Blogs

Making of a Museum: The Ephemeral Nature of Exhibitions

Khushi Bansal

The fourth article in our ‘Making of a Museum’ series dives deep into the core role of the Exhibitions team in presenting interesting art historical narratives for audiences and the building of an institution.

Have you ever visited an art exhibition only to be engulfed by questions: Why this space? Why this artist? Why this artwork? The more I think about it, the more it interests me because each exhibition is so much more than what we see; at the end of the day, it is a union of different perceptions. Arnika Ahldag, Vaishnavi Kambadur, Riya Kumar, and Arshad Hakim partially form the exhibitions team at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP). They are helmed with the responsibility of conveying a story and perhaps even a history.

Arnika is our chief curator at MAP with a background in art history. Throughout her professional and educational career, she has approached her work from various perspectives, whether it be from the angle of art and labour, or performance and theatre. Vaishnavi is our assistant curator and comes from a textile background, wherein she has extensively studied fashion history and its production. Riya, our curatorial assistant, fascinatingly, came from a psychology background and drifted towards the arts during her time in college (having grown up around it helped too!). Arshad is our programme lead who started his art education through painting only to diversify and explore several other mediums and forms, including film, video photography, and text.

Although exhibitions are ephemeral moments, the process of creation is long drawn. In terms of the process, Arnika said, “There are countless opportunities for exhibitions to work with artists outside of the collection while at the same time keeping in mind the vision of MAP and the kind of exhibitions we want to show in the museum. As a team, we have to negotiate those. We must always keep in mind our local audience and then diversify outwards: we have to keep in mind our audience in Bengaluru, then Karnataka, then India and then globally. I think the curatorial idea forms over a long period; it is not always linear. We first focus on the curatorial idea and then look at all the artworks that help in supporting it. Often it is the other way around, allowing for many twists, turns and interesting encounters. Ideas that you did not consider suddenly unfold in front of you as you look at artworks and find these cross-connections.”

Ranjan Patel (Baroda, Gujarat) by Jyoti Bhatt, c. 1958, Silver gelatin print, PHY.00606

Having come from vastly different backgrounds, each team member brings something different to the table. Although they work towards similar goals and objectives, their curatorial practices at MAP are unique to themselves, and like everything else, it is a constant work in progress. Arshad said, “given that my background is in making art, I think the line between my artistic and curatorial practice is blurred. I definitely see one thing seeping into the other and that has its own challenges and joy.” Arnika added, “I always thought of museums as places of power in the art world. At MAP, we try to reach out to a broader audience and hope to build a connection. This way, we are not talking amongst ourselves but also reaching out to people who may be setting foot into a museum for the first time in their lives. How do they look at art? I see the work of the curatorial team as a bridge because we have the artwork, artist, and institution on one side, and then the audience on the other.”

The pandemic enabled the exhibitions team to explore multiple spaces in terms of both the physical and digital. This gives rise to a number of questions like, how do they curate these spaces? What is the difference? What are some of the things to keep in mind? To this, Arshad said, “they (the physical and digital) are two entirely different entities. There are benefits for both as well as fallbacks. It isn’t that one is better than the other; instead, it is about what your intention is and what aligns with that intention. Having said that, coming to an exhibit where people are physically present in a space is something which can never be replicated over a Zoom call.” He added, “with digital exhibitions, we can get audiences from around the globe as it is impossible for everyone to access something very physical.”

Snapshots of MAP’s recent digital exhibition on KG Subramanyan, Bahurupee in the Panorama, designed to mirror the mind map of the artist as well as curators.

This conversation took on a rather fascinating route at this point because it is very relevant to the team’s current ethos and practices. Arnika, at this point, went on to say, “I think the ‘curatorial’ always lies in the context. When you have a physical exhibition, there is an artwork next to another, in close proximity to others, and then there is you. This constellation does something. While curating a digital exhibition, on the other hand, you are projecting something on a screen that you then imagine on somebody’s phone, laptop or computer at home. This creates a different relationship between the art, the screen and the space. That being said, it is challenging to show a sculpture in a digital space because it is all about the relationship between the body, the sculpture, and the space in between. At the same time, we all have had a really interesting experience trying out different accessibility features in the digital and really using it as a testing ground to see what people need to access art and take this learning to the physical space. I think that is what I really appreciate about the last couple of years and the learning experiences with these digital experiences.” Vaishnavi chimed in here to say, “I agree with Arnika. We have thought about this so many times. Should the online space look the same as the physical space? How should the user experience be different? I would also say that we can show artworks we cannot share in physical space because they either do not exist anymore or can no longer be transported.”

Speaking of institutions and putting out a story to a broader audience, the role of the exhibitions team is to enable people to create their own perceptions rather than forcing an idea on them. To this, Arnika (with the others chiming in agreement) said, “I think a lot of our curation is about asking questions and not knowing the answer. We try to work around the idea of engagements while bringing different possibilities to the table. We have been conscious to not hit people with art historical knowledge on the head as we try to not sound preachy and the bearer of all information. Rather we try to create a space for doubt, wonder, creation and curiosity. Instead of providing people with a statement, we ask a question. What is the space for speculation? What is the space for dreaming? Everything has multiple facets, and we try to keep it elastic.” Riya continued to add, “We also question scholarship. Question why said historian is saying something about an artwork and whether their context makes sense or not.”

When one considers a space, setting and climate immediately come to mind. What is happening around you, for instance? Curating exhibitions is accompanied by a lot of self-awareness so that biases are not explicitly highlighted. At the end of the day, we want people to create their own perceptions. To this, Arshad said, “in some shape, way or form, we are constantly responding to something, whether it is at an individual capacity or institutional capacity. In terms of the work that we do at MAP, our work is driven by themes and context, along the lines of conversations and provocations. This is a guiding principle for us. If we are doing something, what comes out of it? It is not just about the act of doing but also creating and questioning a rhetoric.” Riya chimed in with an example here, “on one Museums Without Borders episode, a photograph we looked at had an ethnographic, caste angle to it. This was interesting to navigate as an institution because these were the concerns we wanted to unpack, but it is also important to keep in mind the context and the time period the artists were working in.”

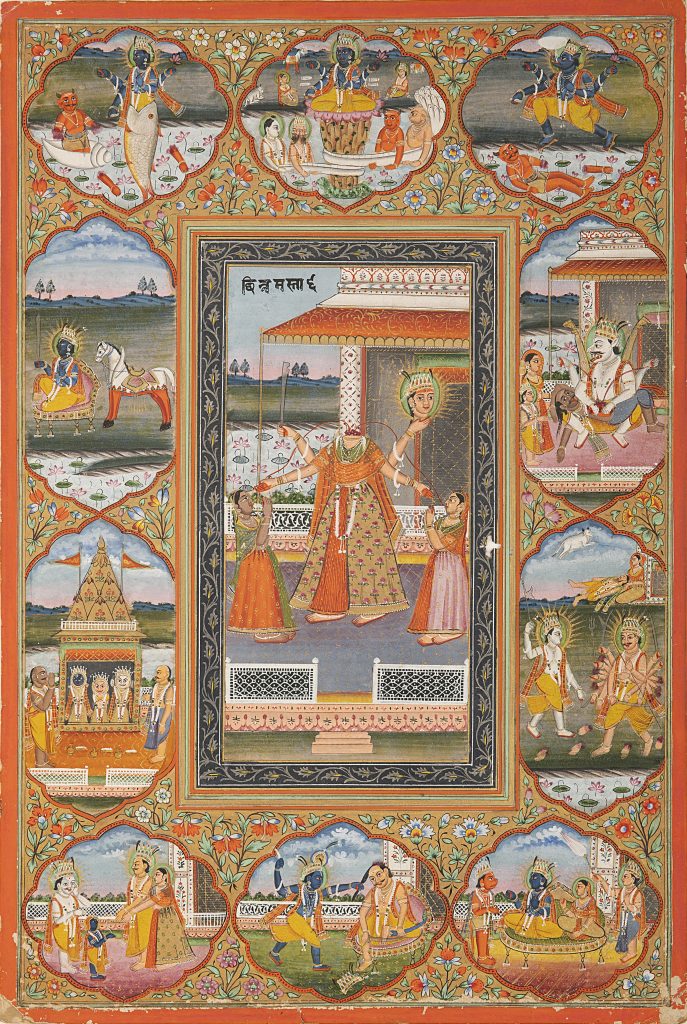

Chinnamasta and Avatars of Vishnu by an Unknown Maker, Undated, Opaque watercolour on paper, PTG.01732

A favourite question in this interview series has been, “what is your favourite artwork in our collection?” This gave rise to some exciting points of conversation as the whole interview started winding down. Riya began by saying, “I have realised that it is the story behind the artwork as opposed to aesthetics. There is this painting of Chinnamasta, which I talk about a lot. It is fascinating because, typically, Chinnamasta is depicted naked, standing in a cremation ground; she is associated with death and destruction. But in this painting, she looks like a princess; she is fully clothed and adorned in jewellery. So for me, it’s super interesting the way a patron or even the artist changed the iconography of the goddess and made her something completely different. The idea of patronage and artistic interpretation is fascinating.”

Manjit and Fil Talking by Arpita Singh, 1990, Acrylic on canvas, MAC.00506

Arnika continued, “I think MAP has made me fall in love with Arpita Singh again. I have always liked her work, but it was always on the periphery. I think I have the privilege of repeatedly looking at her work in person. The work in Kamini’s (MAP’s Director) office is really something that made me look at the artist again and look at the kind of space she creates. I can look at it my entire life and never get bored.”

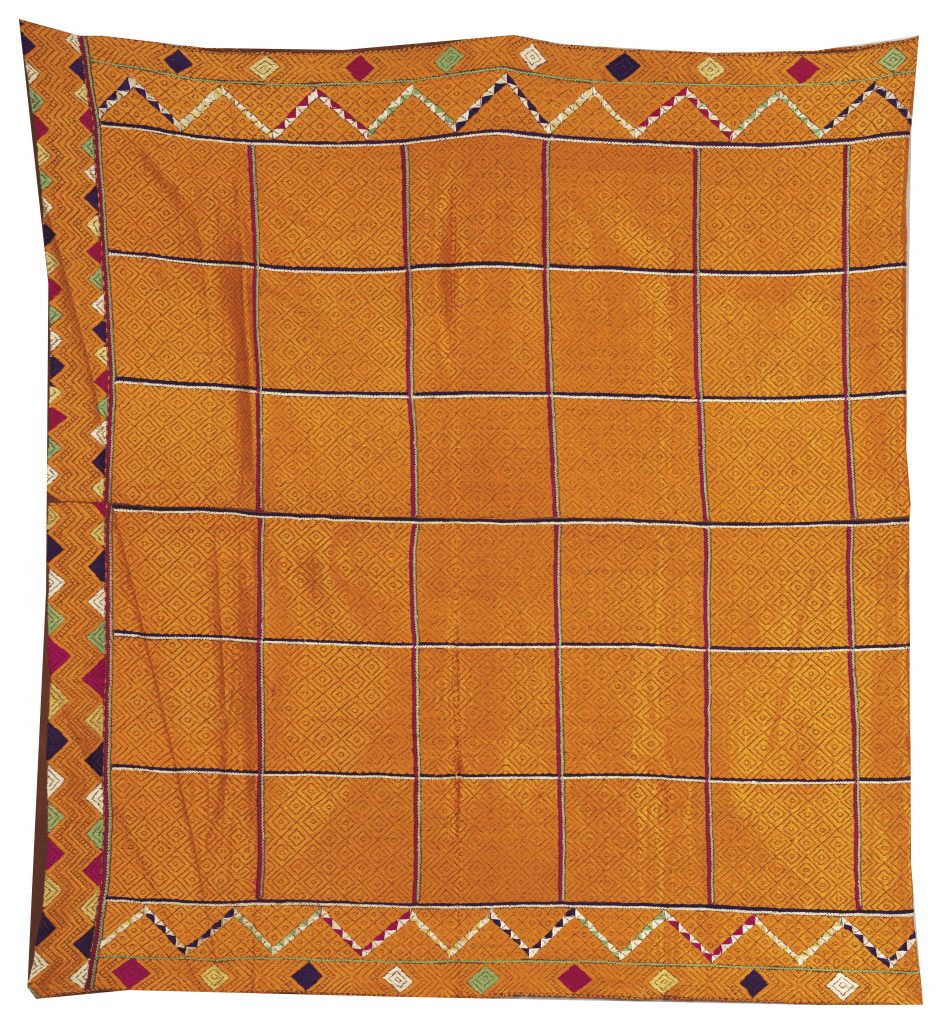

Arshad continued, “A Phulkari shawl. All credit here goes to Vaishnavi because I appreciate how she gets into these minute details that I would have never imagined. She has opened my mind up to the world of textiles. The thing with textiles is that they are loaded with socio-cultural histories that are often so subtle that we do not notice them.”

Vari Da Bagh Phulkari by an Unknown Maker, c. 1930, Cotton, floss silk, TXT.00166

Kalamkari Palampore by an Unknown Maker, mid 18th century-mid 19th century, Cotton, cotton, natural dyes, TXT.00067

Finally, Vaishnavi said, “For me, it would obviously be a textile – a Chintz wall hanging. The textile has these birds that have been painted by mixing different species. There are at least five varieties of pheasants: one has a twisted beak, and the other has different kinds of wings. However, it all merges into one singular bird. This specific hanging has so many motifs, all based on reality but heightened. It is absolutely magnificent.”

A recent graduate from Central Saint Martins, London, Khushi Bansal is an aspiring curator with a keen interest in baking a perfect loaf of bread. She is an Archivist in MAP’s Collection team.