Blogs

Common People/Uncommon Portraits

Prof. BN Goswamy

“On occasions of this kind (formal meetings with visitors), it is customary for the Indian nobles to bring the artist attached to the court to take the portraits of those present; the painter of (Maharaja) Shere Singh was therefore incessantly occupied in sketching with a black lead pencil those likenesses which were afterwards to be copied in water colours, in order that they adorn the walls of the royal palace, and some of these were admirably executed. I was among the honoured few and the artist was very particular in making a faithful representation of my uniform, my hat and feathers.”

— Leopold von Orlich, German visitor to the court of Maharaja Sher Singh at Lahore, 1843

Of great interest as this brief notice of painting in the Punjab is what I am writing here is neither about artists working for a royal patron in Lahore, nor about high-ranking visitors, nor even about portraits that might have been meant for royal walls. It is about an obscure group of portraits of people of no rank, none whatever; people who might never even have been anywhere close to a royal court. Even as paintings they are virtually unknown, despite my having written about the likes of these before for a ‘learned journal.’ But they are works of extraordinary warmth and sensitivity: compelling in their quality.

When I chanced upon them years ago at Patiala, these portraits as a group were in private hands, owned by a gentleman who claimed to have descended from a family of artists that used to work at Patiala, having migrated to that kingly town from the Alwar–Jaipur region of Rajasthan. They were lying in an unkempt pile of sheets of varying sizes, stacked in utter disarray: sad reminders of a collection. Some of them were stuck to each other; others were water-stained or bore traces of mildew; nearly all of them were frayed at the edges. The pile contained a miscellany of images: some copies of figures taken from European fashion magazines; some designs for elaborately carved furniture; some sketches from a Ragamala series and studies of animals. What caught my eye — and I photographed — however, were some leaves bearing small portrait studies, sometimes two or three on a page, with an occasional scrawled inscription in a corner, identifying the figure/s. They varied from very small heads, seen from a distance as it were, to full faces seen, intently, from close; some of them featured carefully observed details of dresses worn, others paid little or no attention to apparel and concentrated only upon the faces. There were no signatures; nothing indicated who had painted them. What struck me instantly, however, was on the one hand the intensity with which everything had been observed, and, on the other, that they were renderings of common men, no royalty or nobility figuring in the group at all. I could not easily think of anything of this order that I had seen in any collection, elsewhere.

There were, obviously, questions these portraits posed. They could possibly not have been commissioned works, the figures being those of people of evidently few or no means. Were these, then, ‘exercises’ by painters who wanted to keep their hands in trim even as they kept working for patrons of high rank on different subjects? Or was it that interest in the men whose portraits these were came from the intrinsic nature of the artists themselves, or the closeness they might naturally have felt with the people who they mingled with, knew from the inside, as it were? There are no easy answers to these questions. And, in the absence of these, one turns naturally to the works themselves. For, as I have said before, they are compelling.

…..

A Nobleman, late 19th century, Rajasthan, India, Ink and watercolor on paper, H. 14.5 cm, W. 10 cm, PTG.01101

I came across similar portraits in the collection of the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru. There is an image of a seated man, with no identification or inscription. Through the way he is dressed, in a Hindu jama with a coloured turban on his head and patka or sash around his waist, one can deduce that he is a nobleman, perhaps belonging to a royal court. With slight colour in the sketch, the artist has depicted the nobleman in profile with soft but stern features.

…..

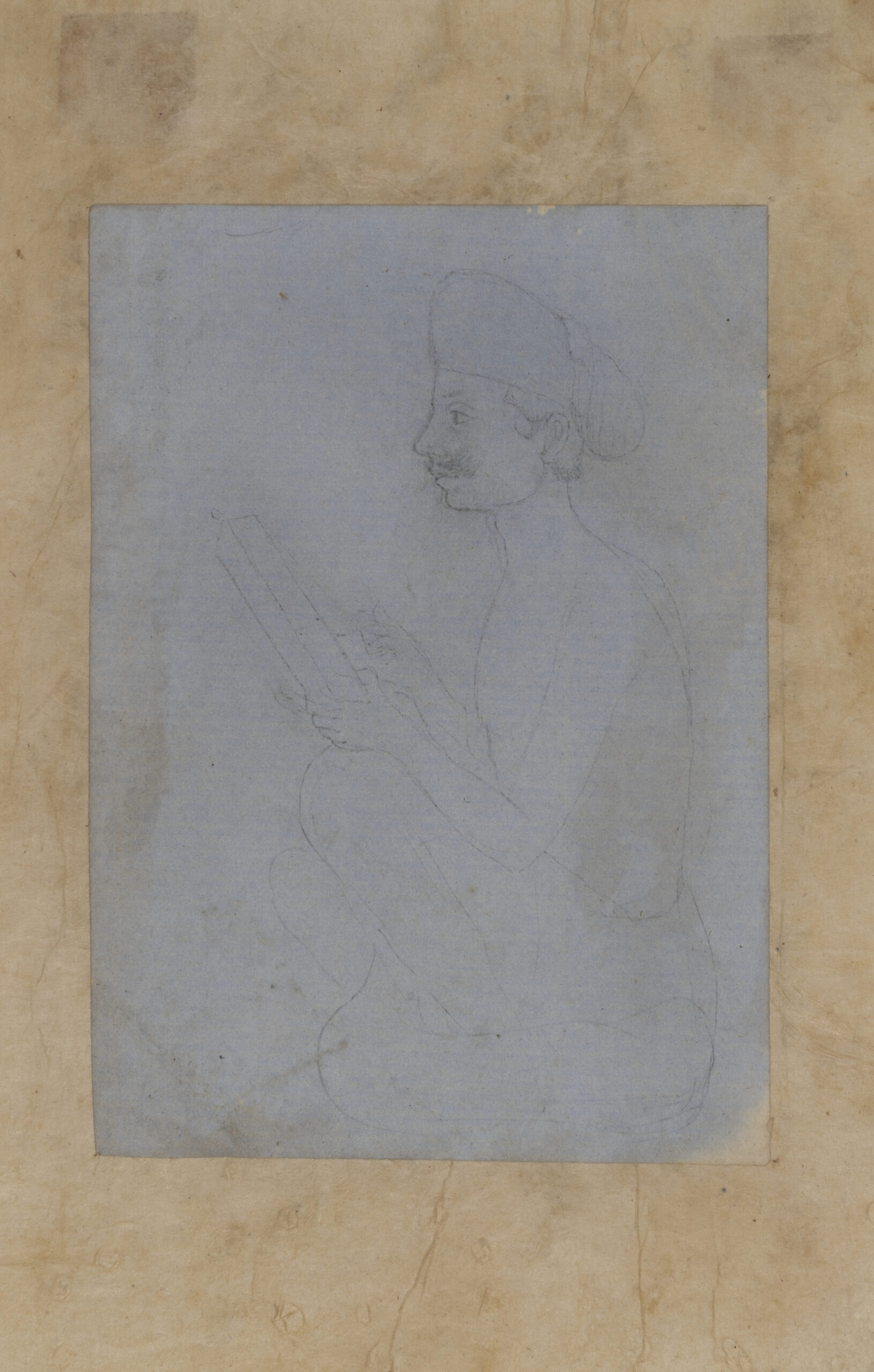

Sketch of a Musician, 19th-20th century, Rajasthan, India, Ink on paper, Object: H. 11.4 cm, W. 8 cm; Support: H. 16.5 cm, W. 10.8 cm, PTG.02008

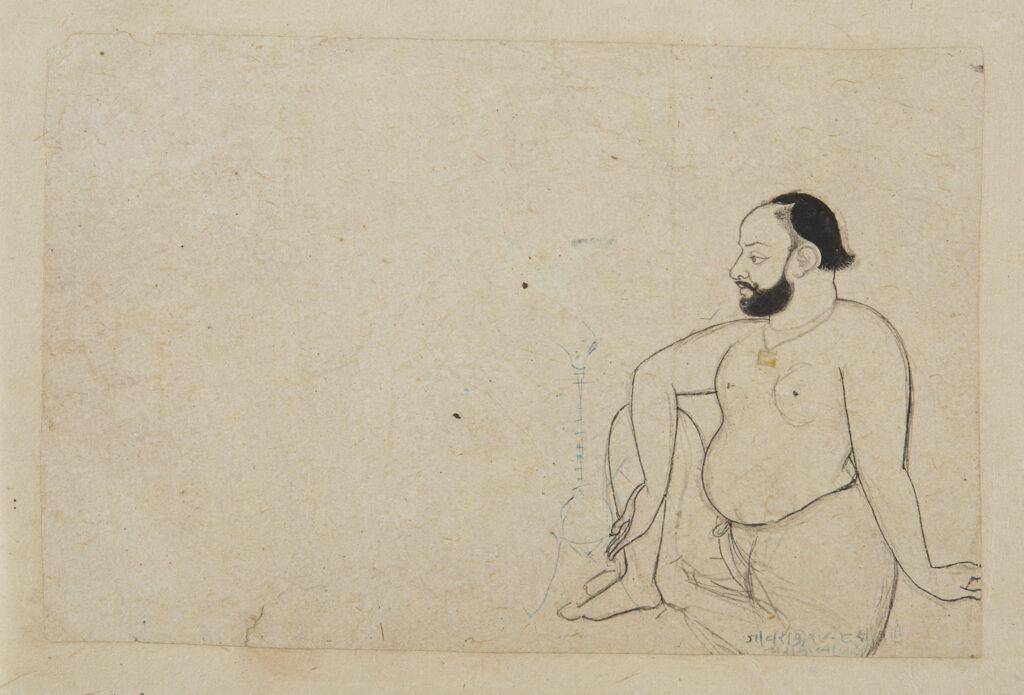

Portrait of a Nobleman, Chatera Ramlal, 1852 , Mewar, Rajasthan, India, Ink and watercolor on paper, H. 12 cm, W. 18 cm, PTG.01103

There is an almost faded sketch of a musician rendered in pencil on a stark white paper. There is also a portrait of a middle-aged man, who is depicted dressed in a dhoti with his upper body and smoking a hookah. With no identification or inscription, it is hard to say which class of society the man belonged to. One cannot at the same time escape the feeling that the man is, at this moment, somewhat troubled, for shades of anxiety, uncertainty hover over the face.

This is the way it goes in this extraordinary but neglected group of portraits: farmers, devotees, performers, small-time craftsmen, boys at the threshold of youth, men who have grown old dealing with the world. There is no fancy finishing in them, no frills of any kind. But in them there is warmth and honesty and remarkable penetration of character. Contemplating them is, at least for me, like moving into a zone where one can sense a whiff of fresh air brush past one’s cheeks, feel honest grit between the toes, smell the fragrance of the earth.

The essay was originally published in The Tribune, Chandigarh and it is being reproduced here with the permission of Prof. BN Goswamy and The Tribune. This has now been adapted to feature artworks from MAP, and thus slightly modified. The part that has been removed from the original essay is replaced by ….. and the part that is added to the essay is in italics, (to make it relevant to the images from MAP).

In another essay from this series, Prof. BN Goswamy traces the popularity of the camera in India during the nineteenth century. Read the previous essay, ‘Cameras and Colonial Encounters’, here.

Prof. BN Goswamy is an Indian art historian and critic, best known for his scholarship on Indian miniature paintings, particularly Pahari painting, and is the author of over twenty books on arts and culture.