Blogs

Painted Stitches, Woven Stories

Arnika Ahldag & Vaishnavi Kambadur

The special case of kanthas in the museum space and speculation as a mode of curating.

MAP has a vast collection of textiles from Bengal, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Punjab and most regions of the Indian subcontinent. This includes silk brocades, phulkaris, bandhanis and kalamkaris. Once the costumes and textiles enter the collection of a museum, and that too an institution that represents visual culture, it is easy to notice the special case of kanthas. What fascinated us are the stories that these textiles tell, of the makers and keepers, especially from the Bengali region of the sub-continent, which is today the eastern region of West Bengal, Bihar, Orissa, and Bangladesh.

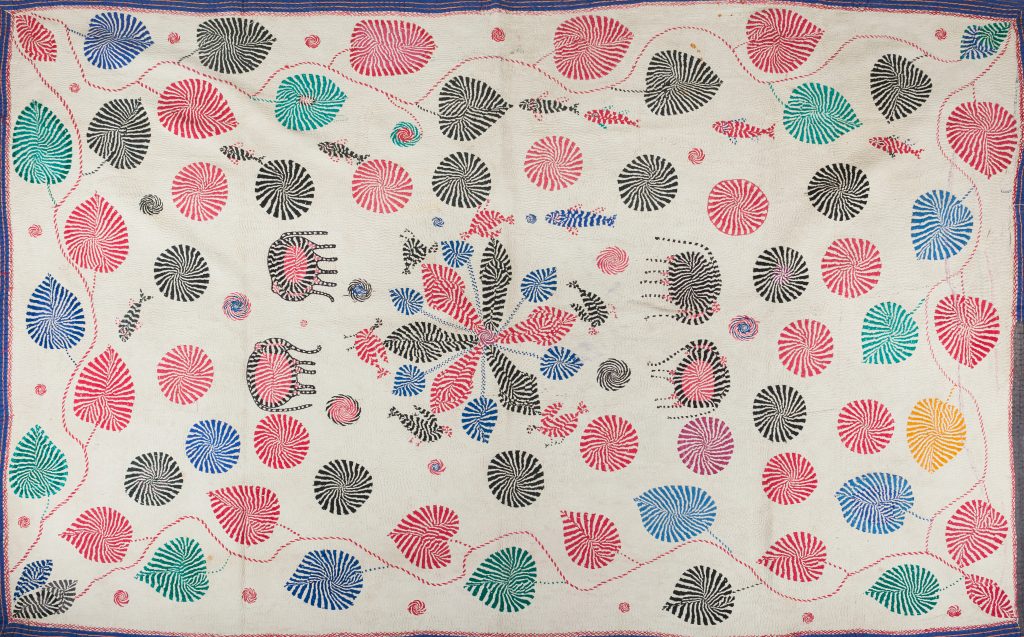

Kanthas were produced out of need and economic sustenance in which women reused their own scraps that were disused, and also to embroider, exercise and share skills. Sometimes, many hands made the same kantha: mothers passed them on to their daughters who would pick up the kantha and add it to its visual story and legacy. In these embroideries, we notice village life, animals, flora and fauna, but also geometric patterns, which allow us to speculate about the region the kantha was made in, and not just the everyday realities of the women who made them, but also about the stories they choose to tell.

Kantha with a leaf pattern made in Undivided Bengal, c. 20th century, Quilted and embroidered kantha

While working on this exhibition we encountered moments of humour like when one of us (Arnika) spotted one odd yellow leaf amidst green and red leaves in the kantha. We had instances where we would take each other through the textiles and really speculate – is this figure hiding behind a tree.. the hindu god Krishna? These moments made us feel closer to the makers as we chuckled over our laptops and zoom conversations. It made us feel a certain sense of closeness, as curators working together but also in relation to the women makers.

The makers didn’t just embroider the kantha but also used it as a quilt, a bed cover, to wrap their babies or as a handbag. These everyday activities with cloth would leave some marks, tears, loose threads and blemishes. We found some stains on the kanthas, and although in a museum, this might look like a case for conservation, for us, even the stains convey stories and experiences, perhaps of those people who kept the kanthas for so many years. They allow us to understand that these were everyday textiles that women were proud of; that while some parted with it, others retained it for special occasions. For our exhibition we chose to speculate, to read kanthas through different perspectives and to highlight kanthas as women’s work (even though some of them often carried embroidered inscriptions with the names of men).

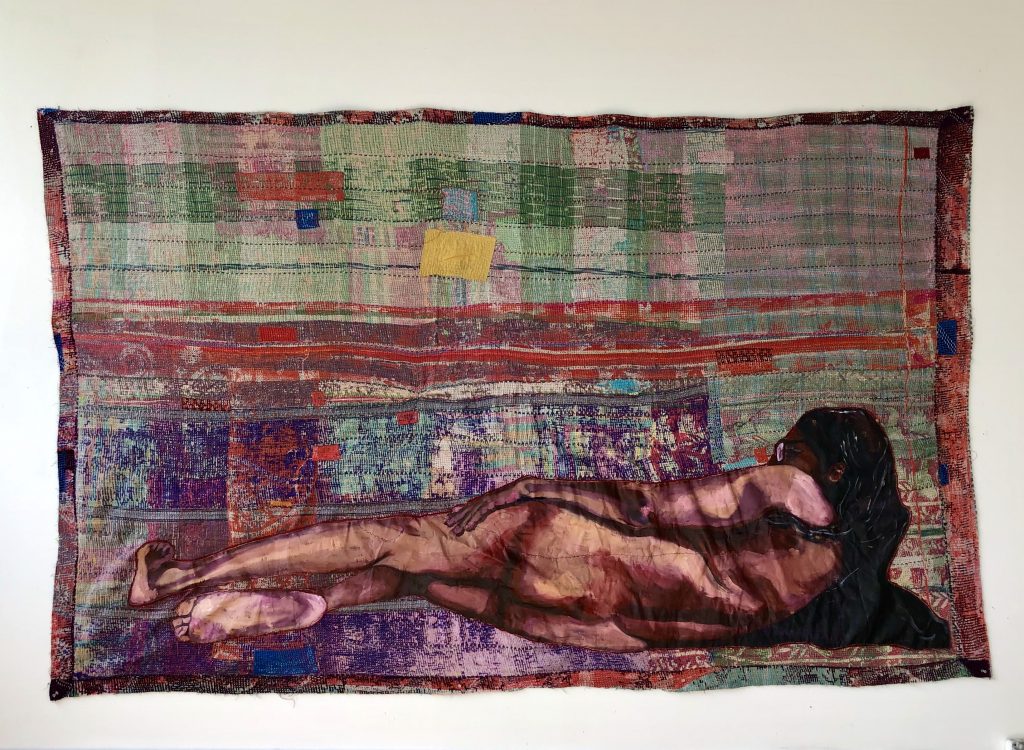

Speculation as a mode of curation allows us to trace patterns of relationality, between the work of contemporary artists and how textiles have influenced their work. We approach the materiality and immateriality of women’s labour and the interconnectedness of their roles in the domestic space as providers, caregivers and as beholders of generational relationships. Lastly, we speculate about the push and pull between invisibility and presence of women makers in institutional spaces.

Front Image of Kantha quilt titled करवट (The Turn), Bhasha Chakrabarti, 2020, Oil on used saree, used cloth and thread, Image Courtesy of the artist

We can relate kantha to quilting practices in other regions of the world but also to some parts of Karnataka where kowri and kawandi quilts are embroidered by women in their free time. This connection is also important in our choice of Bhasha Chakrabarti’s karvat quilt because her work is an archive of her mother’s clothing and her own identity, and her personal relationship to kanthas.

However, we can’t help but imagine what a physical exhibition would look like, especially experiences that cannot be replicated in the digital space. We would love for audiences to see the kanthas, experience their sizes and stitches, be inspired to make quilts of their own, to find mended and worn out parts, and imagine their histories themselves.

Arnika Ahldag and Vaishnavi Kambadur are part of the MAP team and have curated the Museum’s latest online exhibition – Painted Stitches, Woven Stories.