Blogs

Why I Love Art: My Nani’s Tijori

Yukti Agarwal

My grandmother’s passion for Indian handicrafts and garments urged me to embark on my own love affair with South Asian textiles.

One of the earliest memories I have of my nani (maternal grandmother) is not of her, but of her sarees and shawls: from the simple cotton block-printed sarees she wore all day to the shimmering banarasis, sinuous chantillies and plush pashminas which made her look akin to some of the most graceful retro Bollywood heroines.

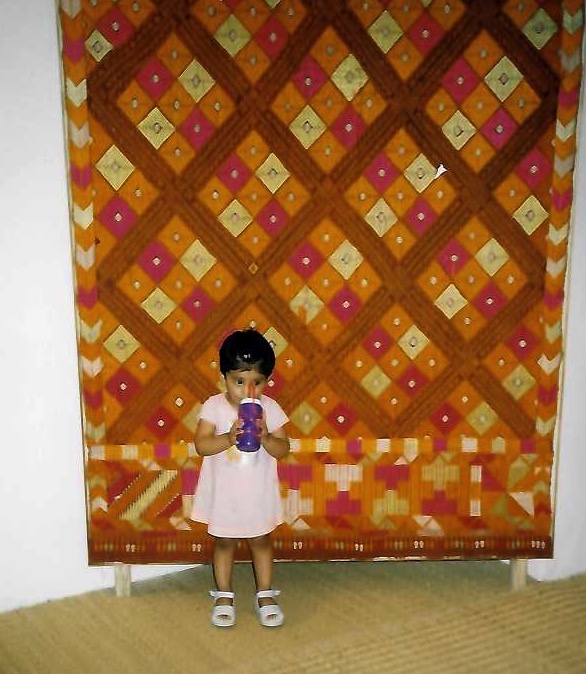

A vignette of a two-year-old me with my nani’s exquisite Phulkari, 2002, Photograph, Image courtesy of the author

Today, I find myself in the pristine study rooms of the Museum of Art at the Rhode Island School of Design studying some of the greatest feats of South Asian handicrafts. However, my exploratory research in South Asian textile arts started much earlier. At the time, I was completely oblivious to the fact that it was in these precious moments, wrapped in my nani’s arms and enveloped by her cascading sarees, that I received some of the most valuable lessons about the fibres, crafts and generational traditions which live in the weaves of the South Asian textile. Somewhere along the way, in the twenty-odd years that my nani took me to bazaars and melas all around India, I developed a deep love for South Asian textiles.

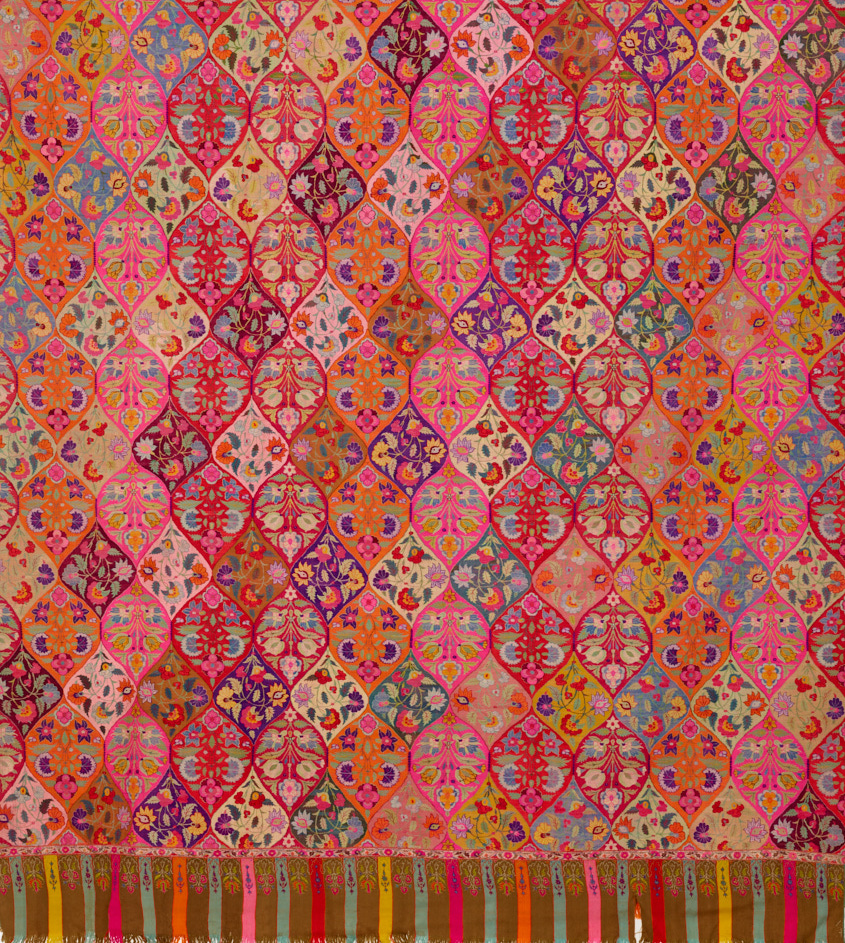

I had a particular attraction to the Kashmiri shawl. My nani had a tijori (chest) which housed her precious winter textiles. In the early months of winter, the tijori would open and I would see the painstakingly woven shahtoosh and pashmina jamawars and soznis clad my nani’s shoulders over her striped mashru silk sarees. My nani would take me to the annual melas of New Delhi, where she taught me how to identify the true fibres of the Kashmiri shawls; and so, the Kashmiri shawl became a quotidian part of my life.

Jamawar Shawl, Pashm, late 1800s – early 1900s, Image courtesy: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design

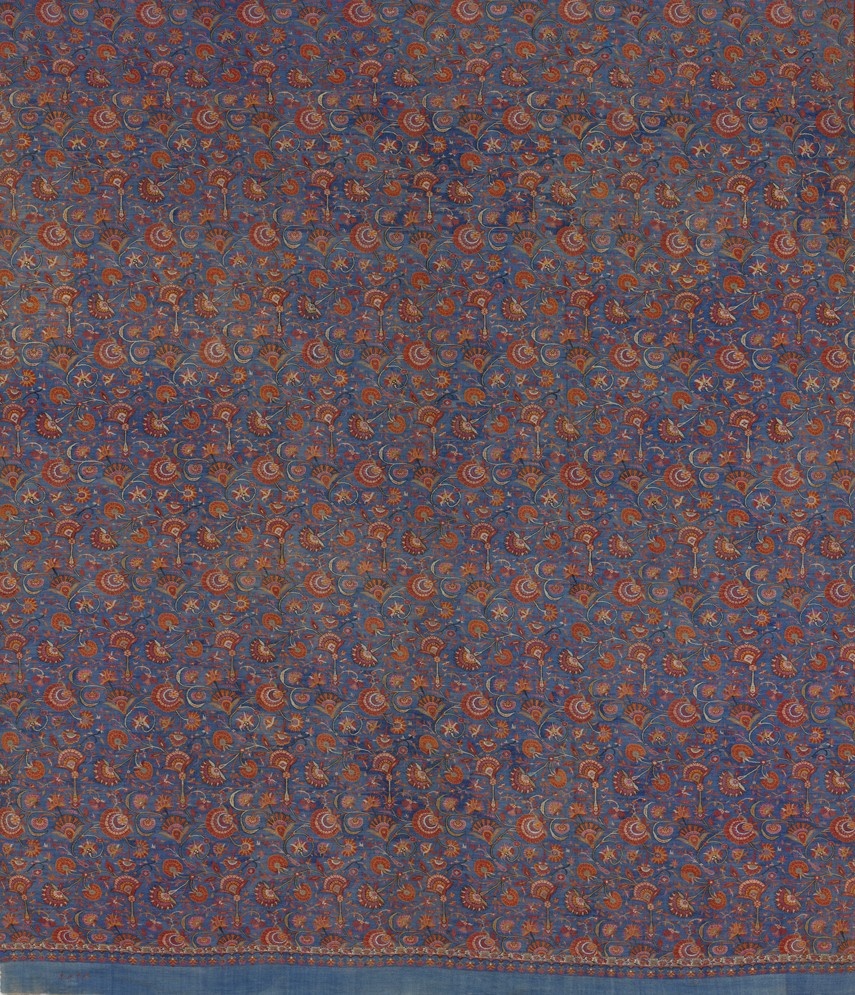

Oral traditions and other stories related to South Asia’s rich material culture act as living archives which grow each day as the old-time lovers of craft in South Asia shroud their bodies with these dossiers of culture and history. My nani’s stories, her experiences, and her eternal love for her collection of South Asian textiles reminded me of the importance of these lived stories, and the relevance of phenomenology in the study of South Asian textiles around the world.

Although my story begins with my grandmother’s tijori of precious textiles, this narrative will always be incomplete without the mention of the RISD Museum. Upon seeing the lonely Kashmiri shawls in our museum storage unit, I remembered what my nani had always taught me: each textile has a life, a story. I dug deep and unearthed some of the stories of these orphaned textiles at the RISD Museum, and recently curated an exhibit showcasing South Asian textiles that haven’t been displayed since their accessioning almost 70 years ago. I hope my research and efforts in showcasing South Asian crafts have resonated with those who visit the RISD Museum.

Jamawar Length, Pashm, late 1800s, Image courtesy: Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design

My nani is the reason I want to share these stories of South Asia and our textiles with larger global communities; she is the reason why I have this inexplicable love affair with any and every form of South Asian textile. Kudos to the woman who ignited a firing passion in me for the dying practices of South Asian textile crafts.

Yukti Agarwal is a textile designer, researcher, and social activist with an interest in museum studies, contemplative studies, and South Asian history. She is currently an honors student in the niche Brown | RISD Dual Degree Program at Brown University and Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island.