Blogs

How the Plague Outbreak Led to a New Township in Bengaluru

Basav Biradar

Exploring the origin story of Fraser Town, an area that came to be as a result of the Mysore administration’s response to the devastating plague epidemic in the early 20th century.

Innocuously located on the roadside, dangerously close to a BESCOM control box, at the intersection of Coles Road and Mosque Road, is the stone plaque commemorating the foundation of Fraser Town. This plaque declares that the new neighbourhood was named after the then Resident (aka British representative) of Mysore – Stuart M Fraser – and was so christened by the then collector, F J Richards. Although most of the current residents of our bustling metropolis might not even notice this plaque dated August 1910, it is a dedication to how the Mysore administration responded to the devastating plague epidemic in the early 20th century.

Fraser Town Foundation Plaque, Located on the corner of Coles Road and Mosque Road, Bengaluru, Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

The plague first appeared in Bangalore city in 1898 and continued to cause misery for more than a decade. The disease thrived in the congested and poor localities of the town, but the spacious upper-class neighbourhoods and the English parts of the town were largely unaffected.

There are a lot of similarities between the plague epidemic and the current Covid-19 pandemic; not least of them being the fact that the same law – The Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897 – has been invoked to implement control measures. Even then, isolation of infected people and disinfection of their possessions and dwellings were considered preventive measures. Also, similar to the lack of sufficient information and research around Covid-19, there was very little know-how of the plague back then.

But unlike today, in the early 1900s the locals did not take too kindly to the draconian methods of forcible eviction from their houses (to be moved to isolation centers outside the city limits), or the forced disinfection of their dwellings, and sometimes, demolition of their humble dwellings. There were even rumours floating around that the British were using plague as an excuse to kill all native Indians. Hence, many people kept the disease a secret and buried their dead secretly at night in the cemeteries. In some cases, fuelled by the conspiratorial rumours, people left dead bodies in the compounds of the British official residences.

Sir Stuart Mitford Fraser by Walter Stoneman, Bromide print, 1920, NPG x67087, Image Credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

In addition to managing the rapidly spreading disease, the authorities had to deal with several other issues: most of the sanitation workers and sweepers left the city overnight – due to the fear of plague regulations – leading to a precarious situation with garbage piling up all around the city. There was also considerable hesitancy among people about the medication and inoculation recommended by doctors. In his book on Plague-proof town planning, the British Municipal Engineer J.H. Stephens wrote: “Bangalore looked like it will soon expire, under the weight of its own unburied filth and fermenting rubbish”.

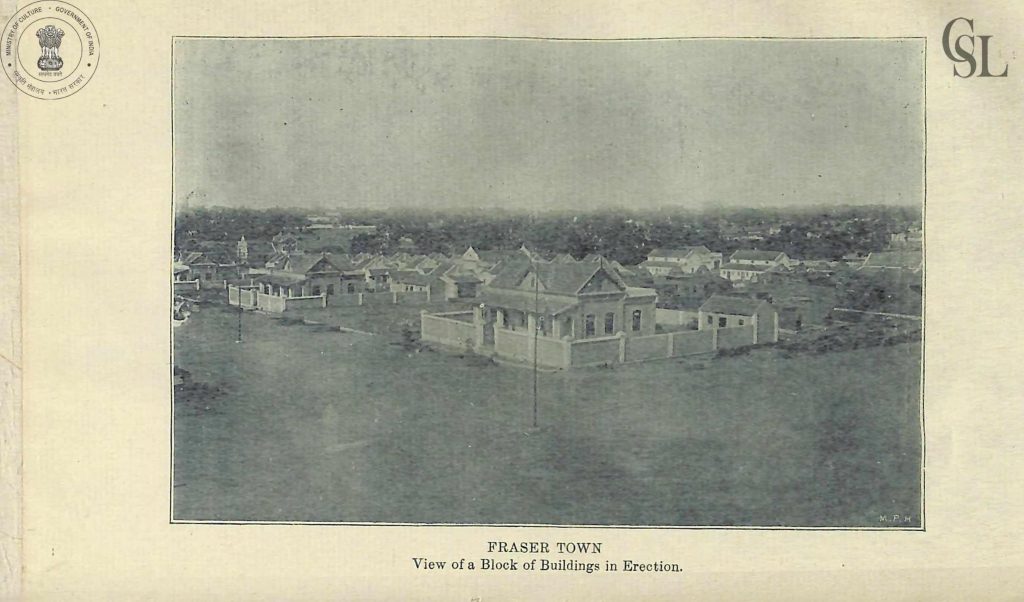

View of a block of buildings in erection in Fraser Town, from the book ‘Plague Proof Town Planning in Bangalore, South India’ by J.H. Stephens (Methodist Publishing House, 1914)

Amidst all this, the newly formed plague committee continued their investigation into the main causes of the disease by examining how it infected houses, and concluded that while rats and rat fleas were carriers of the plague, the probable cause was water stagnation and lack of ventilation in congested areas. As a result of this understanding, a decision was made to construct a new “plague-proof” residential area and rehabilitate the people living in the congested areas in these new residences.

Builders and contractors such as Rao Bahadur Anna Swamy Mudaliar, Khan Bahadur Hajee Ismail Sait, and Rao Bahadur Maigandadeva Mudaliar were entrusted with constructing houses in this new locality. The measures undertaken for “plague-proofing” included countersinking of roads to enable quick water draining, high basements of houses built in stone, floors built in stone slabs or tiles and use of Mangalore tiles for roofs.

Thus, a new plague-proof township named “Fraser Town”, with as many as 400 houses, was built to rehabilitate people displaced from congested neighbourhoods in the city.

Basav Biradar is an independent researcher, writer and filmmaker based in Bengaluru. He is the founder of ‘Historywallahs’ – a heritage consulting organisation. He teaches courses on Indian cinema and theatre at Azim Premji University as a visiting faculty.