Blogs

Forbidden Souvenirs; or Extraction as Artistic Method

Rahee Punyashloka

This essay is a part of the booklet that accompanied the exhibition, The Forgotten Souvenir.

The first thing one notices when encountering the mica paintings is the rich, vibrant lustre of colours that abound within, despite the fragility of the substrate which holds them. The stunning endurance of colour, despite the fragility of the material involved, suggests a unique quality that is not usually the prerogative of the common artistic object. One of the first things that the artistic object loses is its colour and sheen, before the deterioration of the surface itself. In this case, though, it seems to be the other way around. One can’t help but wonder how much of the enduring legacy of the Orientalist trope about India being a “colourful land” has been contributed to by these paintings, and their circulation as souvenirs within the tourist market.

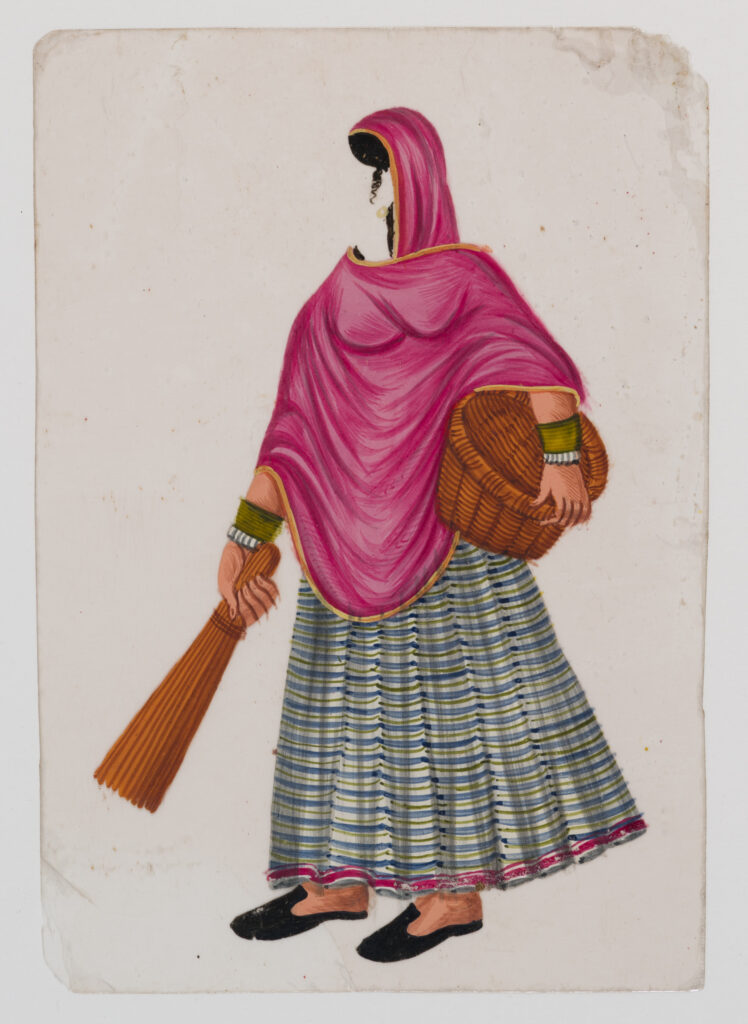

The capacity of the mica sheets to absorb and retain colours to a high degree has also produced another enduring legacy; one that far outlasts the paintings in question here, and continues till date – in the application of mica dust within make-up products such as blushes, to bring out exceptional vibrancy of colours on the human skin. So many of these colourful mica paintings survive without the faces that formed their backgrounds, producing a spectral realm of transubstantiation – where one must imagine the accompanying face, as if it were foregrounding one’s own face as an affectual remainder, to be installed, post facto. In this regard, these sans visage artworks are originary companions to the life-sized cardboard cutouts of photographs featuring famous personalities that abound in the current day. Even without the facial features that the mica paintings were originally supposed to come with, they can still be regarded as pioneering artworks with the curious logic that a displaced face can be substituted with a stand-in, as long as there is a recognisable body with distinctive markers present. The modernist myth of the faceless man is anticipated in extreme saturation here.

The chronicle of a colourful face as a “sublime object of desire” which requires mica as a material is aptly foretold through these sans visage artworks. The translation of mica from a surface (for painterly use) to a substance (for cosmetic use) raises a lot of questions around the artistic object and its objectives. The distance between the short-lived depiction of human (and anthropomorphised divine) bodies through the rich application of colours onto these sheets in the paintings presented in the exhibition here, and the sublimation of the material itself into an appliqué for the cosmetic enhancement of human skin paints a complex history of colonialist gaze, extraction and the cost of beauty.

The creation of mica as a viable painterly surface coincided with the British colonialist discovery of the “mica belt” in the 19th century in and around the Chota Nagpur Plateau, i.e. in areas adjoining the current day Indian states of Bihar and Jharkhand. A large number of the extant paintings being made in Patna were thus, most likely, a function of proximity to the source material. By the time the British exited the subcontinent, the mica extraction industry was burgeoning, with an overwhelmingly large supply of the material to the global north directly coming from this belt.

The mining for this delicate material could only be done manually, by agile bodies that could fit into the crevices dug into the earth, and the enduring, dark legacy of this fact is what continues to haunt us till this day. The dark legacy being that the bodies deemed the most fit for this extractive operation were those belonging to children. Even now, the shadow of child labour involved in procuring mica from these mines looms large over the makeup industry. While a majority of the mines where the mica was procured from in the 19th and early 20th centuries have officially been shut, since the 1980s, there have been exposés time and again which suggest how the local middlemen who operate at the behest of conglomerates find workarounds to continue this cruel practice. Every major company involved in mica extraction puts out neatly worded corporate social responsibility statements which suggest plausible deniability, but the practice of procurement continues, in much the same way as it would have, when the mica sheets were procured for the artworks in this exhibition. Naturally, almost the entire population employed in this exploitative industry belongs to the lowest castes and tribes: people who do not find representation in the depictions of daily life within these paintings, for they have remained concealed in newer configurations, deep inside the mines. The paintings on display, then, perhaps conceal far more in their translucent, delicate lustre than they show. The mythology of daily life that they create through their subject matter performs a foundational fabrication: one that obscures, under the colourful depictions, the profoundly disturbing scenes from the underground.

Most theorisations about the purpose of art suggest that there is an unassimilable surplus that can be found within art objects, a surplus that suggests an openness toward endless reinterpretation, toward play, toward “ἀλήθεια” or “unconcealment.” But with the mica paintings, we seem to enter a whole new era of artistic production. One where the sole purpose of the artistic object, right from its materialist ontogenesis, to its afterlife as an object of synthetic nostalgia – its affect is determined through the mandates set by colonial machinery. Hardly ever, until this juncture of colonial operation, had the purpose of art been so thoroughly inverted.

Mica paintings, thus, are a unique artistic object in that not only is their content shaped by colonialist logic but also their very materialism and form. That is, these paintings were produced with colonialist patronage and target demographics at their heart – with an eye to comply with the Orientalist doxa of the newly established colonialist tourist market, to be employed as souvenirs. But the very foundational possibility of these paintings occurring as a viable artistic endeavour was also generated and facilitated by the extraction of mica for various purposes, that continue till date.

To this effect, it is perhaps more apt to see these paintings as desiderata, as “found objects” in the sense that contemporary artistic practices use the term, in the service of interpretative leaps radically divested from the manufacture of nostalgia that they initially intended to evoke. The task of the artist, in this case, can only begin with these interpretative departures by us, here and now.