Interviews

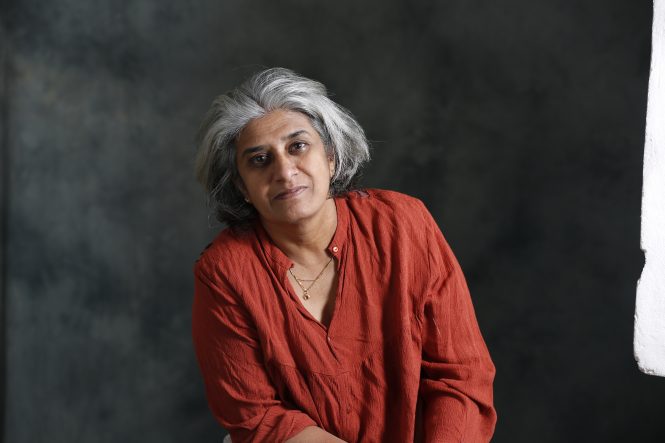

Materials, Memories, Meanings: In Conversation with Shanthamani M.

Krittika Kumari

Exploring the role of materials, memories and meanings in Shanthamani M.’s work through an exclusive conversation with the artist.

What prompted you to document the city and create the photomontages that are currently on display for MAP’s exhibition Past Continuous?

In 1993, when I moved to Bangalore after my post-graduation, there were a few other young artists in the city like myself who had just returned from different art education centres, mostly from Baroda, Shantiniketan and Delhi as there was no other institution which had higher studies in visual arts. As artists we all came back with ideas and hopes, but what we discovered was that there was little to no structure or gallery support for an artist at that point of time. We all would get together in the evenings and wonder how we can make a difference to the cultural scene in the city. We wanted and needed to prove that artists play an important role in a society so a lot of our work in the late 1990s was connected to social issues.

Then in 2006, we saw a rapid change in the city landscape and I particularly felt it was important that we documented because it looked like we may not see that space again; we may not see the different colours and textures of the city, or the costumes and festivals. Documenting the city of Bangalore as it was, and its people, felt like an urgency. Bangalore was becoming a city that garnered a lot of global attention and was being developed with the best infrastructure in the country. However, I wanted to also uncover the other side of this development – of its impact on the community and the different sectors in the city.

It was almost as if the entire focus was towards the software industry, but how was that really affecting the overall landscape of the city? Bangalore, for me, became a great opportunity to understand the development process of a city. Many cultural places shrank during that particular time and as a cultural practitioner, it was imperative for me to document this change.

Photomontages by Shanthamani M, 2006-2008, Bangalore, India, Image courtesy of the artist

Why the title ‘Past Continuous’?

The title references the constant practice of throwing things against each other – native versus outsiders, vernacular versus global, tradition versus modernity. The photomontages too explore these dichotomies and conflicts, and continue the debate of the past versus the present. So the title ‘Past Continuous’ seemed apt.

Can you tell us a little about your installation titled Backbone for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2014? What were the challenges you faced given it was your first outdoor sculpture?

When I was invited by Jitish Kallat to participate in the Kochi-Muziris Biennale back in 2014, I instantly knew what I wanted and needed to do. I had already displayed a version of Backbone in charcoal earlier in 2012 for the River, Body & Legends exhibition at Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi. For that show, I, along with two other women artists, travelled along the Ganges, from Gomukh to Gangasagar. We began at Allahabad and travelled all the way till Farakka Barrage in West Bengal and this was a very creatively enriching experience for me. It was here that I realised that Ganga is actually the backbone of our lives, of this country.

Shanthamani M.’s works from the ‘River, Body and Legends’ series, shown as part of ‘Reflections’ at Cinnamon, 2012, Photo Credit: Mallikarjun Katakol

Rivers have always been the backbone of civilisations; people even today rely on this river for several reasons, economic and mental. So when I read Jitish’s curatorial note for the Biennale, I felt this work would actually work really well as I wanted to showcase the intrinsic relation between human beings and nature, and more importantly the impact of water on Kerala’s people and cultures. The river Ganga, and subsequently the backwaters of Kerala, became the backbone of my idea and the spinal cord-like installation I created for the Biennale using cinder and cement. The challenge lay in the fact that I had never done an outdoor installation before but I think my curiosity and passion for exploring materials and new modes of display helped me drive the idea forward.

The installation also had to connect with the display location, which was Aspinwall House in Kochi that overlooks the sea. I wanted the artwork to feel and look like a creature that has just crawled out of the water. For me, the legs of this installation reference the many people, whether soldiers or traders, who have walked onto this land from the water. I wanted the installation, much like the land it stood on, to be an object of debate, reflection and exchange.

Backbone by Shanthamani M., 2014, Cement, Steel mesh and Cinder, 6 x 72 x 5 feet, Kochi Muziris Biennale, Photo Credit: Mallikarjun Katakol

How and why did you choose cinder and cement to create this installation?

My material usually evolves with content, so initially it was a challenge to envision what material I should use for the Kochi installation. My concern was to use a material that aptly conveyed my idea about the river Ganga being a rejuvenator of humanity, of civilisation. I happened to come across piles of cinder that were being sold close to big construction sites in Bangalore. Cinder is nothing but coal – the coal that has been burnt and exhausted. So, it is kind of a dead material and is of barely any use. In construction, it is used to fill in sunken areas because it is a lightweight material, and I found this idea very interesting. A dead, exhausted material was being rejuvenated by bringing it into the creative process of constructing a building, or in my case, a 72-feet long installation. That is how the idea of working with cinder came up.

During the early part of your career, you created largely using materials such as red oxide. What is the significance of a material like red oxide for you?

Right after college, I began working with red oxide and primer, and that was purely because these were inexpensive materials and as an art professional right out of college, you don’t have a lot of money and resources to work with. So at that time my choice of material was driven by convenience and red oxide was highly convenient because it was cheap and lasted for a long time. At the same time, red oxide was also important because it is an industrial material and I felt it would be apt to speak about issues of development and industrial waste.

When I moved to Bangalore in around 1993, the city was just shifting towards becoming electronic, and the rapid urbanisation was almost just beginning. I saw a huge amount of motorcycle waste that was being sold at a junkyard in Shivaji Nagar, and this was all a bit of a cultural shock for me as I had just moved from a small city, having grown up in Mysore and studied in Baroda. On seeing these man made objects lying in a junkyard waiting to be recycled, I realised that there is perhaps a parallel between how these exhausted objects interact with the space they inhabit, and how human beings interact with each other in large, dense cities.

The more time I spent in the city during this time of urbanisation, the more I realised that this progression wasn’t always necessarily a cause for celebration. So this question of environment and development sort of began brewing in my head between 1993 and 1995. This is another reason why I started working with a material like red oxide.

What is your artistic process? Does the material come first, or the content?

I can now say that very early in my practice, I realised how important the synthesis of material, content and intent is when creating an artwork. Even though I’ve trained as a painter, I decided that the medium was not always going to be able to communicate my ideas and message. It was important for me to bring in material that would go well with my vision. Since then, I’ve worked with a range of materials, which are chosen either because of the message, or the location of the artwork. It’s also interesting because I think material brings its own history and identity to the work too, which makes for a compelling narrative. Initially, I was fixated on bringing two things that I like, for instance the content I was thinking about and the material I wanted to work with, together. However, now since I’ve been working with materials for so many years, I guess I can say that in many ways the material journey plays a more prominent role in my artistic process than the content. The material can easily add more layers to the content of an artwork, and can make it more expressive. I now also understand materials really well and it’s easier for me to conceptualise content around a material. For instance, I’ve been working with charcoal for the past 14 years, so now I know what kind of forms it can take and what the material can produce.

Hands by Shanthamani M., 2010- 12, Wood charcoal with cotton rag pulp, 30 x 36 x 63 inches, Photo Credit: Mallikarjun Katakol

Can you tell us about your time at Baroda and how it impacted your work and career?

Baroda was, mentally at least, a very ambitious period for me. When I did my BA in Mysore, I was part of the first batch in the college. So, my peers and I had almost no idea what it means to be living the life of an artist or a creative person. It was something that we couldn’t even imagine; it just had to be experienced. For me, that experience and reality came through when I went to M.S. University in Baroda for an MFA in painting. Baroda, as a city and MS University as an institution, was richer culturally, which is what I really enjoyed. In terms of art, however, there wasn’t that much that changed or came about in my work. This was a period in my career when I was hungry for experience; I wanted to learn everything and sometimes when you’re in that frame of mind, it becomes hard to identify what you really want to do or the kind of work you want to create. You want to just learn and think.

But the more important impact Baroda had on me was that, for the first time I saw women who were extremely independent, educated and focused on their practice. There were so many women who were pursuing their PhDs at the University, and this was just such a change from the environment that I grew up in, of seeing girls get married between the ages of 12 and 16. To arrive at a place where women actually had their own mind, and the courage to pursue their talent and passion was a truly eye-opening experience for me and impacted me greatly. It really changed the way I looked at my life thereafter. I also had the wonderful opportunity to interact with Rekha Rodwittiya who was my mentor and my guardian for the time I spent in Baroda. I was inspired by her because I think she was an artist that really broke the barriers and notions of what women can do.

I took my own time to find my voice and myself after Baroda, but I definitely came back with a lot more confidence by just knowing the possibilities that there were for me as a woman. The experience was very empowering. In fact, I still speak to Rekha about the impact she and this period had on my work.

Artist Shanthamani M., Photo Credit: Mallikarjun Katakol

Why did you choose to study papermaking at Glasgow under the Charles Wallace Scholarship?

By the time I went to Glasgow, papermaking was not offered as a course anymore at University; however some teachers like Ms. Jacki Parry agreed to teach me and allowed me to practice in their studio. I was already working with paper before I went to Glasgow but I didn’t know how to make paper the right way. I used to pick up techniques from traditional practices of using paper pulp for creating artefacts. For instance, in the villages, they grind newspaper with fenugreek to create a paste and use this paste to protect objects made of wood and cane. I’ve always been a very tactile person so this entire process of creating a paste, adding colour and then creating a work out of it was something that I enjoyed thoroughly. So while I had experience of working with paper pulp, I never actually knew how to make paper, which is why when I won the Charles Wallace scholarship I decided to go study papermaking in Glasgow.

Untitled by Shanthamani M., Cotton pulp body cast and watercolour, Photo Credit: Mallikarjun Katakol

Given that you have an MFA in Painting from Baroda, when did you actually pivot to creating sculptures and installations?

Although I’ve trained in painting, I have always leaned more towards working with very tactile surfaces and forms. Paper, in fact, provided a good transition for me to move from creating two-dimensional to three-dimensional artworks. This is because paper in its pulp form is three-dimensional and one can turn it into anything. It is also a softer and more malleable material so experimentation with creating sculptural forms was fairly easy. When I first started creating three-dimensional forms I did not have any knowledge of sculptural or carving techniques. So, I would say the pivot or transition was gradual, and that paper helped me move from surface to object.

Fire-script Landscape by Shanthamani M., 2017, Burnt wood, Plywood with steel frame, 72 x 72 x 6 inches, Photo Credit: Mallikarjun Katakol

What is your favorite memory of Bangalore as a child or young adult?

I grew up in Mysore, but I used to visit Bangalore very often from 1983 onwards. Between 1983 and 1985, I would say some of my most favourable and impressed memories are of walking on Brigade Road and seeing young people wearing jeans. At this time, we were dealing majorly in garment export and so there were all these rejected garment pieces that were accessible to people in big cities. In those days, seeing people wearing all different kinds of clothing, Bangalore looked like a different world altogether.

I also remember seeing a bunch of young people sitting on the pavement and playing their guitars – something that was so common in the 1980s but that I can’t even imagine now!