Blogs

At the edge of the written: Observing Ravikumar Kashi’s “We don’t end at our edges”

Srinath G M

In Ravikumar Kashi’s recent exhibition, We don’t end at our edges, language becomes sculptural, paper performs like metal, and shadows speak as vividly as the forms that cast them. What might initially appear to be fragile tangles of paper pulp slowly unfold into a spatial grammar — dense with echoes of writing, place, and the material memory of handmade practices. Kashi’s work here is not simply about making objects, but about constructing a field in which form, language, and temporality merge and separate rhythmically.

The exhibition title carries an insistence that boundaries — of bodies, of speech, of media — are neither fixed nor final. Indeed, walking through the show can reveal how paper, one of the most ephemeral of materials, can become a medium for articulating questions of permanence and permeability.

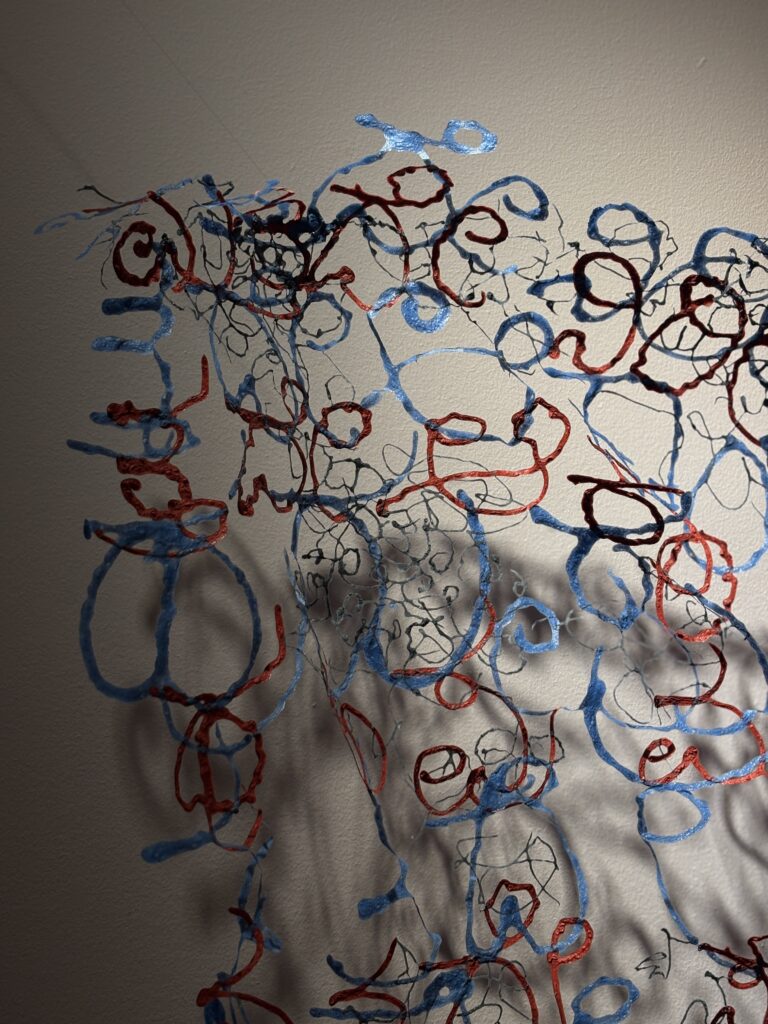

Kashi has long worked with hybrid forms of handmade paper, and in this series, his surfaces bear the traces of pigmented cotton rag, hanji, and Daphne fibre pulp — materials rich in both ecological consciousness and cultural lineage.

These fibres, far from being mere substrates, actively shape the aesthetic and conceptual language of the pieces. What emerges is a vocabulary of folds, loops, and interlacings, as if the artist is writing without a pen — drafting instead with shadow, tension, and suspended mass.

Kashi’s forms are built out of letterforms, but this linguistic scaffolding resists readability. The text is not designed to be deciphered; it’s there to be inhabited, seen, and sensed. Standing in front of one piece, I found myself tracing the looping forms almost unconsciously with my eyes, as if following a current — a sensation closer to listening than to reading.

The script — often curved, looped, and marked by vertical symmetry — finds an uncanny visual parallel in the lace-like textures Kashi creates with paper pulp. These aren’t just decorative repetitions; they behave more like semiotic residues, fragments of a language that refuses to resolve into easy communication. Language here is at once intimate and estranged, echoing Kashi’s own multilingual engagements and his deep investment in the act of writing as material and metaphor. In dissolving the readability of the script, he draws attention to its body — to the glyph as gesture.

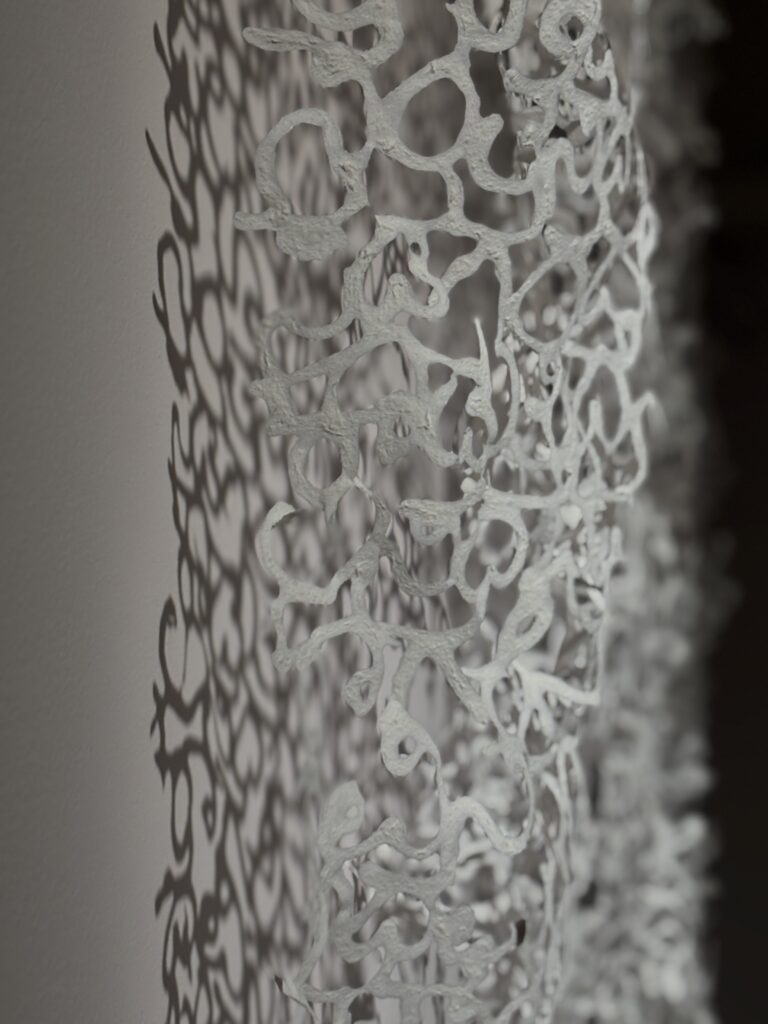

This material writing is further expanded through Kashi’s orchestration of light and shadow. Almost every piece in the exhibition is lit in such a way that each sculpture seems to emit as much as it absorbs. The shadows stretch, multiply, and distort the forms, sometimes overtaking the sculptures themselves. At times, the shadows create ghost texts — phantom versions of the work — that shift as the viewer moves. What begins as a lattice of paper becomes a mutable architecture of language and light, oscillating between the visible and the nearly vanished. This play of shadow is not ornamental; it becomes a critical dimension of the work, a kind of afterimage of thought.

One of the most striking visual strategies in the exhibition is the use of colour as a sculptural agent. Vivid oranges, intense cobalt blues, and earthen rust tones are not applied as surface treatments; they are embedded within the pulp, forming chromatic textures that suggest both geological layering and linguistic sedimentation. The colour does not simply cover the paper — it inhabits it. Some works feel almost coral-like, as if they belong to an underwater terrain or a molecular scale, defying conventional readings of paper as flat or insubstantial. These colours punctuate the otherwise muted palette of the show and reorient the spatial dynamics of each piece — pushing and pulling the eye across their surfaces, inviting intimate inspection and long viewing. As I leaned closer, the textures and embedded colours made me think of eroded landscapes, ancient texts worn by touch — a strange feeling of both deep time and fleeting presence.The tension between structure and dissolution runs throughout the show. In many pieces, what might once have been a cohesive script has unraveled into openwork webs. The edges of these forms are not borders but zones of diffusion. This is where Kashi’s most compelling ideas surface — in the refusal to close a form, to finish a thought, to finalise a boundary. The edge, for Kashi, is not a site of termination but of continuity. What looks like disintegration is actually the moment of transformation — from letter to lace, from form to field, from word to world.

One wall text in the exhibition speaks of paper as a “metaphor for porous boundaries: between self and world, text and form, presence and disappearance.” This sentence might well summarise the affective core of Kashi’s works. They perform a politics of in-betweenness, insisting on liminality as a generative space. The suspended sculptures — many of which float just off the wall or floor — seem to be in a state of constant becoming, never fixed, always tentatively asserting their presence. This ambiguity is not indecisiveness, but a deliberate aesthetic stance that resists closure.

These works also index time in ways that feel intimate.

According to the curatorial note, Kashi worked over 22 months on this body of work. The slow, almost meditative process of forming paper pulp, drawing script, and letting structures dry into their final shape became a tactile form of journaling. This durational quality is embedded into the surface of each piece. Nothing is hurried, and everything bears the mark of having been made by hand — a quiet ethic of slowing down that feels especially radical in a moment obsessed with speed and immediacy.

What also stands out is Kashi’s refusal of monumentality. Though some works reach the scale of the human body, they never dominate the space. Instead, they invite movement, encouraging the viewer to circle, approach, and crouch. These aren’t works to be seen in a glance; they require time and bodily negotiation. In that sense, they are not just visual objects, but environments — spaces where attention is both demanded and dispersed.

Finally, it’s worth noting that Kashi’s training across multiple disciplines — painting, printmaking, literature — is deeply visible in this exhibition. The works sit somewhere between drawing and sculpture, between writing and weaving. They are neither illustration nor abstraction but a third space, where the act of meaning-making is both the subject and the method. His “lab,” as he calls his studio, is not a site of invention in the industrial sense, but one of iterative discovery, of returning to the same form until it frays into something new.

In We don’t end at our edges, Ravikumar Kashi offers no answers, no direct messages. Instead, he opens up a field of slow questions — about language, materiality, and the contours of presence. What does it mean to dissolve a letter? How does light write? Where does a form begin, and when does it end? These questions linger long after the viewer has left the gallery, like the soft shadows that remain even when the light goes out.

All artworks discussed in this piece are a part of the exhibition, We don’t end at our edges on view at MAP. The featured image of Liminal membrane was photographed by Krishanu Chatterjee.