Imagination is the supreme disrupter. Whether through photography, painting, film, music, dance, or other mediums, art provides a space for our collective imagination to take shape. This allows art on the one hand to play an essential role in illuminating, challenging and critiquing injustices, and on the other to also serve as a tool of propaganda.

Art is a key influencer: constantly shaping our perceptions of the world. Protesting policy, war or social norms, artists challenge the status quo and can often give voice to the voiceless and the silent. While some artists intentionally create works that respond to socio-political circumstances, other works may unintentionally speak to these ideas due to their histories or the context they’re viewed in. Whether subtle or forceful, art provides us with points of reflection, probing us to reexamine our understanding of the world and ourselves in it.

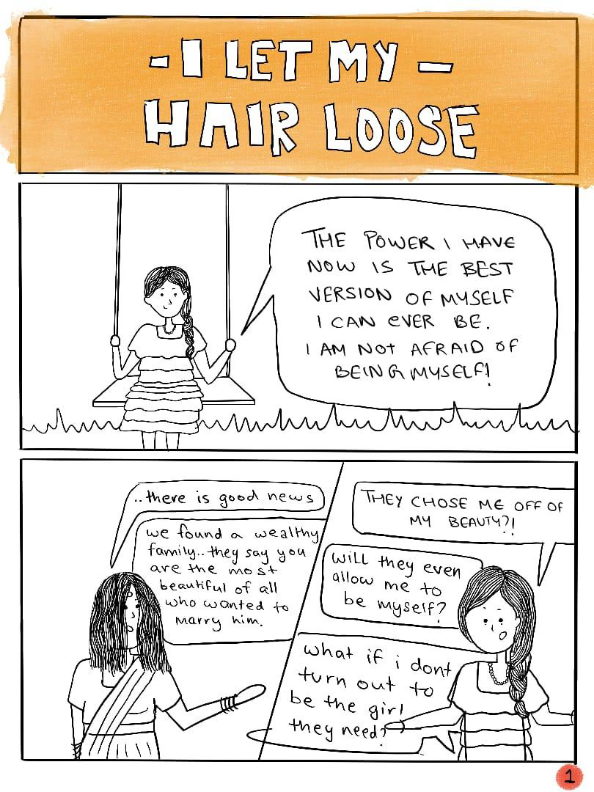

Anoli Perera is an artist who works with multiple mediums, often engaging with themes relating to women’s issues, history, identity and colonialism. In this photo-performative series, inspired by vintage photographs, she brings to the surface the politics of the ‘gaze’ by presenting women with their faces covered by hair. This act of defiance prevents us from looking at the sitters and causes us to reflect on the symbolism of hair. Hair is seen traditionally as a mark of beauty in women, but also—when out of place or unruly—as a sign of hysterical, uncontrollable behaviour, as a threat that reflects the dangers of unstable, untamed women.

My work has everything to do with the social predicament. It is easy to live through one’s life being unconscious of one’s context of existence. The very moment this existence is revealed, once you go beyond the illusions and its anesthetizing and doping images of representations, you are confronted with the maze of contracts and contradictions of that existence.

– Anoli Perera

What makes art a form of protest?

What are the stories we seek to rewrite?

How can art present the familiar in a new light?

A four-year collaborative project by Clare Arni and Pushpamala N, Native Women of South India: Manners and Customs probed the history of photography as an ethnographic tool and the ‘typology’ of representation of women in popular culture. By recreating well-known and iconic images through photo-performance and also deconstructing them at the same time, it plays with ideas of subject and object, photographer and sitter, as well as the real and the staged. This image recreated in the style of a 19th century ethnographic portrait raises several questions, for instance, about power, privilege, colonialism and racism.

People engage imaginatively with the work and come up with very interesting interpretations, which add further layers of complexity...I think that it is the audience that completes the work of art.

– Pushpamala N

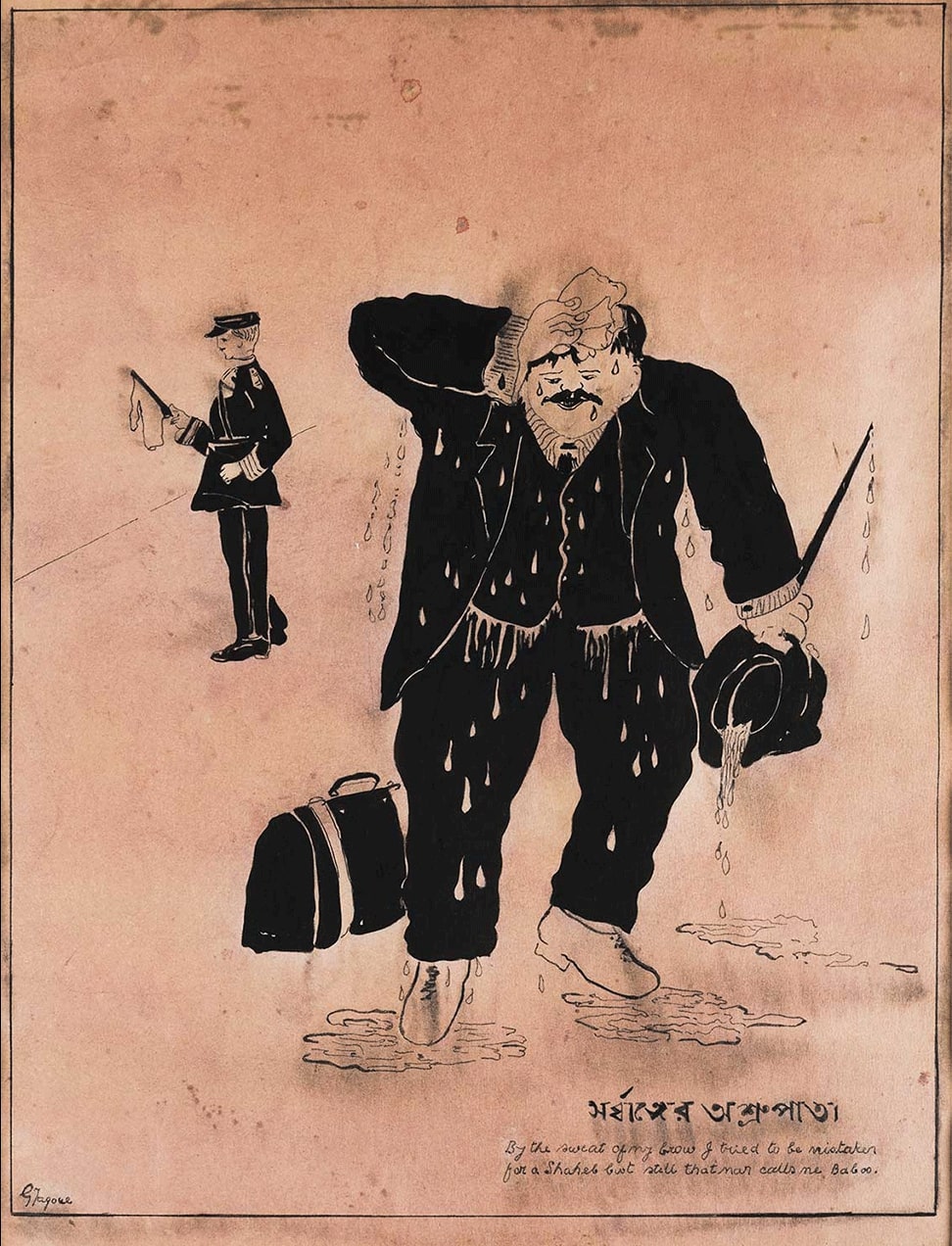

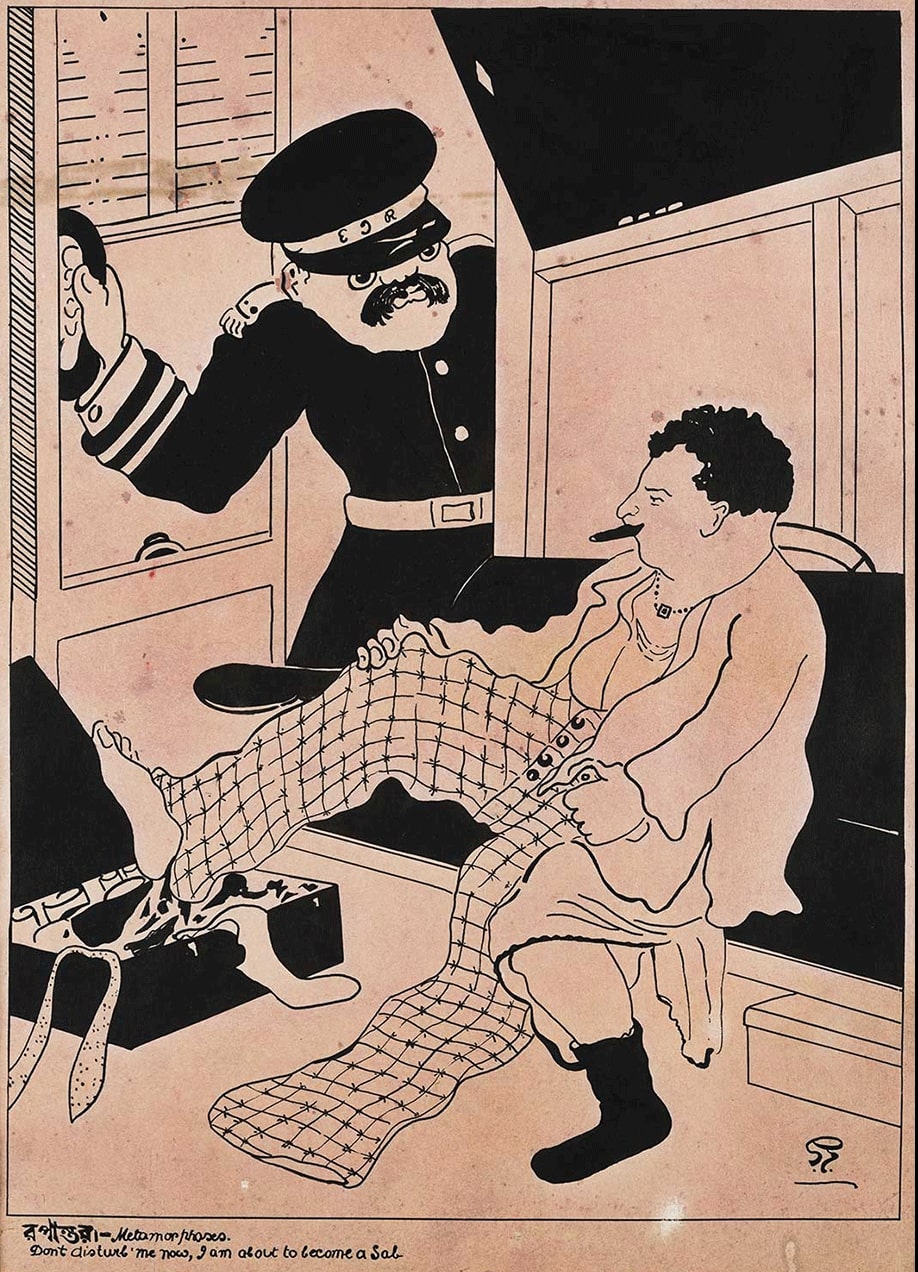

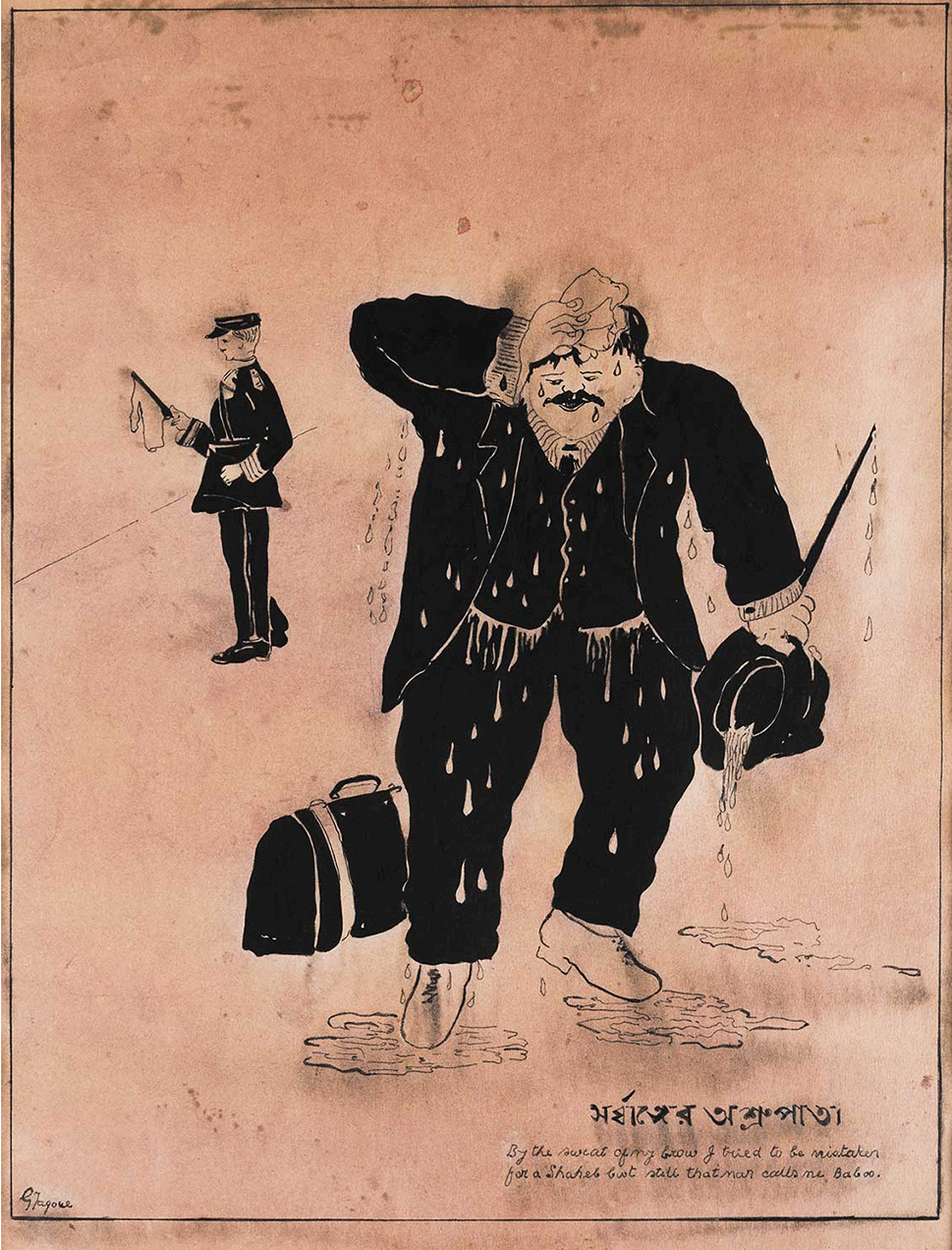

Artists have long used satire and ridicule to highlight social, political and everyday issues. Humour and irony often speak to deeper truths that may not be visible on the surface, distilling them and conveying them to us in ways that are not only easy to understand but also more palatable because we take pleasure in the joke – that's what makes them such powerful tools. A key member of the satirist tradition in the Indian context is modernist artist, Gaganendranath Tagore, whose caricatures form a scathing study of the hypocrisies of Hindu orthodoxy, and the conceits of the Bengali babu and his attempts to ape the European class.

When deformities grow unchecked, but are cherished by blind habit, it becomes the duty of the artist to show that they are ugly and vulgar and therefore abnormal.

– Gaganendranath Tagore

Why should art seek to dismantle the world as we know it?

How can it speak to different and new contexts or challenges?

Is there more than one way to read an image?

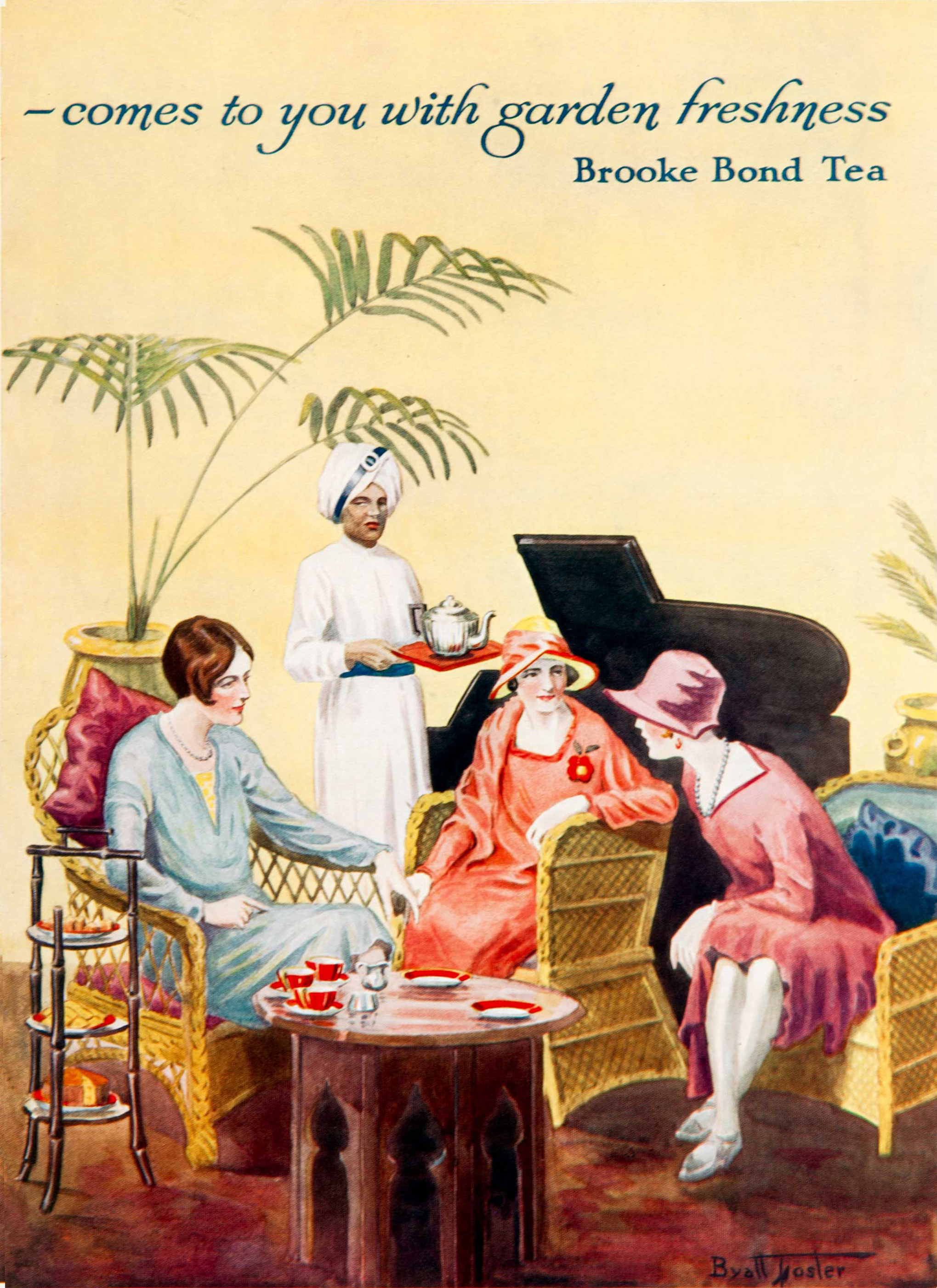

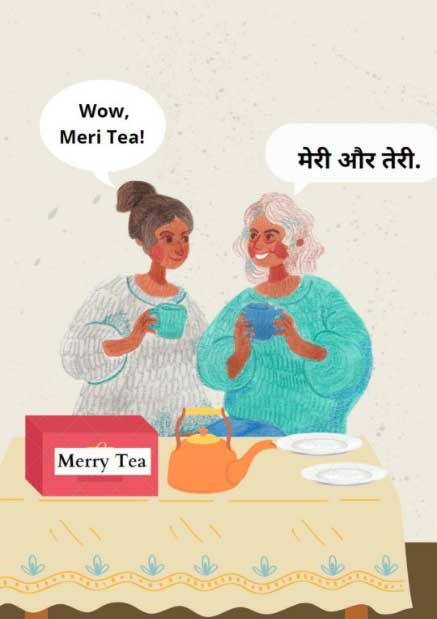

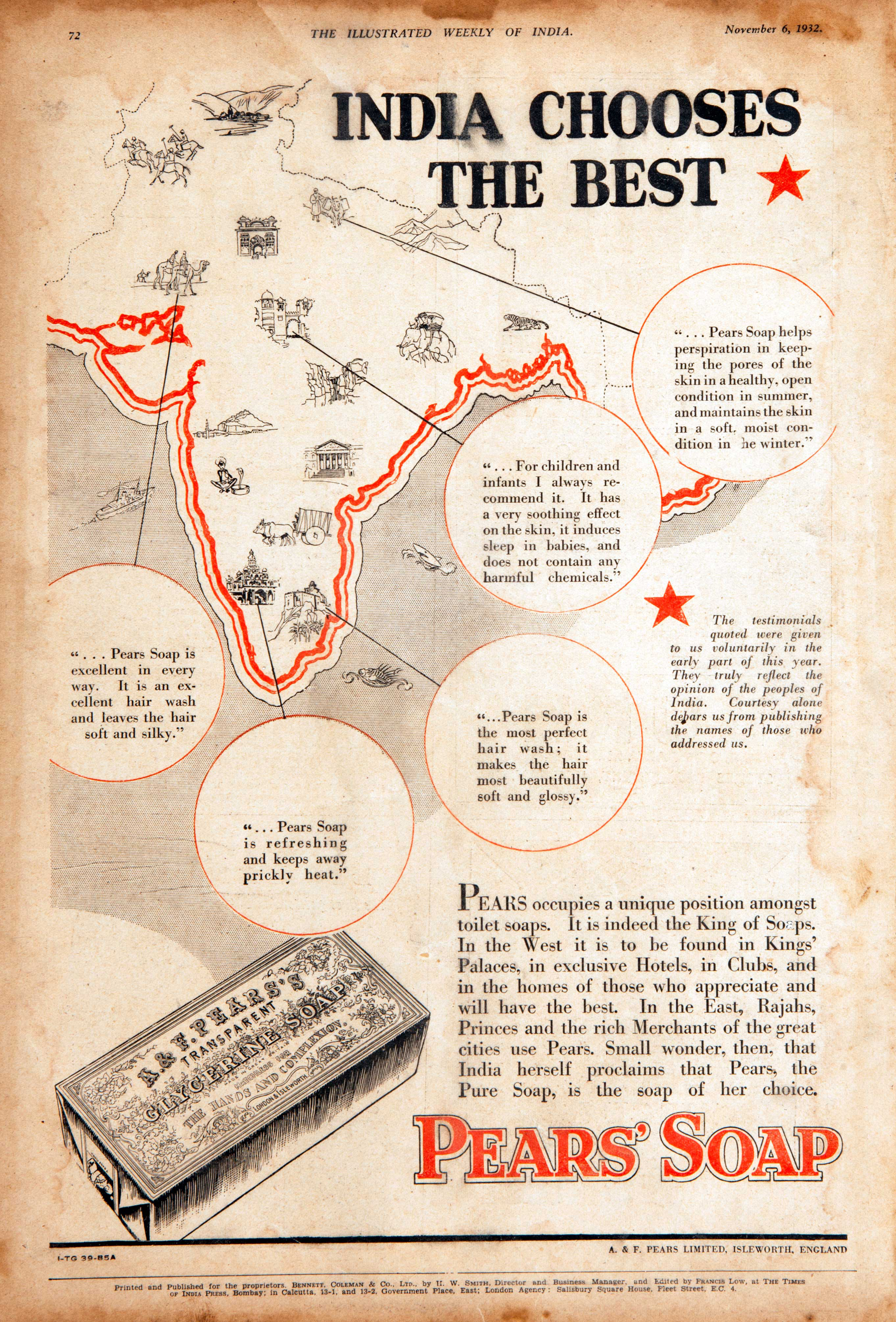

Advertisements play a major role in shaping our society and the ways in which we see, think, understand and act. They mould both our perceptions of ourselves and our aspirations of who we want to be. From earlier popular print forms to today's social media campaigns, they have always had the ability to operate on multiple levels: from the economic and sociopolitical to the ideological and cultural. This makes them potent vehicles to deliver social and political agendas as well as promote other topical and relevant issues; and consequently enables them to exert a remarkable influence on our politics, social values, lifestyles and worldviews.

How does art make us re-examine and reflect upon the world?

What are the histories that it brings to life?

What are the forgotten stories that lie behind its surface?

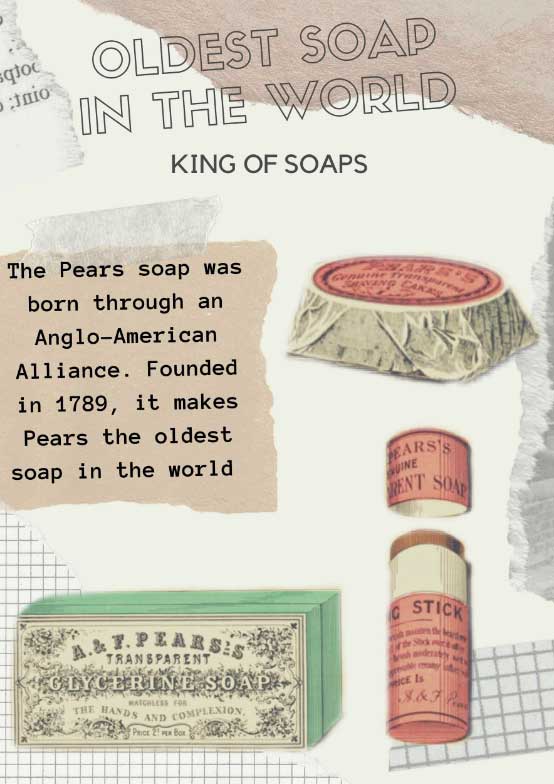

Wright's Coal Tar Soap was a popular brand of domestic soap for over 150 years, and its descendant, Wright’s Traditional Soap, is still available in supermarkets and pharmacies around the world. The original product was created in 1860 by William Valentine Wright from "liquor carbonis detergens," a liquid by-product of the coal distillation process that was turned into an antiseptic soap to cure skin problems.

There is a certain irony to the situation...The picture itself says that it is a “safe soap brand” however, recently the company has been asked to remove its “coal tar” components. [The new] Wright’s Traditional Soap [therefore], does not contain coal tar; instead, tea tree oil has been added for its antibacterial characteristics.