Blogs

Home, a Distant Place

Radhika Iyengar

Zoya Siddiqui’s ongoing digital exhibition at MAP reaffirms the complexity of migration and displacement in art.

Against the backdrop of pale yellow wallpaper with tendril-like motifs, a solitary dark-brown sofa fills the space. Its sprawl magnified. A wall-hanging featuring a dome and a minaret flanked by twin turquoise-tasselled decorations, and a calendar, are the items decorating the wall. Though the photograph depicts a lived-in home, there is a sense of stillness and emptiness.

This photograph belongs to Lahore-based artist, Zoya Siddiqui’s Geology of a Home, which features a collection of a hundred similar images where the couch plays the central character. The project took root at Lancashire’s Brierfield Mill, UK, a shuttered textile mill that was once a source of livelihood for countless Pakistani immigrants who worked there in the 1970s. The homes surrounding the mill were built to provide residential support to the workers. In these homes, a sofa formed the fulcrum of the living rooms, where the families gathered to unwind. In the 1990s, the mill closed down, rendering several workers jobless. While the mill becomes a marker of capitalism, the sofa can be interpreted as a symbol of an emigrant community’s collective struggles and shared past.

Geology of a Home, 2015, Zoya Siddiqui, Live video installation and 100 photographs, Image Courtesy: the artist

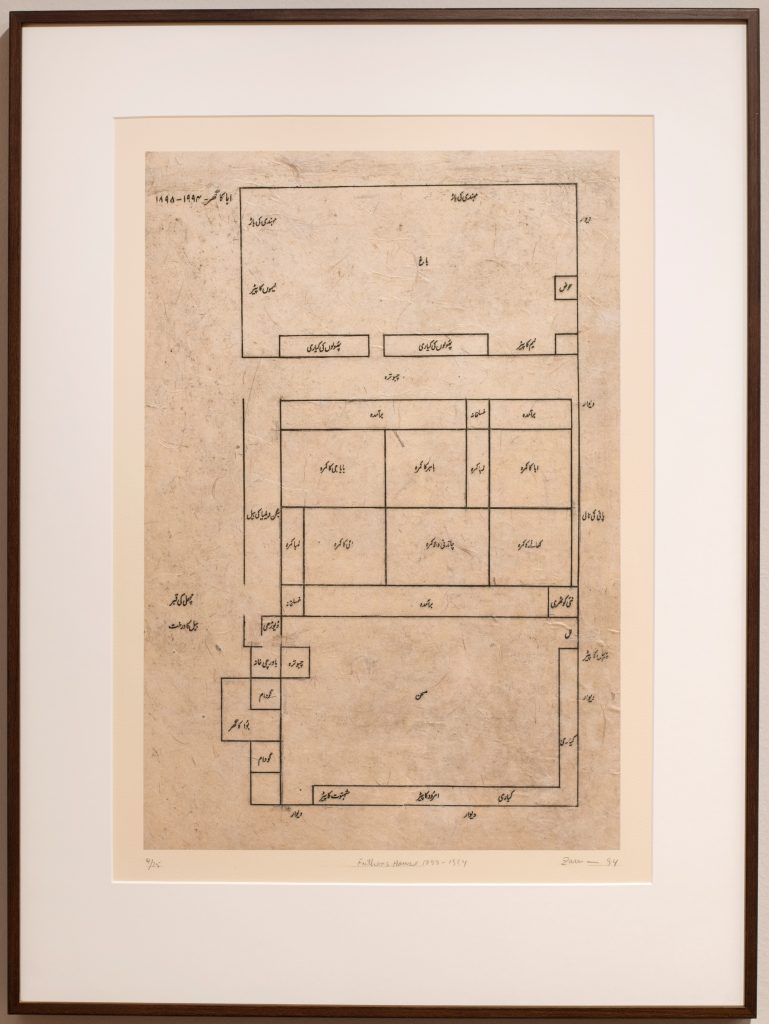

Themes of migration and displacement are a strong, recurring presence in many South Asian artists’ works. These artists explore the plurality of ‘home’ and the very real possibility of its impermanence. The oeuvre of cerebral artist, Zarina Hashmi, serves as the epitome of such works. Cartographic boundaries, dislocation and transition, loss, and a profound longing for home, feature in her minimalist works. Father’s House 1898-1994, for instance, is a blueprint of her birth home, made in response to her father’s demise in 1994. Home I made A Life in Nine Lives (1997) is a group of nine floorplan etchings, each recording the dimensions of the homes Zarina has inhabited, including those in New York, Paris and Bonn. These prints on paper are a visual memoir, where paper (a predominant medium in Zarina’s practice) underscores the fragility of life.

Father’s House 1898-1994, 1994, Zarina, Etching on paper, Collection and Image Courtesy: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Home I made, A Life in Nine Lines, Zarina, Etching on paper, Image Courtesy: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Reena Kallat’s body of work also investigates multiple narratives of migration. In Woven Chronicles (2011-2016), across a panoramic wall, she maps the trajectory of labour migrants on a global scale. Using multihued cables, Kallat traces the movements of those who’ve crossed borders and settled in adopted lands. Not only do the wires symbolise web-like migratory footprints, but also the transference of information (culture, knowledge, language, genetics). In Leaking Lines (2019), she investigates the nature of man-marked borders. It gestures to the demarcations drawn across territories – like the Radcliffe Line (Partition of India) or Green Line (1949 Armistice Line) – that have colossal implications on the lives on either side.

Woven Chronicles, 2011/2016, Reena Kallat, Circuit boards, speakers, electric wires and fittings; single channel audio (10 min.), Installation view: Museum of Modern Art, New York; Photo Credits: Reena Kallat Studio

Leaking Lines, 2019, Reena Kallat, Charcoal, gouache, graphite, nails and electric wires on laser cut and embossed Arches paper, Installation view: Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai; Photo credits: Iris Dreams

But decades before Kallat, veteran artist Krishen Khanna poignantly chronicled the enormity of displacement, borders that birthed familial fissures and the insurmountable grief of being uprooted, through his art. Born from his own experiences of seeing the chaos of Partition, Exodus 1947, for instance, gives glimpses of the painful exodus that left an indelible wound in the country’s collective memory.

The preoccupation with notions of belonging, of alien lands, of the self, and the overwhelming possibility of being or becoming the ‘other’, pulsate through these works of art. The artists make us question the comforts of home – a symbol of stability – and make us painfully aware that a ‘home’ should not be taken for granted.

Radhika Iyengar is a journalist who writes on issues that meet at the intersection of culture, gender, human rights and politics. She holds a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University, New York. Her work has been published in Al Jazeera, Huffington Post, Vogue, Open magazine and Mint Lounge. She is currently based in New Delhi.