Blogs

The Alchemist: Jamini Roy

Shubhasree Purkayastha

An average Bengali household in any part of the world is likely to have three things in common – a portrait of the Vaishnava saint Ramakrishna, one of his disciple Vivekananda and a painting by Jamini Roy. Learn more about one of India’s foremost modernists!

“Peace is not good for an artist. How can that happen? The mind strives and burns all the time in the creative activity of art.”

– Jamini Roy

An average Bengali household in any part of the world is likely to have three things in common – a portrait of the Vaishnava saint Ramakrishna, one of his disciple Vivekananda and a painting by Jamini Roy. One can imagine this arrangement suiting the artist rather well for Jamini Roy, one of India’s foremost modernists, was a life-long advocate of making art accessible to the masses. Today, he is recognised not only for his contribution to the revival of Bengali folk art but also for transforming these traditional idioms into one of India’s earliest indigenous modernist visual expressions.

Early Years

Interested in painting since his childhood, Roy moved to Calcutta in 1903 from Beliatore village in Bankura district, West Bengal, to study art. Here he enrolled in the Government College of Art and was trained in the prevailing western classical tradition by illustrious artists like Abanindranath Tagore. After graduating from college with a diploma, Roy began to take commissions for landscape and portrait paintings. These early works in the post-impressionistic style showcase excellent draughtsmanship and control. During this period, he also regularly copied well-known European works of art as practice and to further hone his skills.

A Paradigm Shift

In the early 1920s, however, Roy grew dissatisfied with what he was doing and went back to his village looking to experiment with his style. Here in the village, a unique visual vocabulary confronted him – one that he had grown up with and was vastly different from what he had encountered in the art school and the city art circles. From the alpona (ceremonial decoration made with rice-paste) drawn on the floors to the terracotta statues of Bishnupur, Roy found inspiration everywhere and slowly began to appropriate these folk idioms into his art practice.

His biggest influence, though, were the patuas of Kalighat and their incredible watercolours, now recognised as a unique form and referred to as Kalighat painting. He was so struck by them that, later in life, he would refer to himself as the ‘urban patua’. The patuas were originally scroll painters and itinerant storytellers who moved to Calcutta to sell souvenirs outside the Kali temple at Kalighat. These were quickly drawn, cheap watercolours on thin paper, usually depicting religious icons and mythological stories.

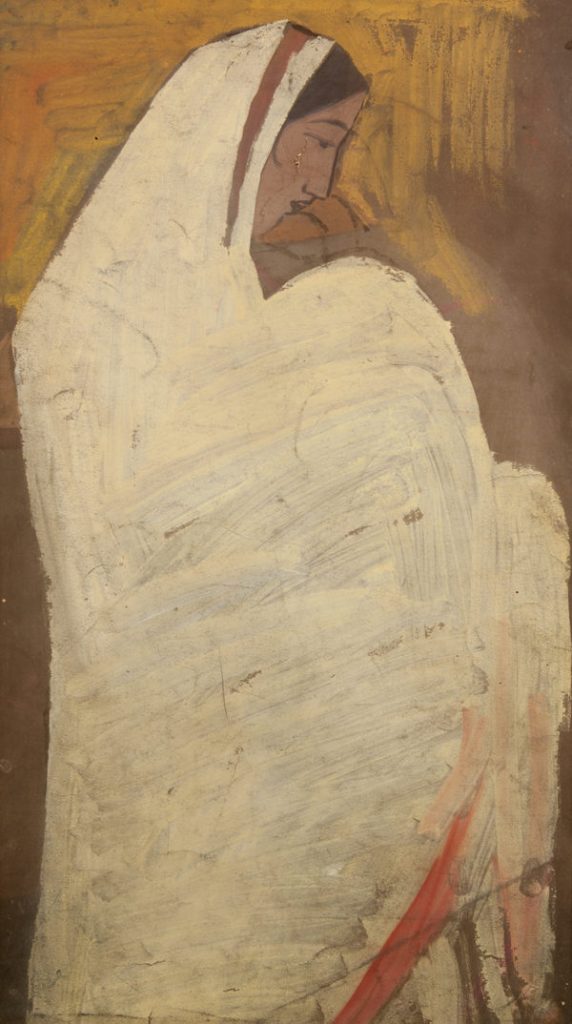

Over the years, Roy completely discarded his earlier practice to arrive at a unique and minimalist style marked by simplified forms, fluid lines, flat application of colours and the discarding of non-essential background details. Roy’s lines, although derived from the sweeping brushstrokes of the patua painters, were more restrained and calligraphic. This enabled him to create sophisticated and lyrical forms, highlighted by almond-shaped eyes which became another signature of the artist’s works.

“It’s about the simplicity. Here is a man who, with just two or three brush strokes, can create this beautiful woman sitting with her hand on her knee, gazing out from under her sari. The absolute simplicity of a few brush strokes—that is the mark of a genius.”

– Kishore Singh

Experimentation With Mediums

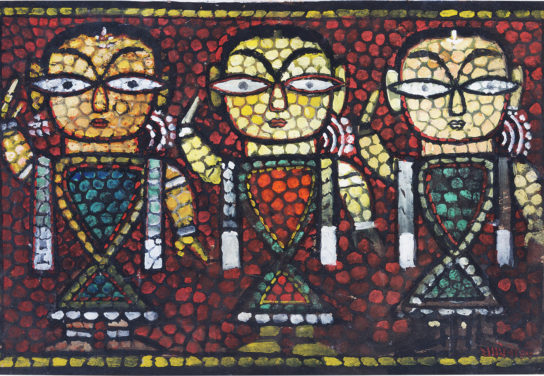

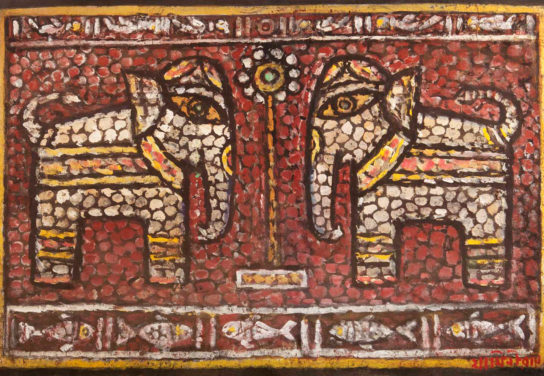

As with his artistic style, Jamini Roy began to reinvent his materials too – he produced his own colours from nature and created canvases using cotton and wood. A unique material that Roy experimented with at this time was the woven mat made of bamboo grass (locally called the choti). The inspiration for this experiment came from examples of Byzantine Art that he had seen in photographs and it occurred to him that painting on a woven mat might create a similar mosaic-like effect. This was to become a recurring form seen in a range of artworks – sometimes even on flat canvases where the mosaic-like texture was rendered with painted lines.

Major Themes

In a career spanning over fifty years, Roy experimented with a variety of themes and subject matter. What began as curiosity towards simple rural living, continued to evolve and encapsulate themes across regions and religions. His subjects ranged from depictions of village life (especially the Santhal community), animals and birds to local folklore, religious mythology and even social satire – all rendered in the style that had by-now become synonymous with his name.

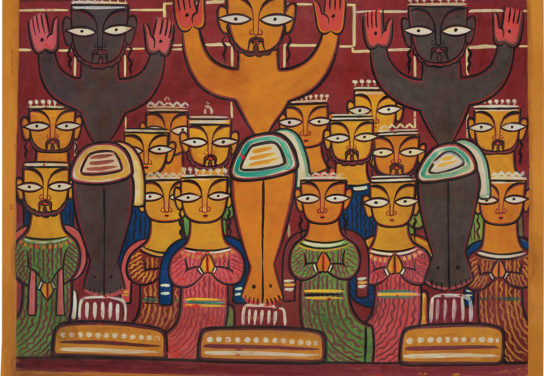

From the 1940s, Roy began to show interest in Christian mythology. Somewhat preoccupied with this singular theme, he produced canvas after canvas centred on the life of Christ. Collectively known as the ‘Christ Series’, what is striking about them is how Roy took a subject that was more or less alien to him and gave it a local, earthy feel. The compositions, though religiously solemn and grave, are invested with a kind of vibrancy and playfulness. His characters, even when borrowed from age-old epics, seemed reassuringly familiar and relatable.

Making Art Accessible

For Jamini Roy, interest in the indigenous ran deeper than just the emulation of its form and style. He modelled his entire artistic process upon that of an indigenous artisan. This meant making version after version of a single object, creating multiple copies of the same work and turning his family into a production unit much like the craft-guilds. This model of ‘factory-production’ also made his art accessible to everyone. Seeking equally to be affordable to those he believed were the real subjects of his work, Roy is said to have always sold his art at extremely low prices, sometimes even gifting it away.

Jamini Roy died in 1972 at the age of eighty five. A recipient of the Padma Bhushan (1955), he was posthumously honoured with a commemorative stamp by India Post in 1978. He is also recognised as one of the country’s nine National Treasures (as per a rule passed in 1972 under the Antiquities and Art Treasures Act) which forbids the sale of his work outside India. Today, Roy’s art is displayed in hundreds of museums and galleries and often sold for large sums, which he would have certainly disapproved of. However, most importantly, it lives on as one of the most recognised styles of Indian modernist art, appealing in equal measure to children and art connoisseurs, and in some form or the other in people’s households as part of their everyday lives – just the way he would have wanted it to be.