Blogs

Curtain Call: The long running Theatre of Life in Goa’s long standing homes

Ulka Chauhan & Samira Sheth

[Musings from the book, The Memory Keepers & Future Seekers: Portraits of Heritage Homes in Goa by Ulka Chauhan]

There is no stage with productions as theatrical as life itself. Live performances unfold within each of our homes. “The house is a stage for early seductions, for homework being written, for swaddled babies that freshly arrive from the hospital, midsummer dusks and the warmth of freshly baked bread,” says Swiss born British author and philosopher on everyday life, Alain De Botton, in his book, The Architecture of Happiness. But how moving would this home-stage be if its show ran through centuries with multiple generations of ancestors and descendants as its players?

Goa’s long standing heritage homes perfectly embody this long running theatre of life. These ancestral homes have been headliners for centuries, with some lived in by the same family for over 300 years. They are the stage on which family stories play out and memories are made and kept — carefully passed down through time — and well preserved within their patinated walls.

Across Goa’s paddy and palm fringed heartland, façades of red oxide, yellow ochre and indigo blue peer out of tropical front gardens lush with old mango, tamarind, jackfruit and coconut trees. A quick glance at the exterior of these homes is enough to recognise their distinct architectural language. As Goan artist, Dr. Subodh Kerkar rightly says, “If one takes a drive from Surat to Kanyakumari along the west coast of India, the landscape is almost the same. There is the seashore, swinging palm trees, rice fields, rivers and hills. However, the moment one enters Goa, even before you can speak to anybody, the houses of Goa start speaking to you.” Steps lead up to the front door of the home with in situ chairs on either side where the homeowners sit and shoot the breeze with passers by, a long balcão (verandah) often stretches on either side of the front door adorned with a series of decorative columns, ornately carved wrought iron railing and patterned wooden window frames with oyster shells speak of a time when glass was not available in Goa. Low slung terracotta tiled sloping roofs shield the home from the harsh summer sun and fierce monsoon rains.

Situated at the end of an Ashoka tree lined street, in the picturesque village of Curtorim in South Goa is one such quintessential home, that of family Viegas. Standing at the balcão looking in, one sees through a corridor leading from the entrada with its pink textured walls and geometric mosaic flooring to the very heart of the home, the kitchen. Within this liminal space is the fragile frame of the elderly Maryanne Catherine D’Souza e Viegas as she sits at her bible table practising her morning ritual of colouring, an activity that was prescribed by her daughter to stimulate her mind and boost her memory. The hushed, meditative corner is periodically orchestrated by gentle bursts of laughter and footsteps of the grandchildren Aditi and Mira as they run across the room to the Sala during their weekly Sunday visits. Once the grand ballroom of the home, the Sala is now Joaquim Mariano da Piedade Rafael Viegas’ favourite room which houses his archive of rare English and Portuguese books, magazines and newspaper clippings. With a razor sharp memory, it is here that the now 92 year old Rafael welcomes visitors with lively banter regarding the idyllic slow and simple Goa of his time, compared to the unfortunate fast and ‘smart city’ it is becoming.

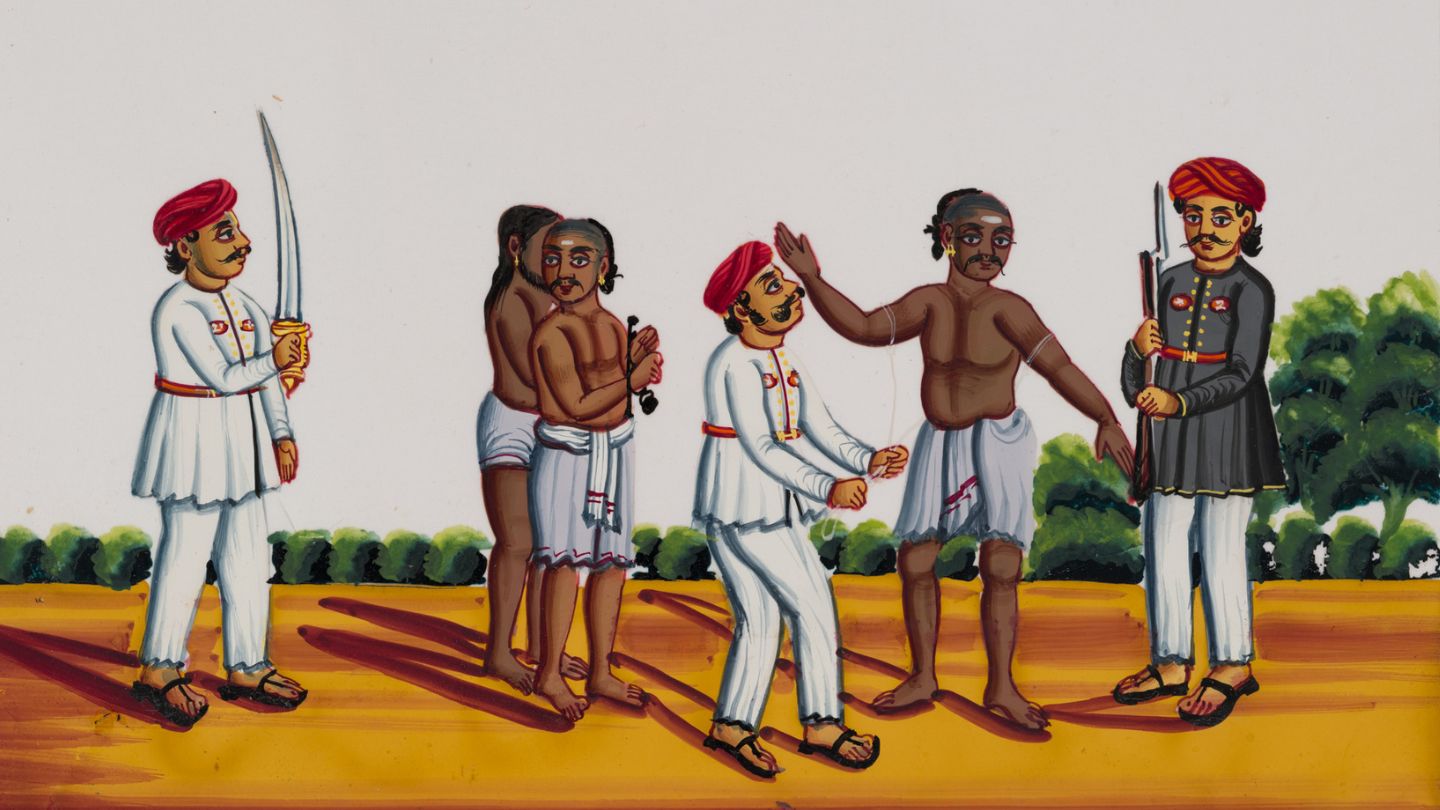

The Viegas home was one of many such Goan homes that were built during the colonial Portuguese era, a 450 year old rule that spanned from 1510 -1961. During this period, Marquis de Pombal, a minister in office in Portugal, introduced a series of reforms for an administration and society in Goa in 1769. He proclaimed on behalf of the King that the differences between the rulers and the vassals would not be based on colour but on merit. This reform along with the adoption of Neo-Christianity gave rise to a new Goan elite and in turn to a new architectural language.

But how can one begin to grasp such a vast stretch of time? How can we catch glimpses of such a distant past in the present day?

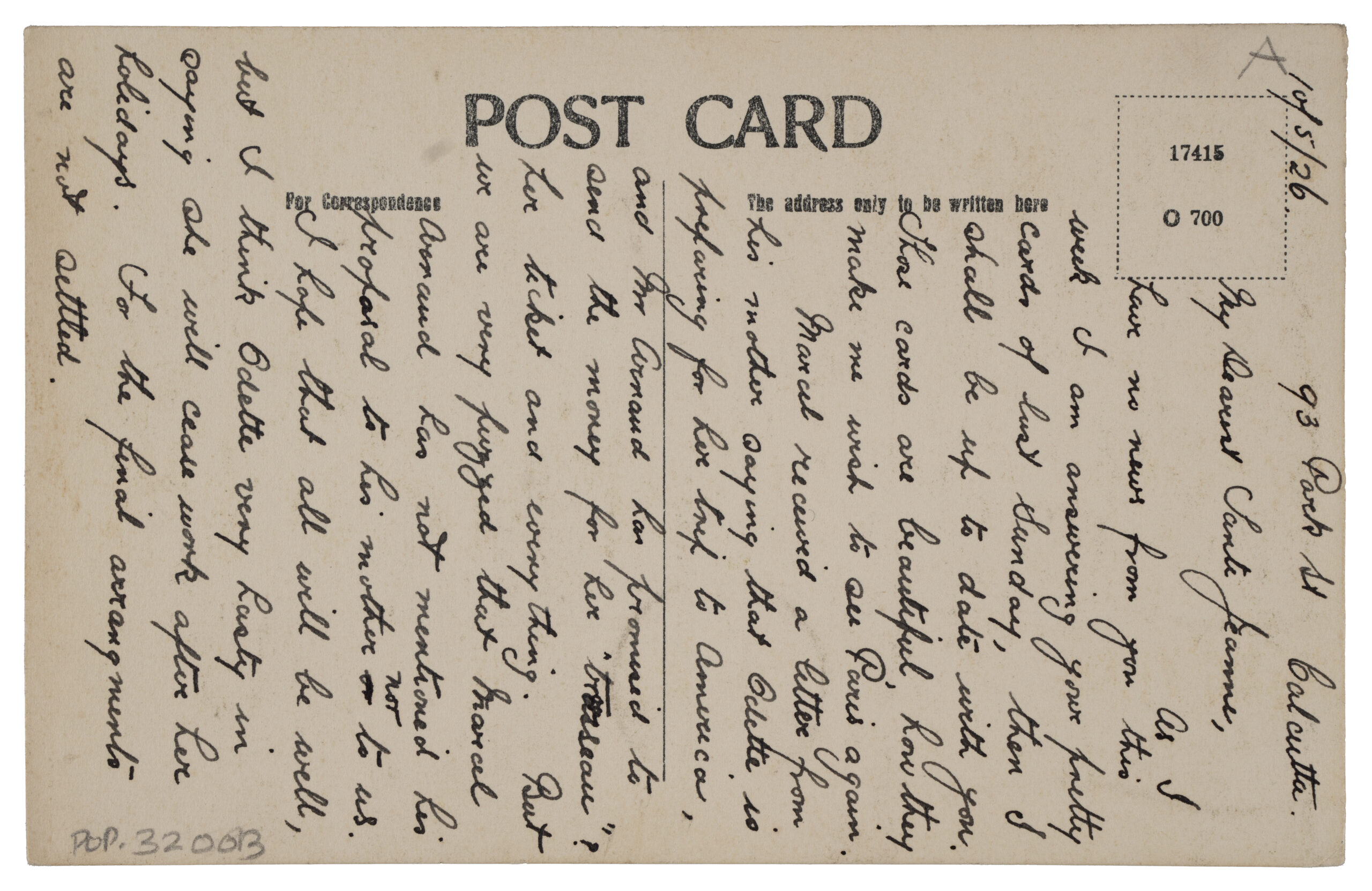

Visiting Goan homes of the era, stories of the hazy past come softly into focus. Hints of the transoceanic trade and multilayered histories of Goa; seismic shifts in food, faith, music, language, clothing, and even country as the location of these homes changed from Estado Português (Portuguese State) to India upon Liberation in 1961. Each of these Goan homes with their occupants and objects are keepers of memory, of a multitude of stories that tell of a time when Goa was the capital of the Portuguese Empire in the East; the longest lived colonial empire in European history lasting almost six centuries with colonies that stretched across the globe having bases in Africa, North America, South America, Asia, and Oceania.

Not far from the Viegas home, is the mansion of the Figueiredo family in Loutolim where gilded mirrors reflect rooms filled with evidence of Goa’s culturally coalesced past. Pedro Figueiredo de Albuquerque de Oliveira Novais, the only male scion to run the home in the last 60 years, previously managed by the strong women of the Figueiredo family, offers deep insights into the sophisticated splendour of his home and of Goa. Opulent Belgian crystal chandeliers, intricately carved antique furniture in dark maple, rosewood and Burma teak, rich textiles including a Zardozi saree with gold filigree work worn by his grandmother, the late Maria de Lourdes Figueiredo de Albuquerque (1929-2021) during her time as a Member of Parliament in Portugal; family photographs including that of his mother Maria de Fatima Figueiredo de Albuquerque as she performed the Dekhni (one of the oldest dance forms of Goa combining Indian melody with Western rhythm) in Paris; long tables laden with custom made fine porcelain from Macau, Japan and China in the distinctive family colours of orange and gold; an entire set of silverware gifted by King João V of Portugal in 1740; and ornamental objets d’art with touches of ebony, ivory, mother of pearl, jade, turtle shell and lapis lazuli abound in every corner of the sprawling Figueiredo Mansion.

On one of many visits to the Figueiredo home, Pedro’s mother, Maria de Fatima Figueiredo de Albuquerque, cooks a delectable meal of Cataplana, a Portuguese equivalent of the more popularly known Spanish Paella. Over a long and languid lunch in the grand Sala with numbered dining tables which can be connected together to comfortably seat up to a hundred guests, Fatima reminisces on the elaborate parties her grandfather used to host. “As a child, I had never been to the big dinner parties. We were allowed to come wish the guests but not to sit at the table. Boys could sit at the big table after they turned 15 and girls after 13 years of age. Once there was a guest who could not make it and my grandmother called me to sit at the table. It was an amazing experience for me. I was almost 12.”

But what is it that makes these homes special? Beyond the glittering chandeliers, precious antiquities and sprawling salas, it is the residents’ attachment to their home that speak volumes. In current times of mobility, of frequent locating and relocating, where the born and bred attachment with a place is almost a thing of the past, it is these Goan families’ connectedness to the home and their land that is truly remarkable.

Fatima lived in Mozambique, Brazil and Portugal, travelling all over the world especially with her job as Creative Director at Estée Lauder, Portugal. However, the call of Goa where her mother eventually lived, was too compelling, and the multilingual (she speaks Konkani, English, Portuguese, Spanish, French and Italian), cosmopolitan, independent current matriarch of the family returned to live in the home of her childhood and fulfil her brother’s wishes – promising to look after her mother and her heritage home. And so, just a few years ago, both mother and son, Fatima and Pedro, changed trajectory, returning to Goa, coming back to the centre that holds it all together – their house, the Figueiredo mansion.

“I did not come here to be seen as a bhatkar or a big landowner or heir. I came here to maintain the history that the house has, because that is my main purpose,” says her son Pedro of their move to Goa. But with changing times, will these homes remain in the same family for much longer? Or will their final curtain soon be lowered?

Álvaro Savio Rafael Viegas, son of Rafael and Maryanne Viegas, architect turned future tech entrepreneur who divides his time between Berlin and Goa, says reflecting on the future relevance of Goan homes, “Goan houses are always a dialogue, nothing is permanent, everything is in transition, and change is inevitable.” This “dialogue” is perfectly evident in his home in Curtorim. His bedroom, a sparse and contemporary living quarter was refashioned from the old storeroom where firewood to warm water used to be kept. His hi-tech office, remodelled from what was once the family kitchen.

“Now these spaces stir creativity,” says Álvaro. While he has an appreciation of the heritage home he grew up in, he says, “It’s nice to have an old house with more modern amenities, a fusion of the old and new.” And so, a vinyl record player takes pride of place in his smart office where the light filters in through oyster shell windows, a rogddo (the semi-circular grinding stone used in Goan kitchens) and other old kitchen appliances are used as landscape elements around his backyard and the exposed mud walls, rammed layers of earth are framed as design elements. Álvaro plans to enhance the creative possibilities of the old home further as an “homage to my father, as a bridge between my world and his.”

As the staging on which life plays out within these Goan homes changes over time, so too do the players and the acts themselves. The script shifting in pitch and tone between the past and present, and making an interesting exchange about an uncertain future.

With the current sea-change in Goa caused by the proliferation of development – second homes, hospitality and gastronomy – which is threatening the very identity of Goa, there is one thing that remains clear. It is the long running theatre of life in Goa’s longstanding homes that stand as mute, or rather as eloquent witnesses to the story of time.

[Ulka Chauhan and Samira Sheth have co-authored this essay. All photographs in this essay are courtesy Ulka Chauhan, used here with her permission.]