Blogs

6 Representations of Women in Art

Aayati Sengupta

In 1926, when the statuette of a woman was discovered in Mohenjo-daro, it was another addition to an already vast and varied body of artworks depicting women.

Women have been a popular subject for artists across centuries in all parts of the world. From early cave paintings to prehistoric sculptures to later works in textiles, living traditions, contemporary paintings and more, women have often served as creative inspiration. But were there no women artists? Or when painters were creating a piece did women have much of a say in how they were represented?

Take a closer look at 6 artworks from the MAP Collection — currently on view at Visible/Invisible: Representations of Women in Art through the MAP Collection. — to reconsider the role of women as both muse and artist.

1. Shadow of a chair by Arpita Singh

One of the key painters of Indian Modernism, Arpita Singh (b. 1937) grew up in an era when India had fought for and just gained independence. The myths and experiences of that struggle, as well as a sharp female perspective in an otherwise male-dominated artworld formed the foundation of her visual language.

Blue, grey, white and pinks form the colour palette of Shadow of a Chair – this oil painting by Arpita Singh. A woman lies on a white bed, her eyes open and her hand to her ear, as if she is listening to something. One cannot see a door but light falls on a patch of floor across from where the woman lies, casting a shadow of a chair in the room. A chair, carrying floral motifs similar to the woman’s dress, stands diagonally across from the woman, at the other end of the frame. Apart from them, the room has floating elements like a pistol, busts of women, head of a man, a vehicle, as if ingrained in the slats of the wall. A very thin line of blue runs across the top of the entire painting, symbolising something beyond the immediate confines of the room. Quiet and violence, rest and action, light and shadow are juxtaposed in the painting.

2. Mother Earth by Meera Mukherjee

Meera Mukherjee (1923-1998) was a trailblazing artist and researcher whose contributions expanded the lexicon of modern Indian art highlighting interconnections between the arts and social justice. Mother Earth, made in the same lost-wax technique as the statuette of the woman discovered in Mohenjo-daro, depicts the head of a goddess. Her face bears a placid expression, little leaves curl around her temple in lieu of hair, and the lobe of her ear is reminiscent of a vine-stalk. Mother Earth is cast in bronze, an alloy that’s created from tin and copper which is sourced from the depths of the earth. Mother Earth’s expression, the material used, as well as the labour-intensive artistic practice that Meera Mukherjee employed to create the sculpture is a reminder that strength and vulnerability coexist together.

3. Tell your children Ganga burns by Nalini Malani

“The kind of capitalism we’re experiencing has no concern for the Earth or the environment. It’s as if nature is infinite, but it’s not.” – Nalini Malani

Nalini Malani (b. 1946), a key figure in contemporary Indian art, has been instrumental in bringing the female gaze into a predominantly male-dominated art world in India. Growing up in a family that had migrated to India during Partition, Malani has spoken about how that history and experience marked her family, and her own life. These experiences can be seen seeping into her paintings which often focus on the experiences of the marginalised and disenfranchised in society.

In Tell Your Children Ganga Burns we see vast swathes of blood-red, alongside the orange-yellow flames of fire and blue-green of water. To the Indian mind, Ganga is firstly river and then, woman. But the deification of women has been so common and care-giving, life-giving attributes so often associated with the feminine, that Ganga’s burning can be read as violence not against just woman or river, but life itself.

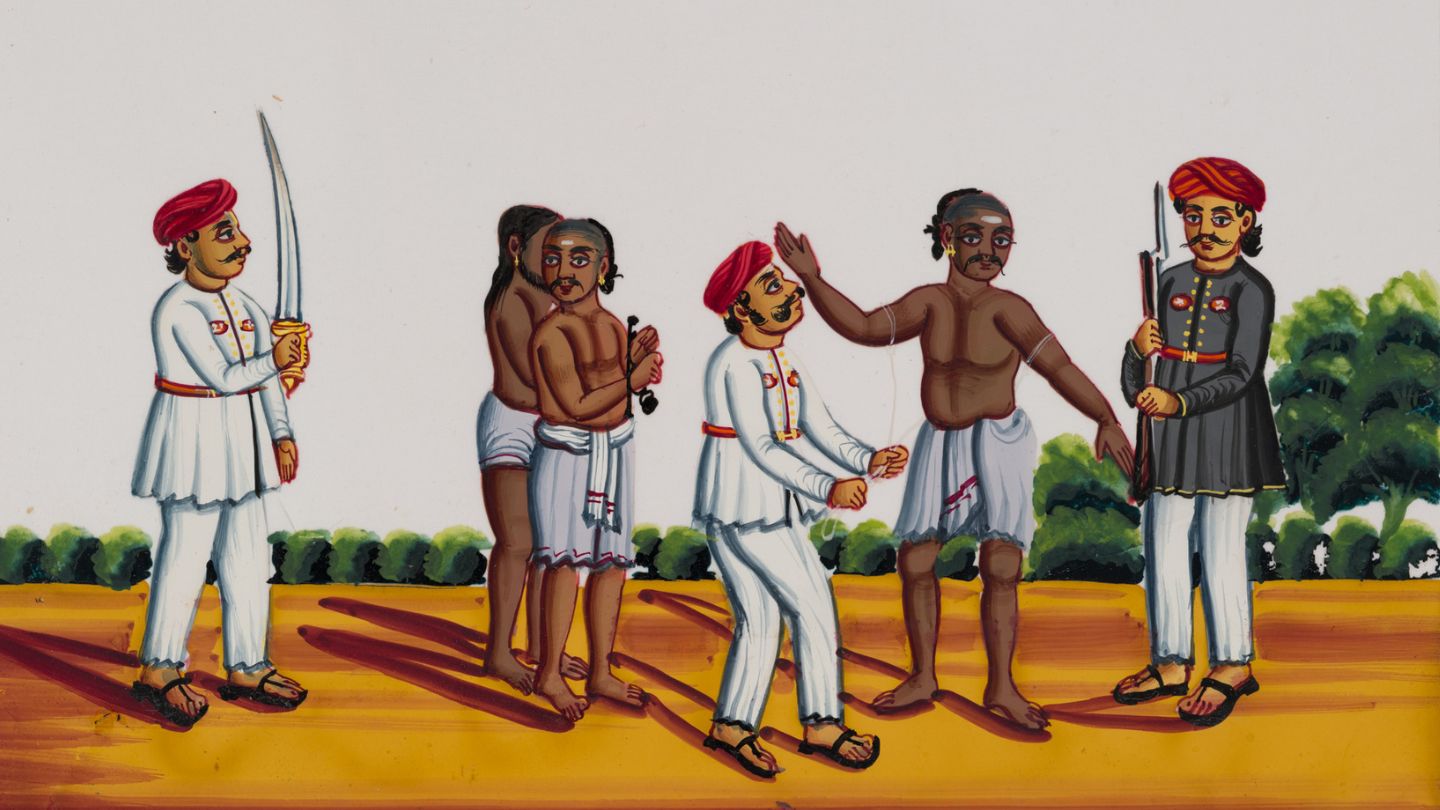

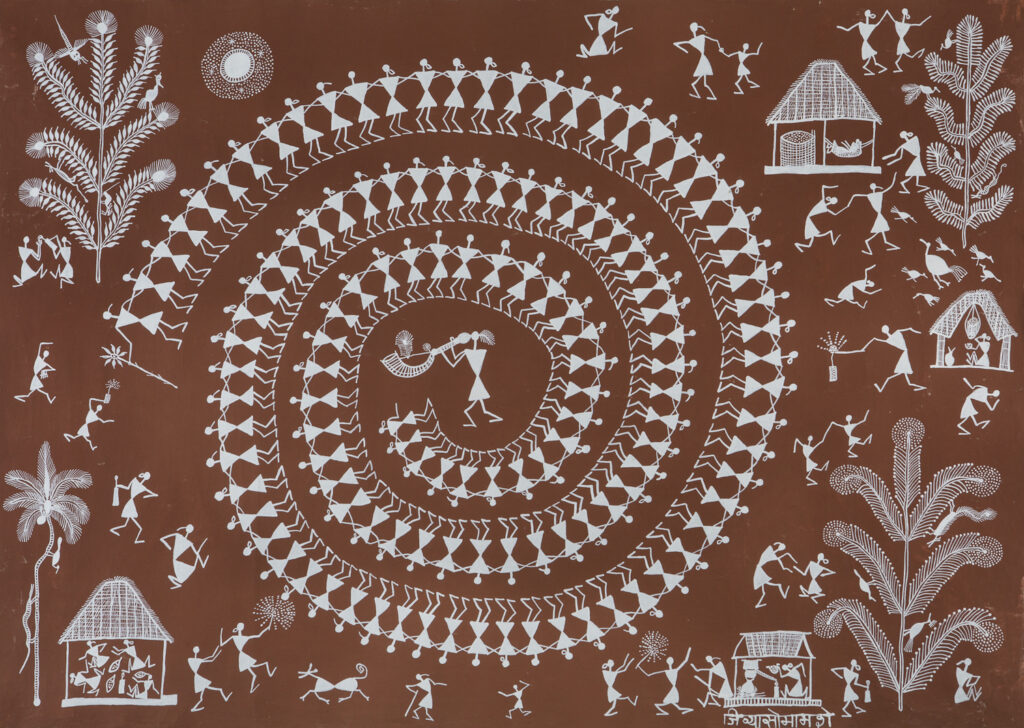

4. Untitled (Tarpa Dance) by Jivya Soma Mashe

Jivya Soma Mashe (1934-2018) was the first known painter to create Warli paintings on canvas. Traditionally, Warli paintings were made by women called Suvasinis on the walls of their mud houses with herbs and rice paste, and usually depicted fertility rituals.

When Jivya Soma Mashe lost his mother at the tender age of 7, he stopped speaking from the shock and instead, started drawing in the mud, reinterpreting the Warli visuals he was surrounded by. Over the years, he continued painting as a hobby and was eventually discovered by artist Bhaskar Kulkarni who helped bring his paintings to a larger audience. During that time, Soma Mashe widened his materials and tools to include canvas, cloth and artificial colours.

The untitled work, pictured above, is a painting of a community scene depicting the tarpa dance – performed by men and women in a circle around a musician who plays the tarpa, a very long wind instrument. Though Soma Mashe’s wife is said to have been the one who created the rice paste for his paintings, it was his growing fame as an artist that drew attention to this form. Do we find in this artwork then, traces of the female practitioners who came long before? Or a tale in which their voices have fallen silent?

5. Untitled by Jaya Ganguly

Jaya Ganguly grew up in an orthodox Brahmin household in West Bengal, more specifically, in the vicinity of the temple dedicated to the goddess Kali in Kalighat, Kolkata. Kalighat is associated not just with the Kali temple, but also sex workers, for many of whom the locality is their home. While the goddess is worshipped, the sex worker is seen as outcast. It’s these dissonances created by rigid patriarchal structures that Ganguly often explores in her works.

In this untitled artwork, otherwise vivid colours become part of a grim palette, and black haphazard lines run through the painting. The woman’s body, her tears and an undefined splash of brown and yellow that could be a couch are all fragmented by the black lines. Her face is in clear agony, teeth bared and her hair is open and dishevelled. This is not a conventional portrayal of a woman – as demure, neatly postured, politely smiling and well-dressed. Instead, it invites viewers to consider violence, rage, grief and anger as part of a woman’s lived experience.

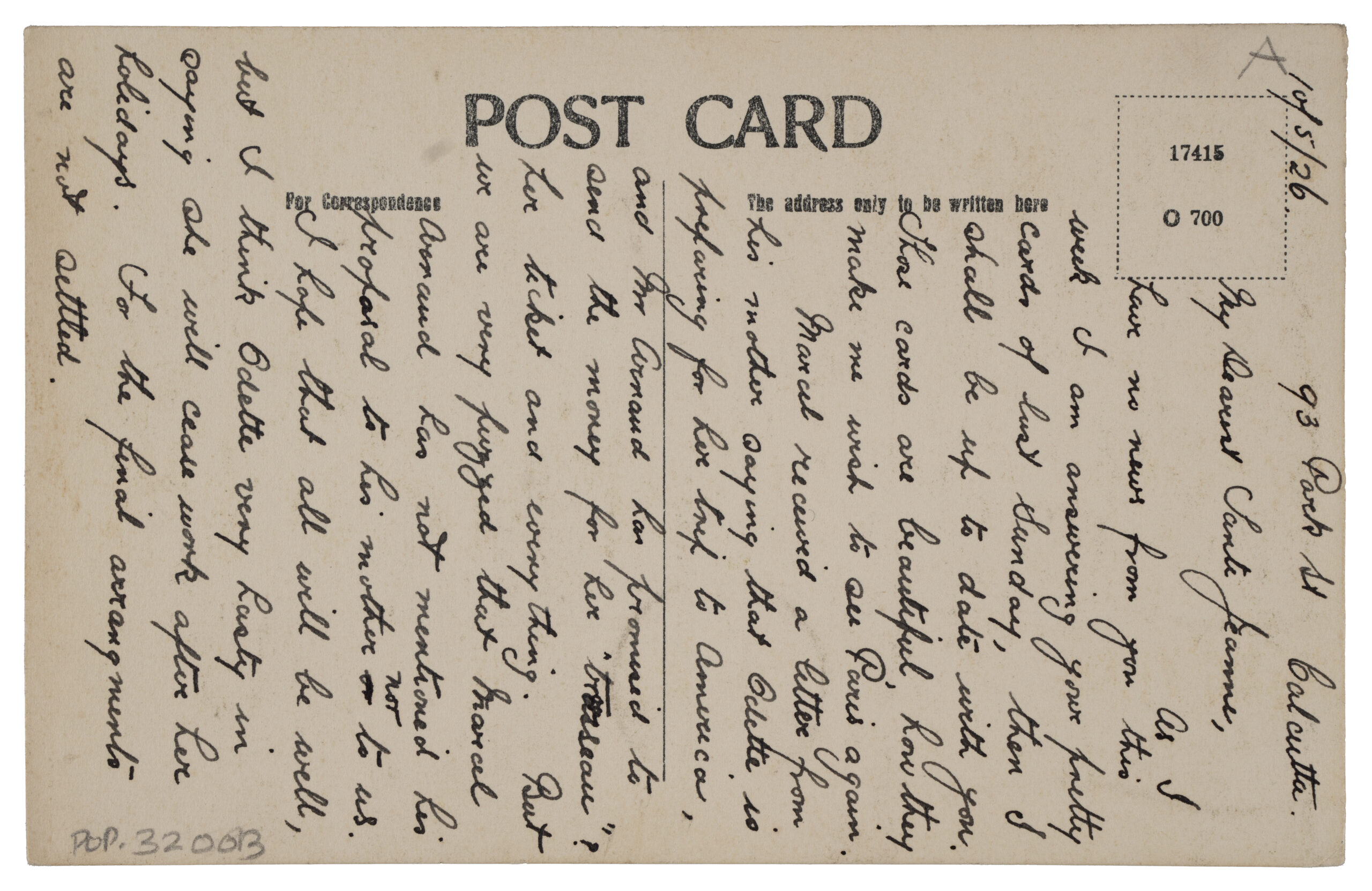

6. Untitled (from her autobiographical series) by Bhuri Bai

Bhuri Bai is a contemporary Indian artist, Padma Shri recipient, and one of the country’s first indigenous artists to come into mainstream prominence. Making Pithora wall paintings was something usually designated to the men in her community, but Bhuri Bai started creating them regardless. When she moved to the city to work as a construction labourer, she continued painting on stone. There, J Swaminathan chanced upon her works, and nurtured and encouraged her talent, providing her with paintbrushes and colours to continue her paintings on paper.

Part of Bhuri Bai’s autobiographical series, this Untitled work shows the moment when she started painting on paper. The domestic, the social and the cultural merge in the painting, where we see a child in a makeshift cot at the edge of the painting, women and men labouring some distance away, and a woman sitting and painting by the edge of a temple. The joy of everyday, mundane life is shown through the use of bright colours, the varied repeating patterns, and the smiles on the figures’ faces.

If you would like to know more about women artists in Indian art, you can continue on to Feminism in Indian Art.