By the 1920s, photography still existed within the strict quarters of European portraiture, albeit slightly more accessible to people owing to the opening of studios across the subcontinent. Artistic forays parallel to popular aesthetic movements of the time like pictorialism (an international aesthetic movement in photography from the late 19th and early 20th century that emphasises beauty of subject matter, tonality, and composition rather than the documentation of reality) were mostly unknown by Indian photographers, except for rare names like Shapoor N Bhedwar.

Portrait of a Courtesan, Sawai Ram Singh II, Maharaja of Jaipur, c. 1860, Albumen print, PHY.12341-16

Photography after Independence (1947-1990)

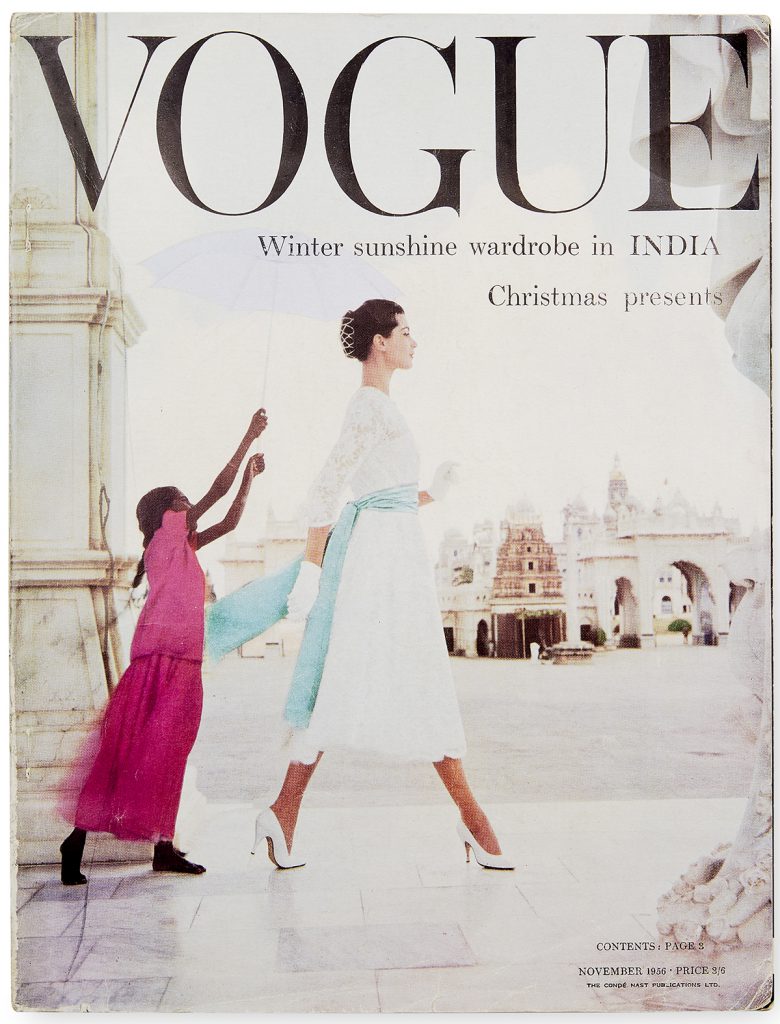

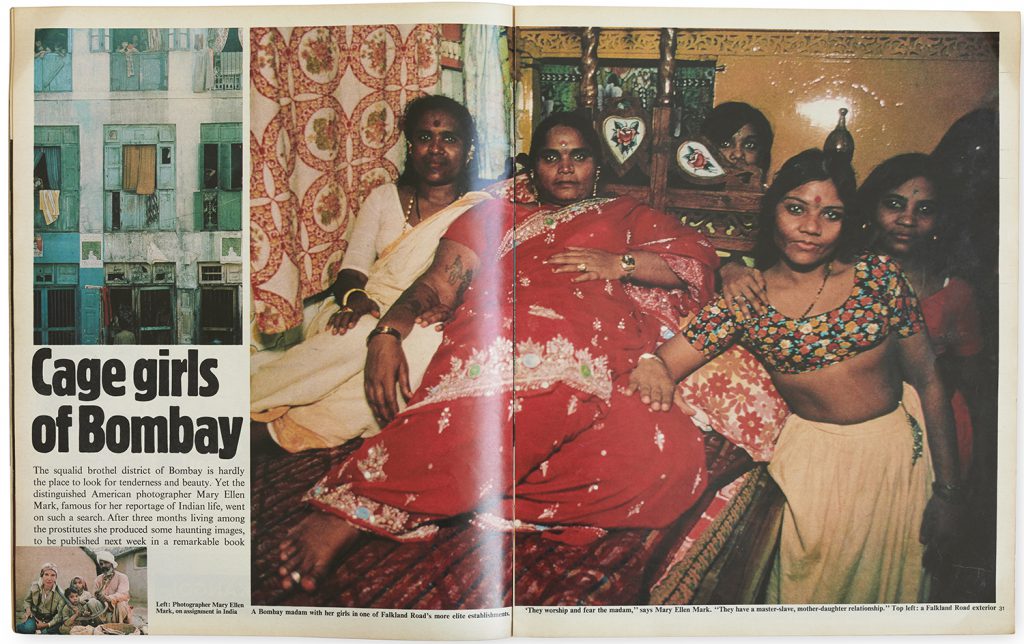

By the time of Independence, Indian photography was still trying to find its hold amidst a hangover of colonisation, balancing influences from the West while trying to forge its own artistic sensibilities. Although several western photographers were still portraying India as a mystical, vibrant, exotic land, untouched by modernity, as seen in the works of Norman Parkinson (British Vogue, November 1956), Steve McCurry or Mary Ellen Mark (Falkland Road, Sunday Times Magazine), there were a few Indian photographers who were focusing the light elsewhere.

British Vogue magazine cover by Norman Parkinson, November issue, Offset print (entire magazine), 1956, TC.636

Spread from The Sunday Times magazine by Mary Ellen Park, Offset print (entire magazine), May, 1981, TC.638

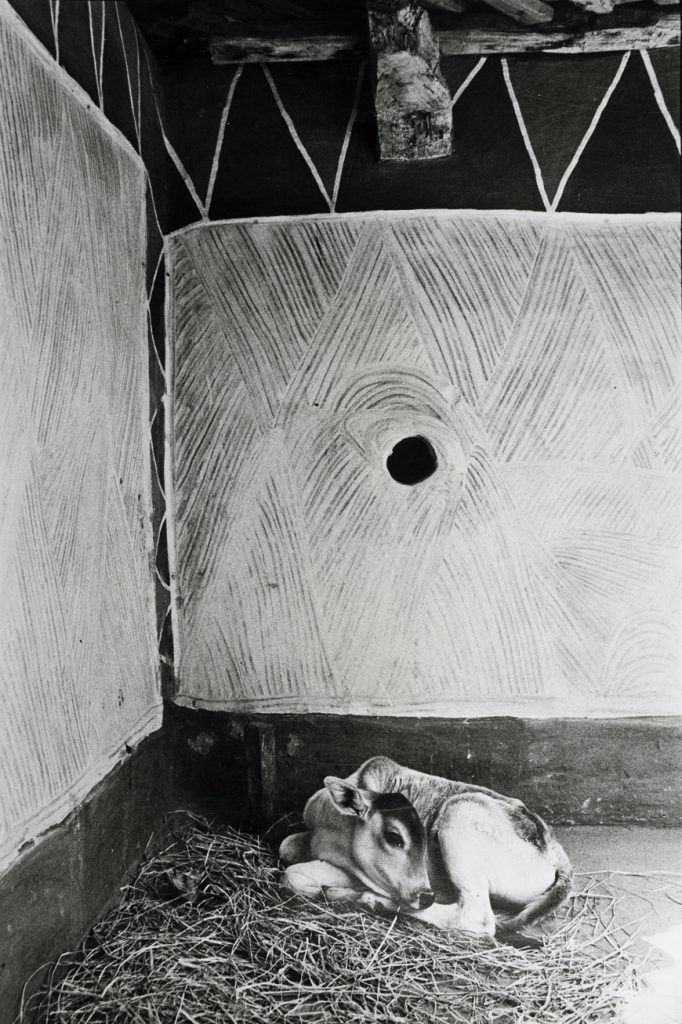

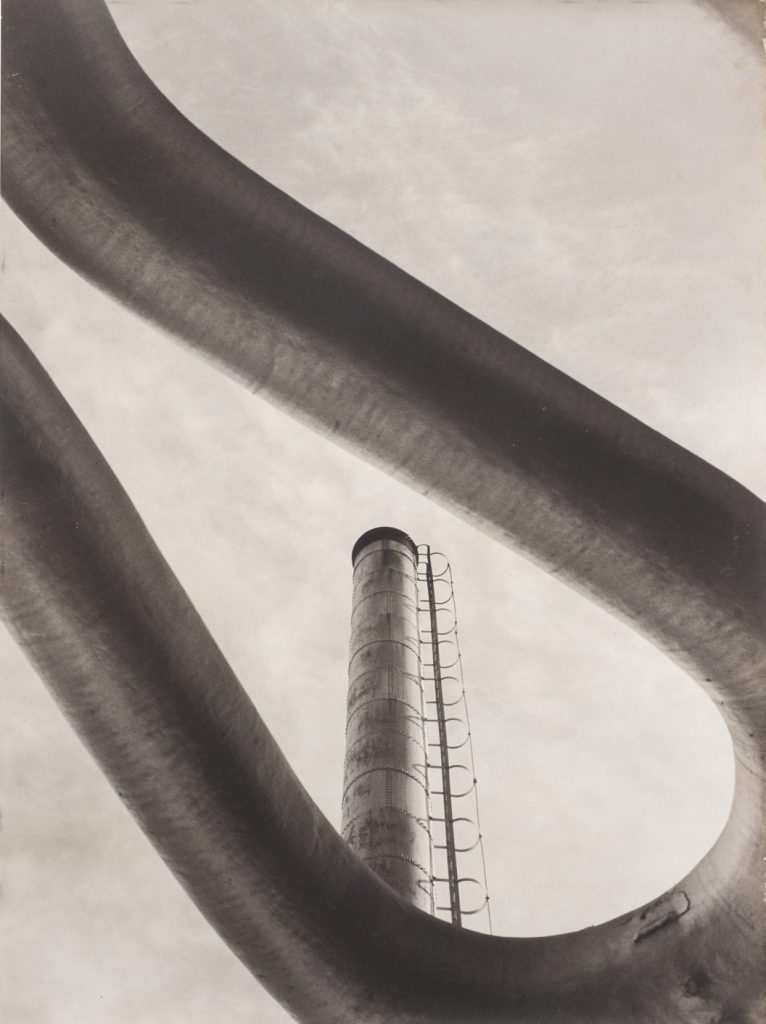

Modernist Jyoti Bhatt, for example, compiled an extensive photographic documentation of the rich living traditions of India, combining modernist sensibilities with local culture. Mitter Bedi, one of the first advertising photographers of India, took glorious images of the fast-growing industries and architecture of the country. At the same time, the work of studio photographer Suresh Punjabi showcased photography at the grassroot level, providing a space to the locals of a small town in Madhya Pradesh for expressing and exploring themselves.

Rajwar tribal house at Sarguja Dist., Madhya Pradesh by Jyoti Bhatt, 1983, Silver gelatin print, PHY.00393

Hindustan Lever Pipeline to Progress by Mitter Bedi, 1961, Silver gelatin print, PHY.12272

Contemporary Photography (1990-2021)

The contemporary timeline is definitely one to look at, where one can see artists exploring new meanings through the medium. With a completely different set of views and a new line of thinking, photography is today being used as a medium of expression and a tool to question concepts such as the self or post-colonial identities, while also addressing personal traumas and the politics of gaze.

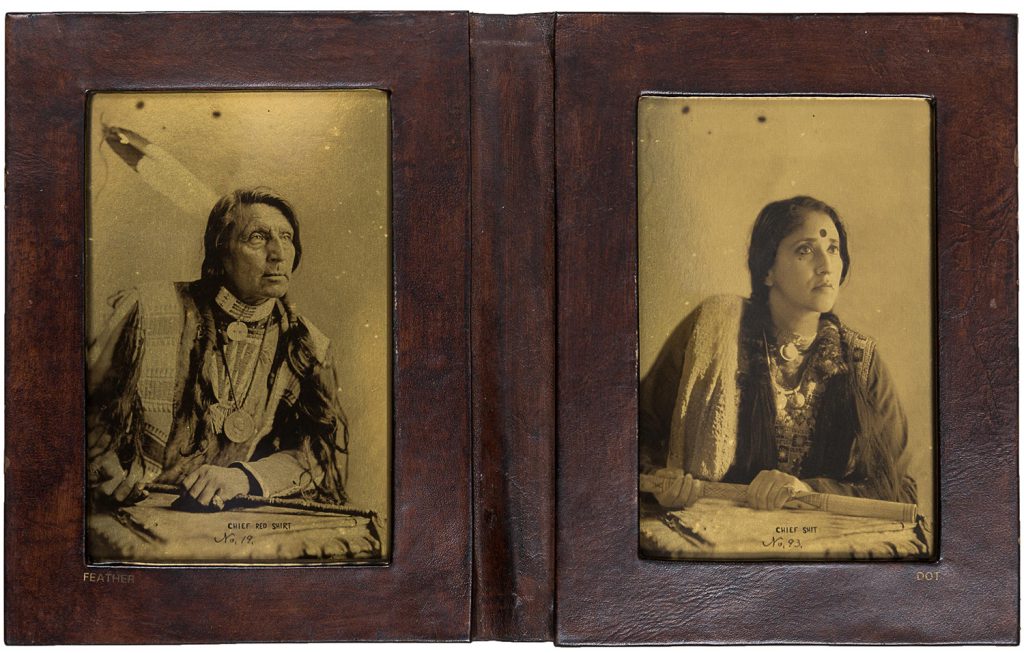

Feather Indian/Dot Indian by Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, 2007-2009, Digital orotone in leather album, PHY.03939-1

Whether it’s photographers of the Indian diaspora, like Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, who seeks the answer to her identity as an Indian immigrant in America through her work An Indian from India, or Indian photographers like Indu Antony, who addresses personal trauma through her work Vincent Uncle, new age contemporary photography in India is pushing away its far-set stereotypical image, and moving towards becoming a more nuanced medium of expression.

Vincent Uncle (01 of 21) by Indu Antony, 2017

Each photograph from the 170+ works displayed in the exhibition opens a visual enquiry into the history of the country’s evolution, developments in the medium and changing norms of photographic expression. Click here to take a virtual tour of Visions of India: From the Colonial to the Contemporary and explore the breadth of Indian photography for yourself.

Prachi Gupta is an Archivist in the Photography Department at MAP. Her artistic interest lies in history, archives and performance. An amateur ukulele player, she likes trekking, tattoos and tasting new food.