Blogs

Serpentine Tales

Shilpa Vijayakrishnan

Animals have always been powerful symbols – in religious traditions, nationalist narratives, as storytelling devices, popular emojis and a myriad of other instances.

Animals have always been powerful symbols – in religious traditions, nationalist narratives, as storytelling devices, popular emojis and a myriad of other instances.

The snake is one of the oldest and most widespread of mythological symbols. And although it’s received a fairly bad reputation for being a slithering, slinking and sly creature (deceiving Eve into eating the forbidden apple, for instance), there are many layers to its symbolic associations. In many cultures, from the Greek to the Indian, it also represents rebirth and renewal, due to the fact that it sheds and regrows its skin.

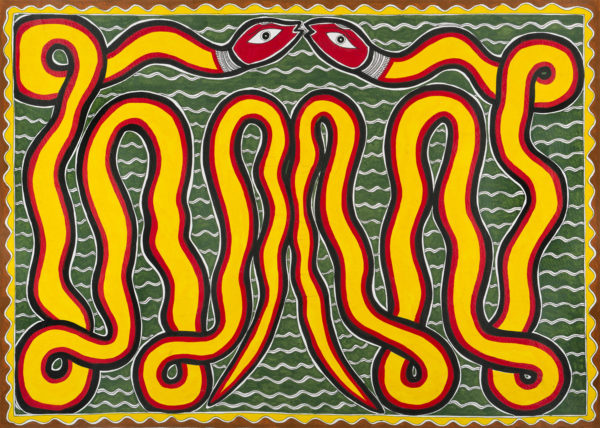

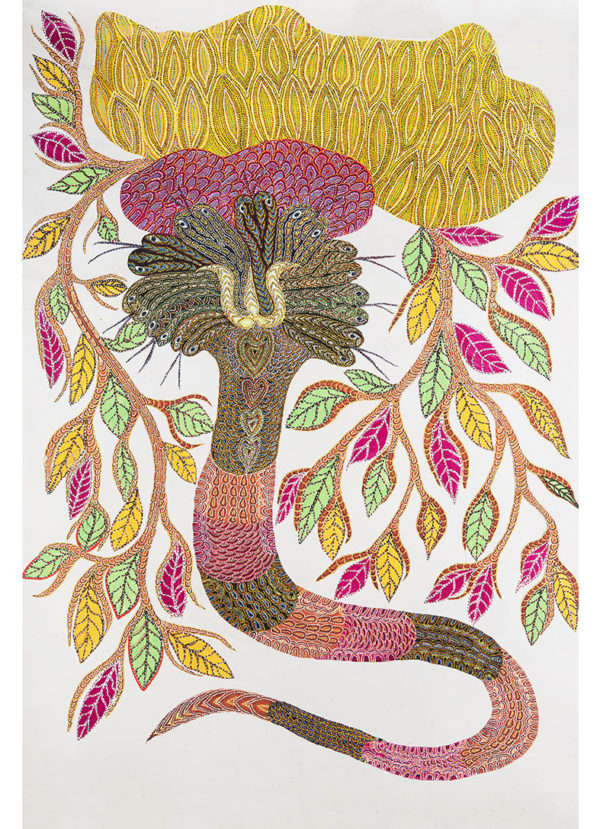

Snakes are common subjects in the folk and tribal arts of the subcontinent, reflecting traditions of snake worship as well as the communities’ close connections to nature. Many Indian folk narratives often represent snakes as both deadly and beautiful, objects of fear as well as love, poisonous but also loyal.

A Madhubani or Mithila painting by Baua Devi featuring Nag and Nagin, Ink and watercolour on paper, 2005

A Gond-Pardhan painting by Jangarh Singh Shyam titled Ajgar (python), Poster colour on paper, 1992

Anand Shyam, Magar Aur Saap (crocodiles and snake), Poster colour on paper, 1997

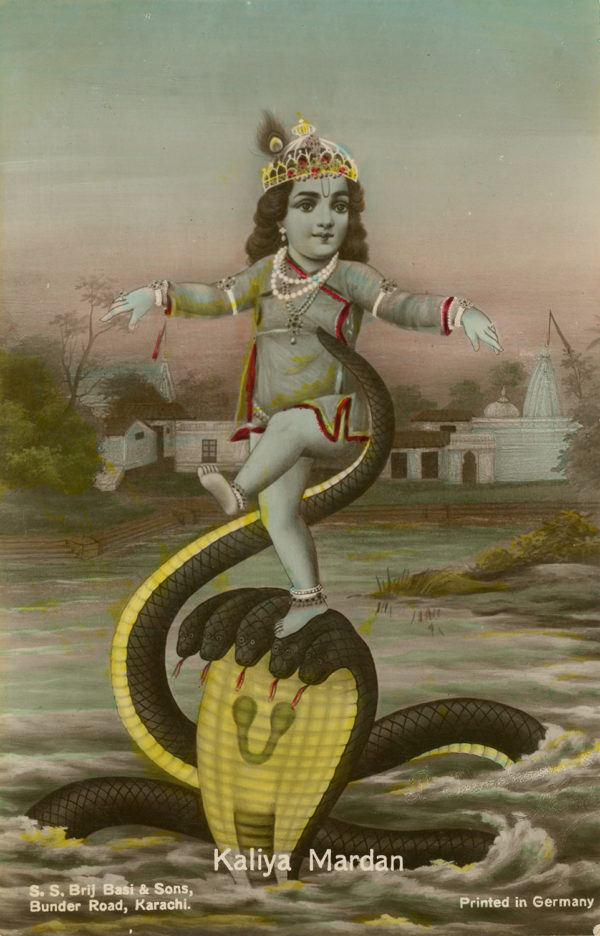

Snakes are also extremely prolific in Hindu mythology, taking on roles both good and bad. There’s Ananta Shesha, the primordial being upon whom Lord Vishnu rests, who holds the universe upon his hood and all of creation and time in his coils. He is also sometimes referred to as the first king of the naga people, a semi-divine race of half-snake half-human beings, believed to reside in the underworld. On the other hand, there’s Kaliya, the naga who turned the Yamuna into a frothing, bubbling river of poison, until he was defeated by Krishna who danced him into submission!

A stencil depicting Sheshshayi Vishnu that depicts Shesha as an uroboros, or a full circle symbolising wholeness and infinity, Paper, c. 1870

Jangarh Singh Shyam, The serpent Shesha holding the earth on his hood, Poster colour on paper, Late 1980s

Postcard depicting Krishna dancing on Kaliya and subduing him, Chromolithograph, early 20th century

The nagas also feature in the origin stories of Garuda, the vahana (or mount) and emblem of Lord Vishnu. It is believed that Garuda’s mother, Vinata, mother of the birds, was tricked into becoming the slave of her sister and co-wife, Kadru, mother of the nagas. The lasting enmity between the birds and serpents is attributed to this, and Garuda is considered to be the mortal enemy of all snakes. It is therefore, not uncommon to find depictions of Garuda with snakes between his claws or beak, or occasionally even draped around him like a garland – symbolising their subduing at his hands.

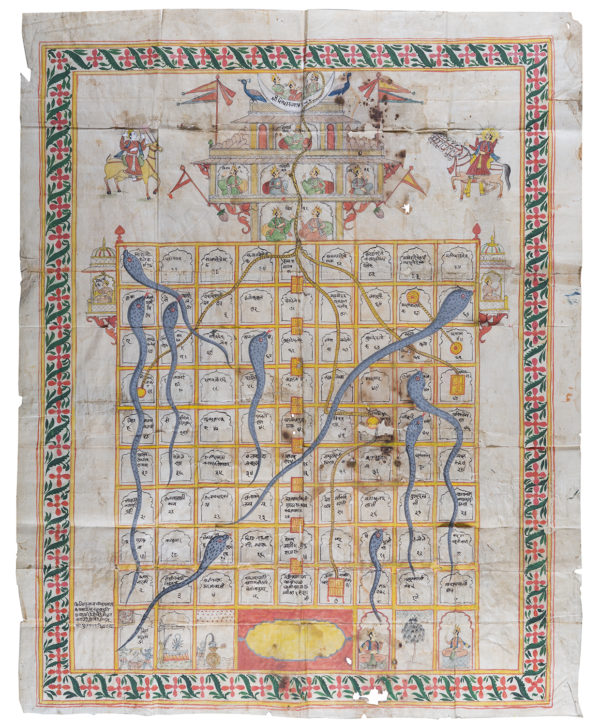

Among deities who sport serpents as ornaments though, nobody can really beat Shiva. The cobras—seen around his neck, upon his head, or serving as armbands and belts—are sometimes interpreted as symbolising endless time, fertility and regeneration. At other times, they are seen as representing the ego, fear and ignorance that Shiva has vanquished. The association of snakes with vices is also what prompts their role in the traditional gyan chaupar, or its modern day equivalent of snakes and ladders!

Garuda vahana, Painted wood, c. 1920

A prabhavali or decorative arch designed as a seven hooded serpent, meant to be placed around the shivling in a temple, Bronze, c. 1780

Gyanbazi (game of snakes and ladders), Opaque watercolour on fabric, late 19th century

Although an India filled with snake charmers who do rope tricks remains an exoticised Orientalist representation of the country – and there are few snake charmers to even be found today – our visual imaginations and collective stories remain enamoured of serpents. To such extent, that they sometimes make unexpected appearances in artworks that aren’t really about them at all. Here’s a painting depicting the Jatayu Vadh (slaying of Jatayu) scene from the Ramayana. In it, the painter seems to have included a unique subtext with two unidentified animals and a snake, seen at the bottom, trying to thwart Ravana by biting him as he strikes. Doesn’t that just turn all that eternal bird-snake enmity on its head?

This multiplicity of meanings, ranging across the dual notions of good and bad, is perhaps what makes the representation of snakes through time and mediums so fascinating. We are presented with more than one side of the coin – or rather we shed layers of meanings even as we grow new ones – each time we encounter a snake in art.

A painting depicting the Jatayu Vadha, Opaque natural pigments on paper, c. 1850