Blogs

Face Value: An Introduction to Portraiture in Indian Art

Shubhasree Purkayastha

As humans, our desire to record ourselves is perhaps as old as the history of art making itself. The story of portraiture in Indian art is a fascinating journey, encompassing notions of the real and the ideal, the observed and the imagined.

“Have you my portrait so that you will have my presence all the days and nights that I am away from you.”

– Frida Kahlo

As humans, our desire to record ourselves is perhaps as old as the history of art making itself. From palm prints in early caves to painstakingly gouged out ‘x was here’ messages on school desks, we seem to have a primal need to record our presence – whether with a view to leaving a legacy, building a sense of belonging, or simply communicating an idea, a sense of ourselves and our lives.

The art of portraiture therefore, is perhaps unsurprisingly one that was patronised and practiced across societies, recording histories both cultural and personal. The story of portraiture in Indian art is a fascinating journey, encompassing notions of the real and the ideal, the observed and the imagined.

The Ideal & The Real

The focus of portraiture in the subcontinent, in ancient times, was primarily that of the idealised form – the idea of spiritual and moral perfection achieved through stylised physical features, that were carefully laid down in canons. Artists followed these rules to the T, from the way in which different types of figures (male and female) were meant to be represented to the iconographies for deities or deified historical figures. The rules were rather elaborate too, from the ways in which the eyes should be drawn suggesting different emotions, to the postures that were acceptable for a certain kind of character.

Jumping ahead to the Mughal period, different schools of miniature painting across the subcontinent began to develop their own distinct styles of portraiture. Gradually, with exposure to realistic depictions in the form of paintings from Europe that were presented to kings by traders as gifts, and its subsequent influence, the stylised portrait began to slowly recede in importance.

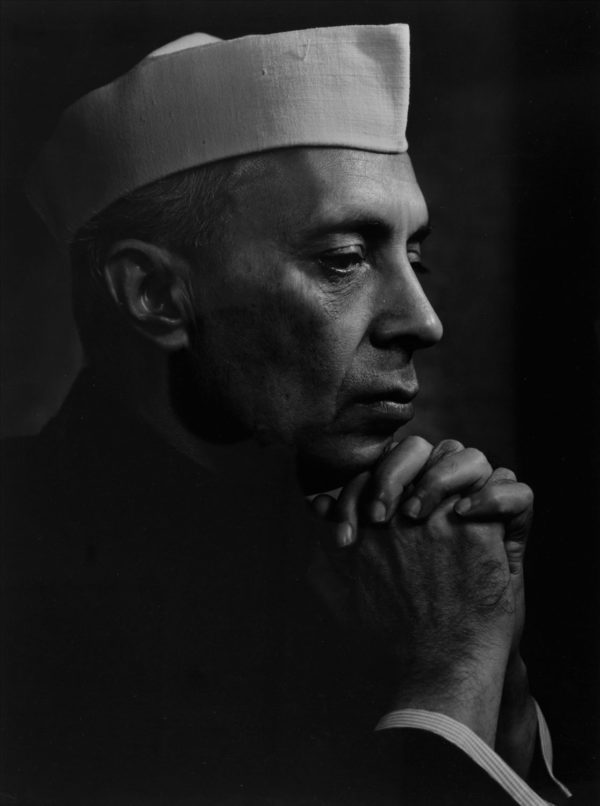

The principal shift in portraiture though, was marked by the advent of photography and coincided with British rule in the 18th and 19th centuries. The accuracy of the camera began to slowly replace painted portraits, and the British began to utilise the camera to document the ‘natives’ as part of their extensive colonial anthropological project. These photographs were real, insofar as they recorded real sitters. However, the manner in which they were staged and then used to build a narrative of the colonised subject, underlines the way in which photography was employed to create a language of representation. A coded interpretation not entirely dissimilar, perhaps, to stylised portraiture, though its objective was entirely different.

Portraiture & Patronage

In India, as elsewhere, the ability to commission portraits in earlier times was limited to the privileged few – primarily royalty and nobility. The relationship and power dynamics here, between patron and artist often coloured the final work. For although a portrait conventionally refers to the likeness of an individual, the representative goals and values of a portrait were often far greater. Throughout history, portraits have been used to exhibit the power, virtues, tastes, wealth and other qualities of the sitter.

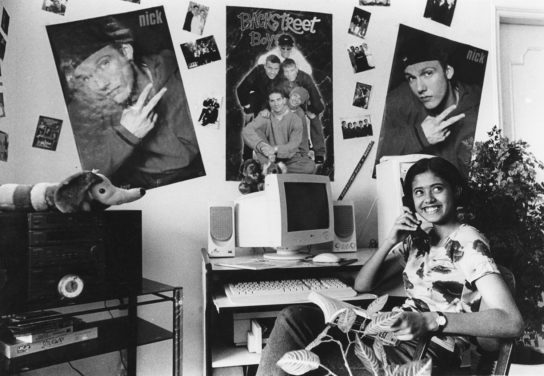

Even with the setting up of photographic studios in the 19th century, portraiture continued to be an opportunity largely available only to the richer sections of society. In the 20th century, with the invention of handheld cameras and cheaper processes, photography finally moved from the studio into our homes and streets, bringing about photojournalistic, family and candid portraiture.

Portraiture & Invention

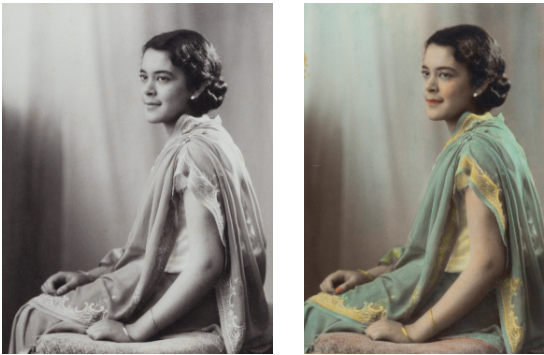

You’ve probably heard the phrase ‘necessity is the mother of invention’. This seems to have been the case with portrait painters in the 19th century who were afraid of losing their livelihoods, given a growing fascination with the camera and its incredibly accurate documentation. They began to offer a new service to their clientele, which led to a new genre described as painted photographs. Globally, the term is usually used to describe a photograph that has been mildly tinted. In the Indian context however, a whole range may be seen: from a mild application of colour to photographs that were almost entirely covered with paint. Apart from adding colour, in some of these the painters also added details in the garments, jewellery or backgrounds that weren’t part of the original image. There are also instances of the same photograph, painted in different ways.

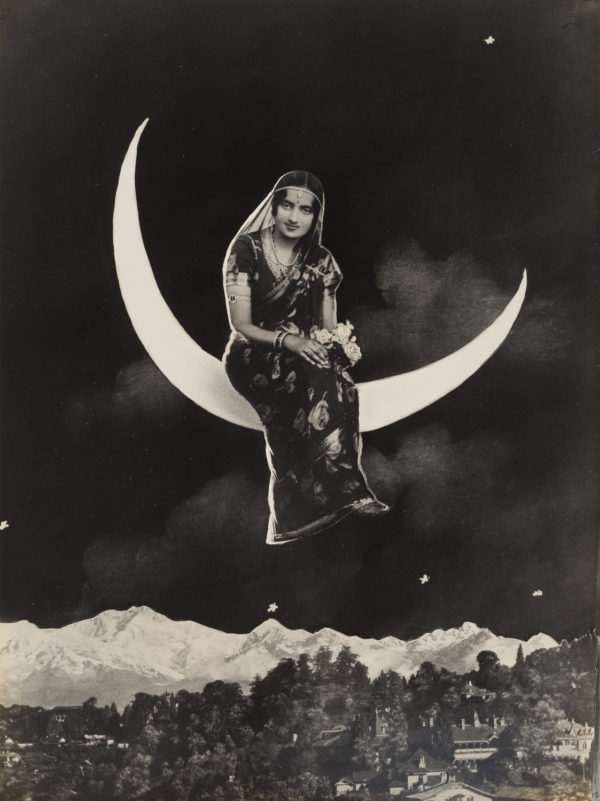

With Photoshop being part of everyday vocabulary now, we are aware of how easily images can be altered today. However, image editing techniques have long formed part of art traditions, even darkroom photography. Portraits with their need to communicate something about the sitter beyond mere likeness were often staged products. Subtly sometimes, through their use of backgrounds, props, symbolic objects, and technical strategies. Sometimes though, they were manipulated in more obvious and imaginative ways.

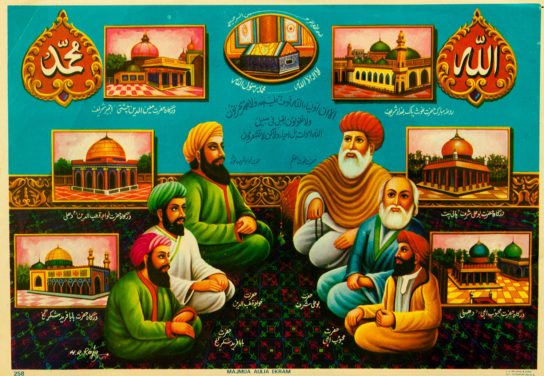

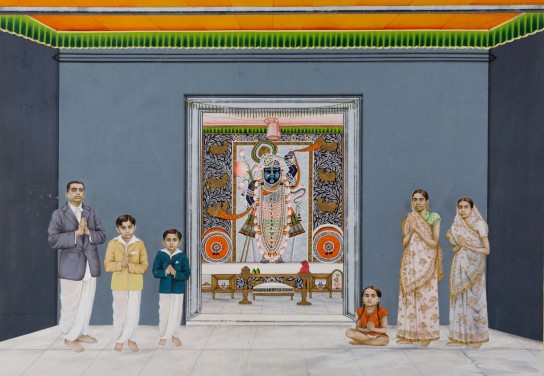

One could write a whole book on the nature of imagination in portraiture. From the Mughal emperors who used it to further imperial and other narratives (the psychological portraits of Jahangir are incredible examples here), to local traditions of creating group portraits of saintly figures from different centuries and geographies together and the Manorath paintings of Nathdwara that served as souvenirs of pilgrimage, allowing devotees to see themselves represented virtually in the act of viewing the deity.

Portraiture & Identity

A key genre that cannot be overlooked in any overview of portraiture is that of the self-portrait. The rich history of self-portraiture that we have evidence of, shows us that artists were grappling with various ideas of identity, ownership and self-expression from the earliest of times. With the development of the individual Artist (with a capital A) in modern times, self-portraits were to become an even more significant part of artistic practice and visual culture. Modern and contemporary visual artists, across the world and in India, would also push the envelope on what constituted a portrait by presenting abstract, semi-abstract and surreal depictions.

Today, artists continue to experiment with portraits across mediums and subjects, celebrating the beauty and diversity of the human form through this genre. With advancements in technology and emergence of the selfie trend, portraiture today has become the most democratic artistic medium. Somewhere along this journey from exclusively commissioned paintings to phone selfies, portraiture also became a means to self-awareness and reclaiming agency. No longer passive subjects, we have become active role-players in the creation of our visual identities – we know who we are, and more importantly, we know exactly how we wish to be seen.