Blogs

The Melting Pot: Parsi Cuisine

Girinandini Singh

As a community the Parsis were known for their philanthropy, traditions, and values of educating, but most of all for their food and culture. Read about the role of Parsi food in the ever-changing cultural landscape of Mumbai.

The Parsi community with its roots in the Persian Empire, were followers of Zoroastrianism, an early monotheistic religion believed to have been revealed some 3,500 years ago. It was somewhere in the late 9th and early 10th century that the Parsis, as they came to be known in India, landed on the shores of Gujarat. Raja Jadi Rana granted them sanctuary in Diu on the condition that they wouldn’t force their faith on the people of Gujarat, nor cause any unnecessary turmoil and live their lives peacefully. It was the beginning of a long history of Zoroastrianism existing parallel to the many faiths of India, and it continues even today as a living religion with a vibrant community of Zarathustis practicing it all around the world.

As a community the Parsis were known for their philanthropy, traditions, values of educating and giving back, but most of all for their food and culture. Sadly, one of the greatest challenges faced by the community today is the preservation of this very way of life, of their traditions, living faith, and a culture that has mingled to become part of the building blocks of a post-independent India.

Parsi Lady by M. V. Dhurandhar, 1928, Watercolour on paper, Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

When I think of Parsi food it is almost impossible for me to not conjure up a beautiful mirage of the “perfect Bombay experience”. Memories of an early visit to the city come to mind, of being guided by my mother’s own reminiscences of working there as a young advertising director, rushing through a day’s work intercepted by masala chais, bun maskas and lunch at Britannia & Co. While Parsi food is by no means limited to the city of Mumbai it is most certainly a consistent part of its ever-changing cultural landscape.

Levi-Strauss (1969) has stated that our food – its preparation and consumption – marks the human journey from nature to culture. Food thus, becomes an emblem of ethnic identity, of civilisation, class, caste, and more, a notion that is brought out delicately in MAP’s latest exhibition – Stories on a Banana Leaf. Within the Parsi community in particular, food has often been used to create a community identity through its interactions with other communities. It has been the great equaliser, a medium by which it created a place for a culture to thrive outside the limits of its own community.

Yaazdani Restaurant and Bakery, an Irani cafe in Mumbai, Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The Irani cafes of Bombay perhaps make for the best examples. Growing to their height between the 1930s and 1960s, and frequently cropping up across the city’s many street corners welcoming all who cared to visit them. These significant sites became shared spaces for inter-cultural interaction, in what was a largely segregated 19th century Bombay, which despite its cosmopolitanism was still restricted by certain traditions set in place by the British.

Where the Yacht Club and the Bombay Gymkhana Club refused to allow in Indians or people of colour, the Irani cafés opened by immigrants subverted such biases, setting in place a counter-cultural movement of tolerance and democratic change. Here, the meals were cheap and sustainable, and a few paise took one a long way. As early examples of the city’s first public eating spaces, these shared sites led to shared experiences fostering an inter-communal tolerance that broke down pre-existing barriers of segregation.

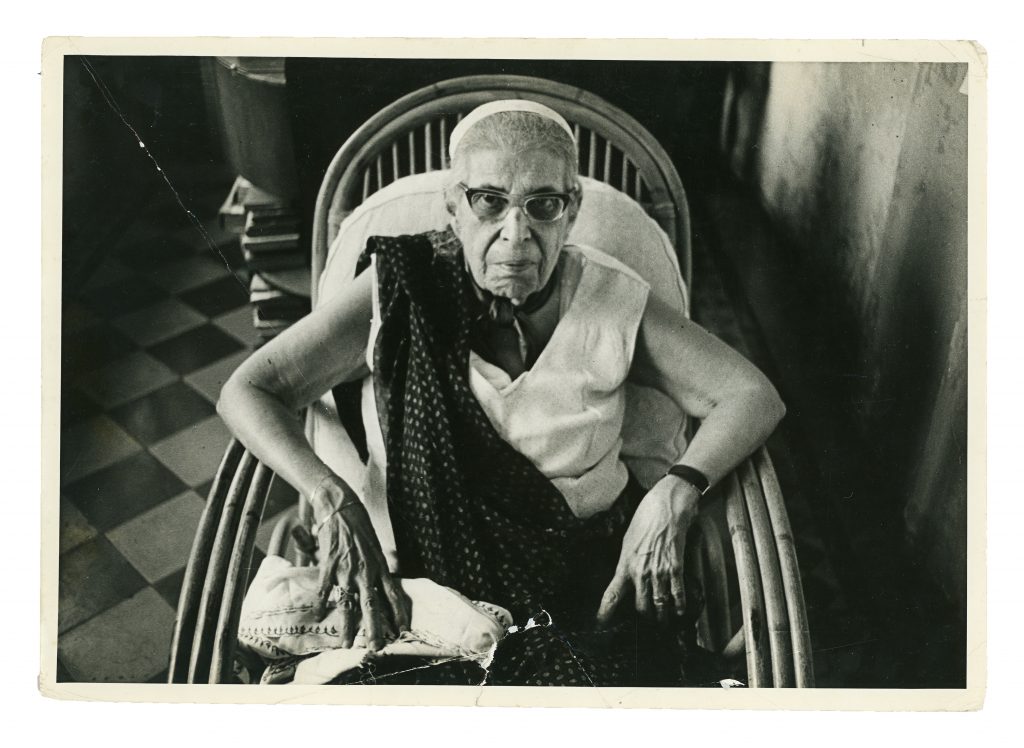

Parsi Lady, Hong Kong by T.S. Satyan, 1970, Silver gelatin print, PHY.10341

Interestingly, Parsi cooking has been shaped by the co-mingling of two separate traditions. One stemming from their roots in Persia and the other from their adopted home in India. The unusual mix gives Parsi food its unique flavour palate where nuts, dry fruits and the use of shirni (sweet) comes from their ancestral home in Persia, and adopting garlic, ginger and chillies has been a homage to their place in India. The perfect Parsi dish, I’ve been told, is in fact one that combines the essence of all these flavours i.e. spicy, sweet and sour. It is not too different from a community which strives to bring everyone together to the dining table, creating a comfortable balance between the personal and the communal.

Girinandini has a Masters in Creative Writing from Newcastle University, UK. She has published with literary magazines like Prufrock, Waccamaw; a journal of contemporary literature, and Litro Magazine. She writes for Outlook, Vogue, Architectural Digest, STIRWorld and Critical Collective.

References

RAGHAVAN, ANIRUDH, et al. “Circuits of Authenticity: Parsi Food, Identity, and Globalisation in 21st Century Mumbai.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 50, no. 31, 2015, pp. 69–74. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24482166. Accessed 5 July 2021.

THAKRAR, SHAMIL; THAKRAR, KAVI; NASIR, NAVED; Dishoom: The first-ever cookbook from the much loved Indian restaurant; Bloomsbury Publishing, Illustrated Edition, 2019.

FERNANDES, NARESH; City Adrift: A Short Biography of Bombay, Aleph Book Company, 2013.