The arts are an irreplaceable way of understanding and articulating the world – on par with, though very different from, scientific and philosophical approaches. It can be hugely transformative – in the lives of individuals, in communities, and even society at large. It has the power to effect change both in attitude and behaviour by enabling visionary thinking, initiating dialogue and facilitating the expression of personal experiences.

Art serves as a catalyst for social and political change both directly, and by prompting reflection and questions. Throughout history, art has transformed civilisations with its power to inspire, educate and impact us. It can spark revolutions and lead us on journeys to unexpected places and worlds. It speaks to our senses, intellect, emotions, imagination and even our memories. Art is not only at the heart of how we recall significant moments in history, but also a constant reminder of our humanity.

On 21 October 1967, almost 100,000 people marched on Washington, D.C. to peacefully protest against the war in Vietnam. In his last frame of the day, Magnum photographer Marc Riboud, who was documenting the march, captured a 17-year-old young American girl as she held up a flower to a row of bayonet-wielding National Guard soldiers. This image would soon be seen all around the world, becoming an inspirational symbol representing courage, pacifism and the power of nonviolent protest.

The target of our line of sight is reality, but our framing can transform it into a dream.

– Marc Riboud

Can art really change the world?

Can it alter how we view the world?

Can it transform our ideas of the kind of world we aspire to?

Ragamala paintings are meant to be visualised forms of ragas and raginis (the female counterpart of ragas) that evoke the same sensorial and emotional responses in us through the medium of the visual, as they do in their musical form. A raga in Indian classical music is a particular arrangement of notes. Since specific ragas are associated with specific times of the day, seasons and emotions, their representations are as distinct as their sounds. The Desakh ragini, for instance, is described in mood as fierce and energetic. Paintings of this ragini therefore spotlight physical prowess and strength, usually depicted in the form of acrobats, athletes or wrestlers.

[The] Desakh Ragini seems to remind us that our life is our own. She shows off her skills and passion, and encourages us to do the same.

This powerful message led to a spontaneous overflow of emotion and then poetry. Against the backdrop of this beautiful piece, is a sliver of hope that one day, women will have the opportunity to take pride in every step of their journey to success.

Does art show us a changing world?

Can it inspire us to change the world?

How does it push us to interrogate our values?

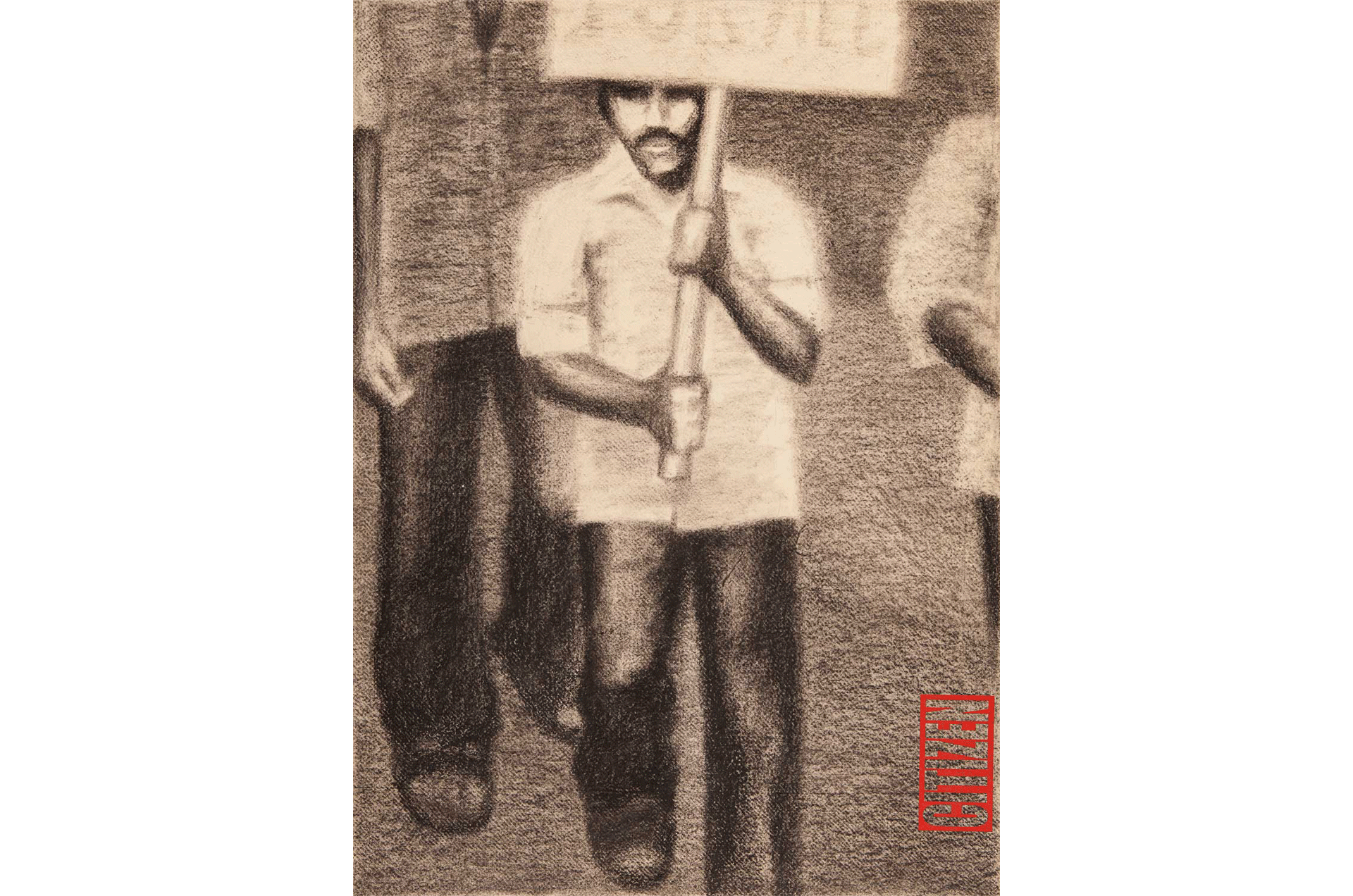

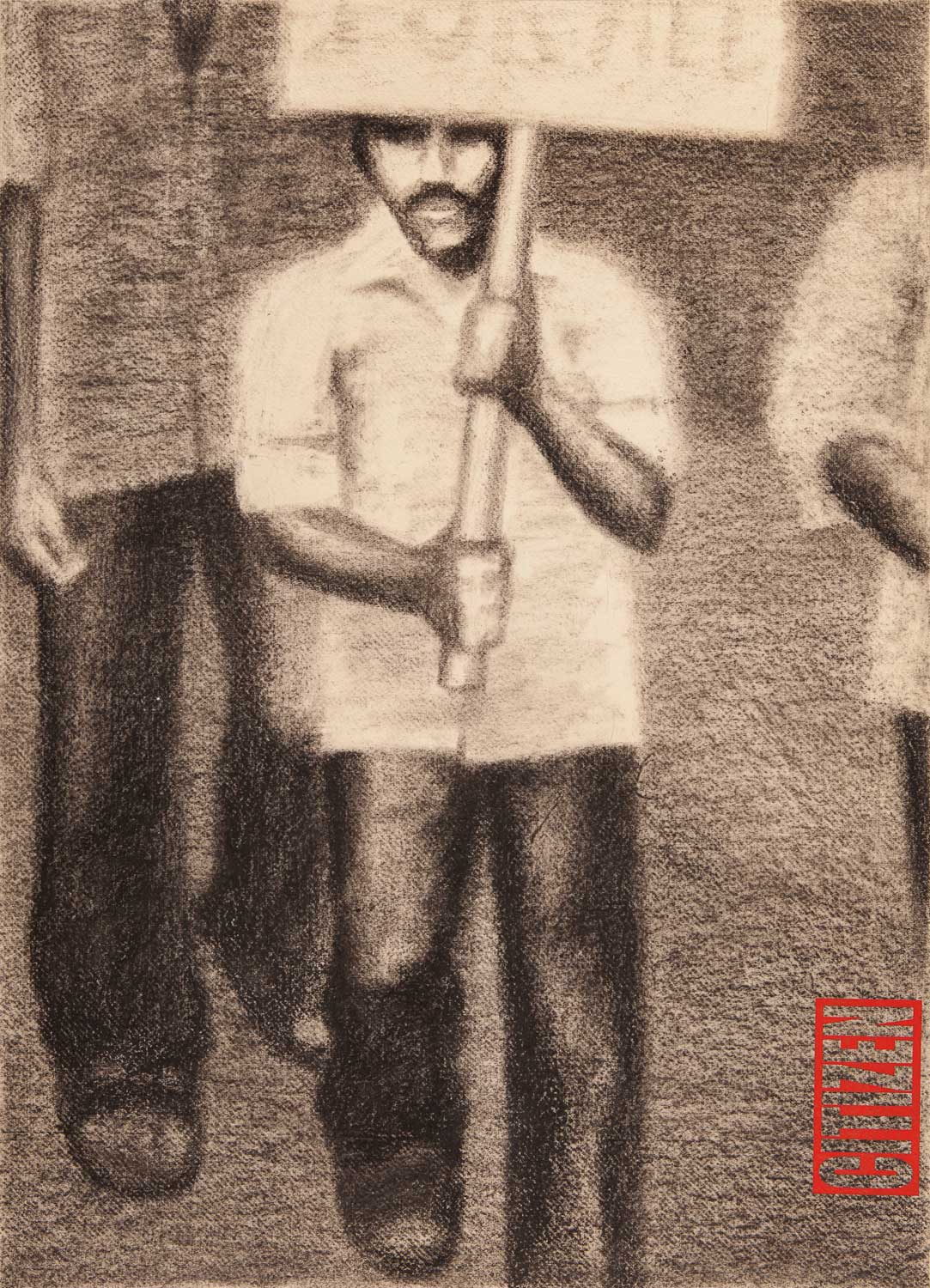

Rajan M Krishnan was a contemporary artist from Kerala, and a pioneer of the Kochi art scene. His art reflected the socio-political and cultural ethos he inhabited. Though his practice was primarily concerned with the environment and natural world, in this series titled Little Black Drawings, he explores questions of identity, nationhood, gender and labour, particularly in relation to political dissent. The charcoal drawings in this series were inspired by both personal local encounters and mass media images.

If I [had to] brand myself, I [would do so] as an artist with human concerns. I don’t brand myself as a political artist or an environmental artist. That’s there in my work. People must be able to read and recognise that...It is not the duty of the artist to claim such things. It is the duty of the people to understand that from the work of an artist.

– Rajan M Krishnan

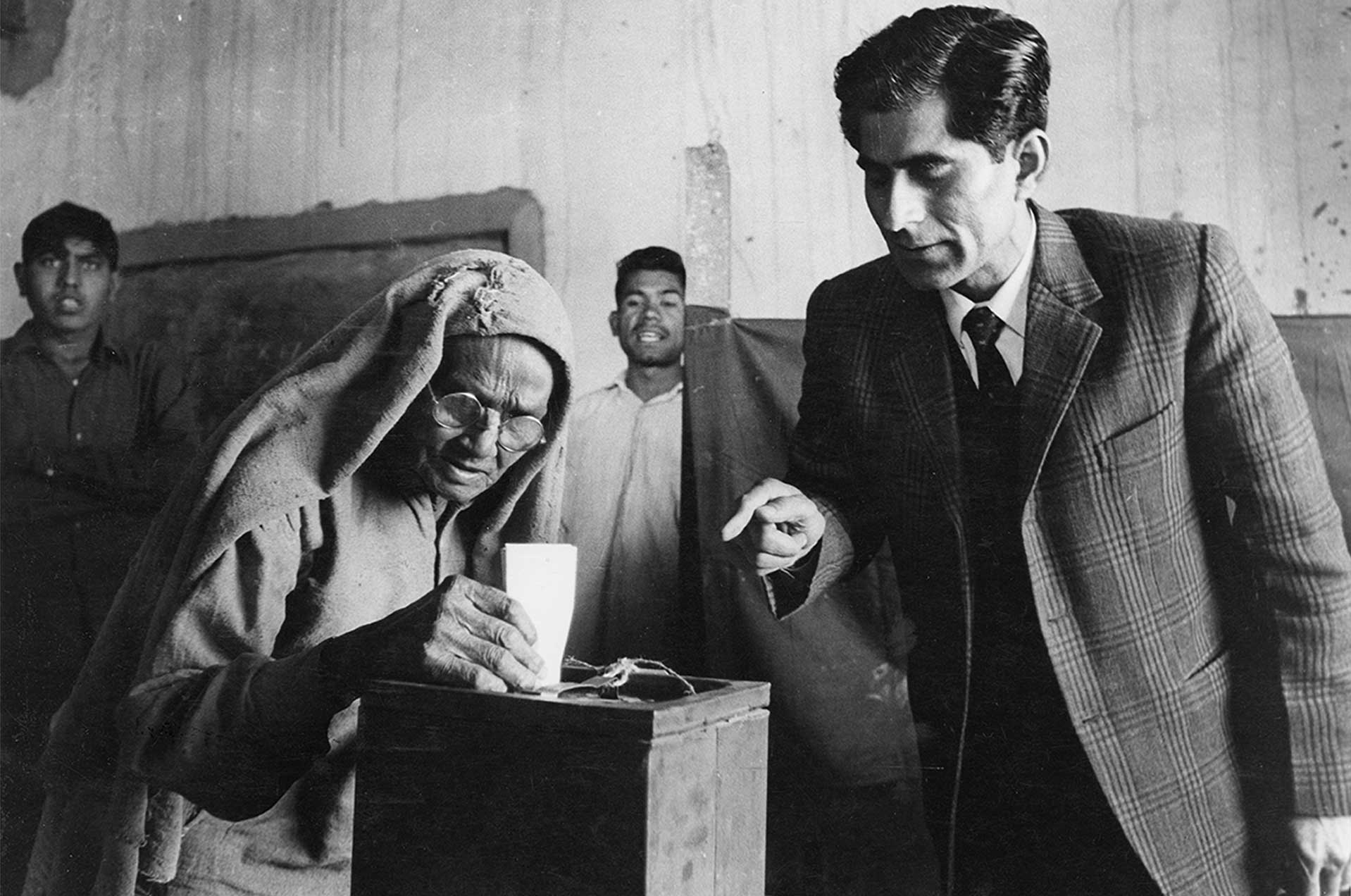

The photographs of T S Satyan, that graced several illustrious magazines, were often about the discovery of the extraordinary in the everyday. Featured in projects for the government and organisations such as UNICEF and WHO, they included everything from photographs of children to scenes of industrialisation. Through these countless slice-of-life images, Satyan documented a transforming country. This photograph, for example, speaks not only to new technologies by featuring the telephone, but also a changing world with a growing number of women in the non-agrarian workforce.

In its own unique way, a picture can activate the conscience. A sensitive photographer helps us ‘see’ what the eye has noticed but the mind has not absorbed...Without being preachy, he can sensitise, motivate and subtly show [us] the need to search our own hearts.

– T S Satyan

Where do we situate ourselves when we engage with art?

What are the stories we tell of what we see?

Can we respond to art by feeling, rather than observing?

Tambrahalli Subramanya Satyanarayana Iyer, popularly known as T S Satyan, is often called the ‘father of Indian photojournalism.’ His work is dominated by ordinary people going about their daily business, an account of the cycle of life: from birth through death. His photographs are witness to both interesting moments in modern history and the more mundane moments of everyday life; but his photographic style – gentle, intimate and personal – allows him to transcend the documentary and turns his images into expressive, emotive explorations of the world.

Photography is a wonderful way to explore the planet we live in. It is also a fascinating way to explore the human psyche...Great pictures are made, not taken...It is the prerogative of [the] camera to record the present as a reliable witness – and this is what is going to make photography a witness to the past as well as the future. Photography is history and life.

– T S Satyan

How does art inform our past, present and future?

How does it transform the political into the personal?

How does it transform the personal into the political?

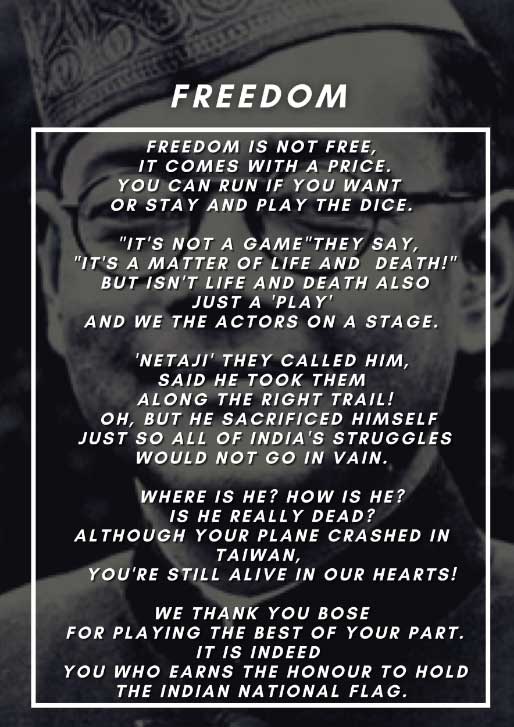

The expansion of lithography (an early printmaking process) ushered in an age of unprecedented mass circulation in 19th century India. Not only was it easy to now make multiple copies, the prints were also affordable and therefore more accessible to a greater section of the population. This led to them soon becoming vehicles for anti-colonial and anti-imperial narratives. Prints and posters of different kinds inflamed nationalist sentiment throughout the country – both by appropriating religious symbols or narratives and through representations of militant rulers or freedom fighters (such as this print that features Subhas Chandra Bose).

These mass manufactured prints often took on lives of their own. They were worshipped, embellished and used in collages, enabling a sense of ownership and creative consumption of art like never before. This new grammar of popular visual culture was to have a deeply transformative effect on the collective consciousness of people, an impact that popular cultural forms, such as the meme, continue to have even today.