Art reflects society. All art can be seen as mirroring the social mores, political realities and cultural contexts of its time. If not in subject, then in the manner of its production, or in the histories of its makers. Nowhere is this as apparent, as obvious, as in photography. The advent of photography in the 19th century irrevocably changed the way in which we viewed, accessed and understood the world.

With photography, the idea of art bearing witness to the passage and events of time took on a new shade of meaning – that of unaltered truth. From the 1920s onwards, as photojournalism grew in prominence, photography became a means to bring the realities of conflict and violence to the unaware, fostering sympathy, raising awareness or alternately offering critical commentary.

Today, we are all more aware than ever of how easily images can be manipulated. Yet we still believe, by and large, in the fidelity of a photograph that captures a single moment in time. This power that the photograph holds comes not just from what we see, or what is arresting and visible, but also from what we glean from it – the essence of other times, places and peoples that it reveals to us.

The Brazilian social documentary photographer Sebastião Salgado is known for his documentation of the human condition. Throughout his career, he has used his photographic projects to explore social and economic conditions in countries across the world, documenting the most isolated and neglected among us. This photograph forms part of a larger series entitled Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age that includes 313 photographs from 42 types of workplaces in 26 countries.

What I want is to create a discussion about what is happening around the world and to provoke some debate with these pictures...I don't want people to look at them and appreciate the light and the palate of tones. I want them to look inside and see what the pictures represent, and the kind of people I photograph.

– Sebastião Salgado

What hidden or neglected truths does art bring to life?

What confrontations does it force upon us?

Is art about never averting our eyes?

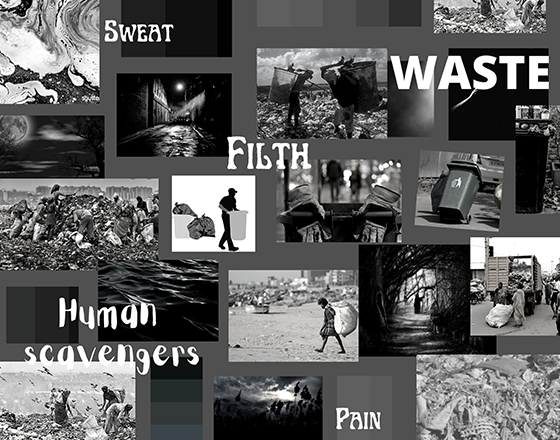

About 40,000 conservancy and sanitation workers are employed by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation. These workers collect the city's garbage, sweep the streets, clean the gutters, load and unload garbage trucks and work in the dumping grounds. Discovering the dehumanising conditions that they lived and worked in, documentary photographer Sudharak Olwe sought to tell their untold story.

What I saw shook me to the core of my being...filled me with rage and shame. My rage and shame, their faith and trust, these are the forces that have impelled me to ‘search for dignity and justice’.

– Sudharak Olwe

Sudharak Olwe's poignant photograph depicts the reality of the lives of 'modern' society's human scavengers. We, [as] privileged members of the societal order, cannot understand their suffering as attested by the photographer. It is too real for us, as mostly detached observers, to comprehend. However, this photograph provides a glimpse at the depth and darkness behind the 'pristine' world we see around us, through its raw quality. We wish to bring this reality to the forefront of society...depiction of books about sanitation in India, images of sanitation workers and moving depictions of the absence of light in their lives constitutes our 'board' of emotions.

How does art bear witness to the experience of conflict?

How does it shape our politics?

What aspects do we record, what do we remember, what do we reflect upon?

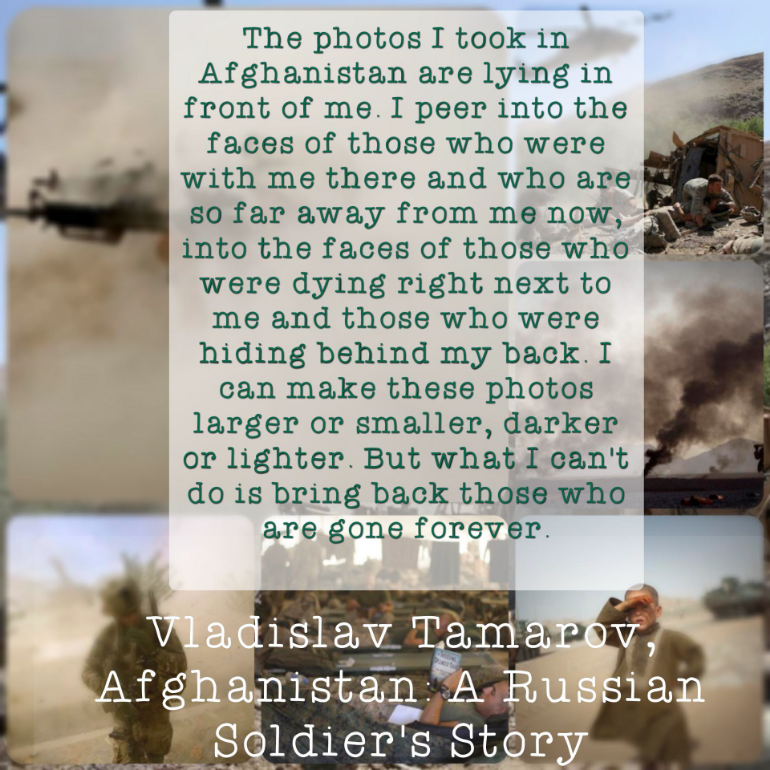

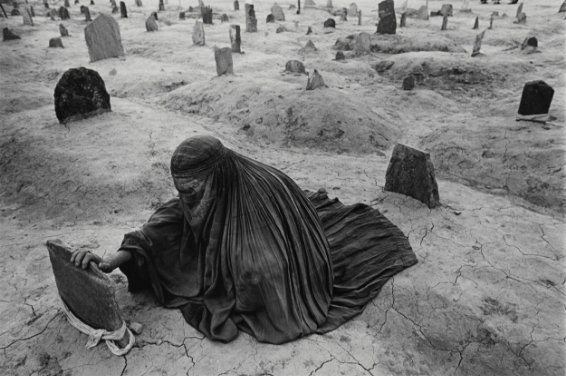

Robert Nickelsberg’s first trip to photograph Afghanistan was in 1988 – at the close of a failed ten-year battle against the mujahidin that the Soviet Army had fought. He continued to document the country for the next three decades which was to eventually come together as the book Afghanistan: A Distant War.

I witnessed repercussions of the political and economic chaos rendered by the Great Game, the end of the Cold War, the rise of Islamic militancy, and the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan by U.S. and NATO forces. – Robert Nickelsberg

Working as a TIME magazine photographer for nearly 30 years, Robert Nickelsberg specialised in documenting political and cultural change in developing countries. After covering Central and South America and the conflicts taking place there in the mid 1980s, he established his base in Asia. His work has also encompassed Kuwait, Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Indonesia and Iraq – capturing the incalculable toll that conflict takes on nations and people.

No outsider can fully grasp how the burdens of war are shouldered by individuals.

– Robert Nickelsberg

Since 1981, James Nachtwey has dedicated his career to documenting wars and critical social issues, motivated by the belief that public awareness is an essential element in the process of change, and that photographs of war can intervene on behalf of peace. He has photographed conflicts worldwide, as well as social issues such as homelessness, drug addiction, poverty and industrial pollution.

I have been a witness, and these pictures are my testimony. The events I have recorded should not be forgotten and must not be repeated.

– James Nachtwey

What do we see, looking into the eyes of the artist as witness?

What are the stories we read into artworks?

What lies beyond what we see?