Tie and dye techniques like ikat and bandhani were developed in different parts of the world historically, creating designs which visualised local stories and customs on hand-made cloth. Painted Stitches, Woven Stories takes you on a journey to discover variations of woven textiles in clothing, photographs, paintings and contemporary art.

Curated by

Vaishnavi Kambadur

& Arnika Ahldag

Vaishnavi Kambadur

& Arnika Ahldag

Folding, twisting, pinching, resisting, dipping… What role do tie and dye textiles play in the vast and rich history of textile production around the world? The second iteration of the series Painted Stitches, Woven Stories initiates an interaction between the 19th and 20th century textiles of Central Asia, Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent with contemporary art. It expresses environmental, emotional and sensorial nuances by asking questions like — How do makers tie and dye textiles? What is the link between sunlight, water and dyeing of cloth? Did common people and royalty clothe themselves with the same type of garments? How do patterns and motifs indicate local customs? How did the design of resist dyed textiles affect trade between the Indian subcontinent and other regions of the world? This exhibition seeks to contemplate these questions through text and audio pieces that interpret the textile arts historically and through speculation.

It will take 40 minutes to go through the exhibition with accessibility features that include alt text, transcripts and audio description.

Part 1: Ikat

Single or warp ikat robe which was woven in Uzbekistan in the late 19th or early 20th century. It was lined with a printed cotton fabric which was probably produced in Russia. The trim is made using the loop manipulation technique. Front (left) and back (right).

Uzbek Ikats are called abr, a Persian word that translates to cloud. Abr-bandi or ikat weaving was one of the most significant techniques to be practiced in Central Asia. Ikat woven yardages were used to create dowry clothing. A husband would give his future wife an ikat fabric that she would then convert into a robe. The warp ikat on the robe above is quilted with straight running stitches and yet it doesn’t overpower the visual impact of the ikat.

Weft ikat tubular skirt which was resist-dyed and woven in the early 20th century.

Do the diamond patterns on the ikat above stretch widthwise? Does it mean that weft ikats like these were hugely popular as ceremonial costumes or dress? In this ikat, we see the extent of how tie and dye can change when we switch from tie-dyeing the warp to the weft. Even though Thai courts were known to be one of the keepers of weft ikats, these ikats were also made in smaller back strap looms in homes/islands of the Khmer people. Often, the maker, a woman, would tie the back-strap loom around her waist to maintain balance while she weaves. The woven textile would extend from her waist/lap to the other end of the loom which is looped with a rope or cord tied against a tree, post or a house.

A silk patola sari woven in a vohra-gaji bhat pattern which was made in the 19th century in Gujarat, for the Indian market.

Patan in Gujarat is well known for the finest patola in the world. It was woven in double ikat by Jain weavers or dyers of the Salvi community who migrated from Northern Maharashtra many centuries ago. Threads from warps and weft are organized in bundles and then tie-dyed. Double ikat which dyes both the warp and weft is one of the most complex processes. This knowledge is passed down generationally as weavers teach their families and it can take close to fifteen to twenty years to master the practice. Scholars claim that the double tie-dye process before weaving is a family secret, something that cannot be understood without making the patola several times with precision.

A silk patola ceremonial costume or cloth which was made and traded in the 19th century in Gujarat, for the Indonesian market.

The silk patolu cloth above contains the eight-pointed star pattern woven intricately to fit the narrow width of the cloth. In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, patola and imitation patola were exported to the Indonesian islands. Out of a 1000 textiles that would be exported, most of them would be imitation patola made with printing techniques, and only a handful were woven. Many patola would not survive their journey on the trade route because of the humidity or insect rot thus making them very rare.

A printed and mordant dyed imitation patola which was made and traded in the 19th century in Gujarat, for the Indonesian market.

A ceremonial banner or cloth which was made in Gujarat for the Indonesian market in the 19th or 20th century.

Listen to the curators having a candid conversation about the sound of a loom, the tension of cloth and the many patterns which imitate each other.

Part 2: Bandhani

Bandhani is a textile that closely intertwines with the everyday in India, whether it is a colourful bandhani dupatta hanging out to dry, a woman tucking in the pallu of a bandhani sari or as a much explored DIY technique. In the markets, bandhani fabric is unfurled only when someone buys it, to prove that the fabric is tied and dyed. And thus, the unfurling of the fabric today becomes a marker of originality.

In North-West India, Punjab, Gujarat, Orissa and regions of Southern India, the tie and dye is more evident because the circles or square shapes show us that the threads wrapped before dyeing create impressions that we see as a pattern or a design.

A silk bandhani sari which was made in the late 19th century and worn by a Gujarati or Rajasthani woman.

The function of a tie and dyed cloth changes based on the region of India it is found in. For instance, a bandhani sari from Rajasthan could be different from an odhani worn in Kutch or a turban worn in a court of North India. A single sari can have more than 5000 knots. The pink knots on the sari above are extremely fine, with hundreds of swirling vines and flowers which are connected to each other. The edges of the sari are dyed in pink with more bandhani floral and vine patterns.

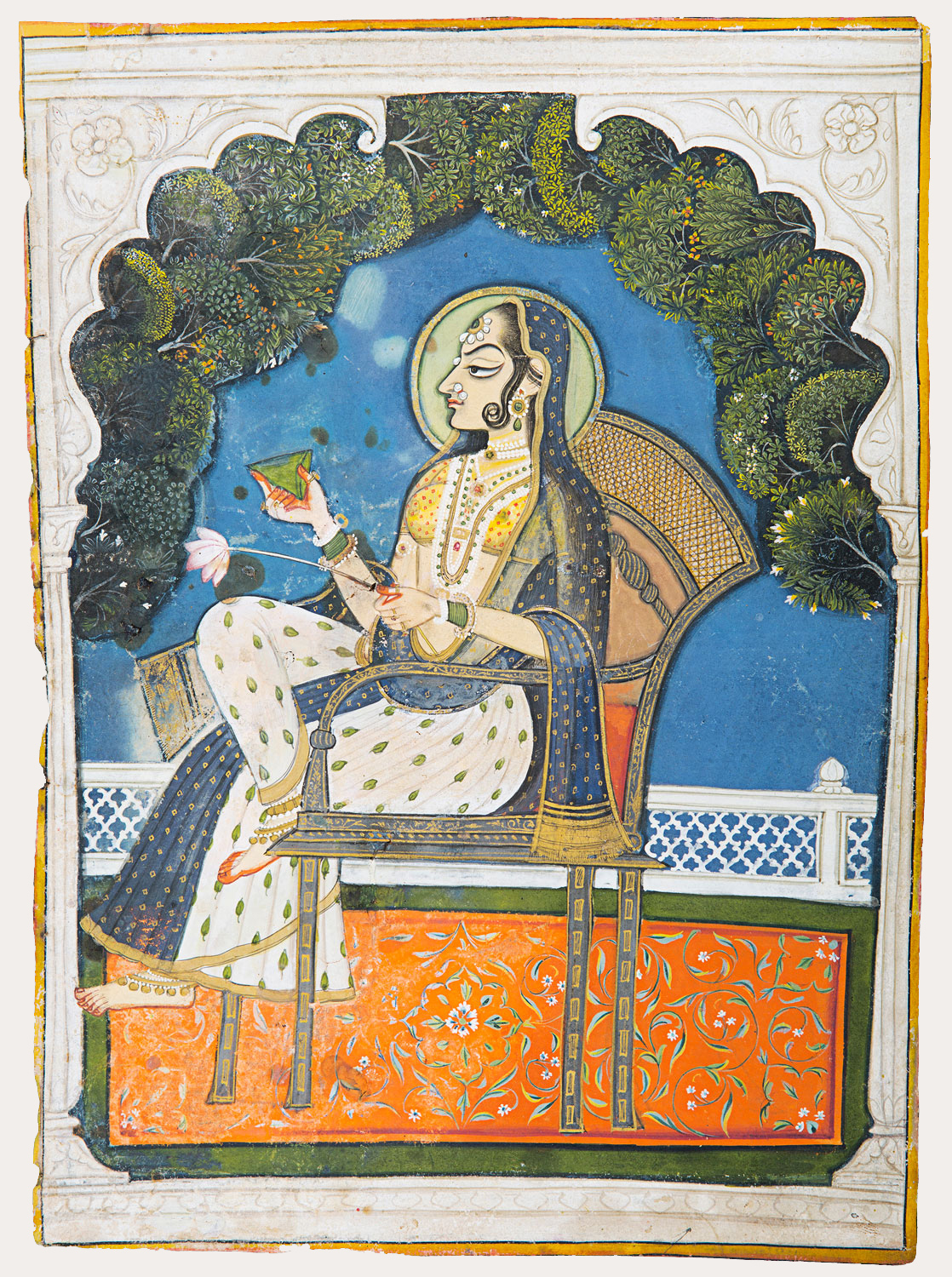

A Kishangarh painting from Rajasthan which was made in the late 18th or early 19th century using opaque watercolour on paper

A bandhani silk odhani which was made in the early 20th century. It has a woven panel running through the center.

What is the significance of wearing these headcovers? Odhanis or Odhanas are headcovers or shawls worn by women and dyed by members of the Khatri, Memons or Sonaras communities of Gujarat. Brides would use them to cover their faces during the wedding ceremony before they would reveal themselves by unveiling the odhani. An odhani tie-dyed in red and green like seen above, with a stitch and gold trim running down the center, became an important aspect of a woman's married life. Many rituals around the veiling or unveiling of an odhani revolved around a woman's gender. If and when she became a widow, she had to give up the odhani which indicated that the keepers of an odhani were almost always married women.

A silk bandhani sari with floral and leaf pattern in the center and a metallic border which was made in the early 20th century in Rajasthan or Gujarat.

The above red bandhani has fine dots which form animated patterns like hopping rabbits, dancing pheasants called kukkat, flying birds called chidiya and sprinting tigers called sinh. If you look closely, do you see human figures that look like “dancing dolls” wearing odhanis with their arms up in the air? Or, are these perhaps shepherds surrounded by animals? Below the figures you can see the elephant, tiger and flower pattern and a pan bel design which resembles the paan leaf climber plant. The bandhani could have been made by folding it into a half so that the motifs form a mirror image of each other. With two leafy tree patterns as pillars, all the animals and dolls look like they are moving towards a flowering lotus.

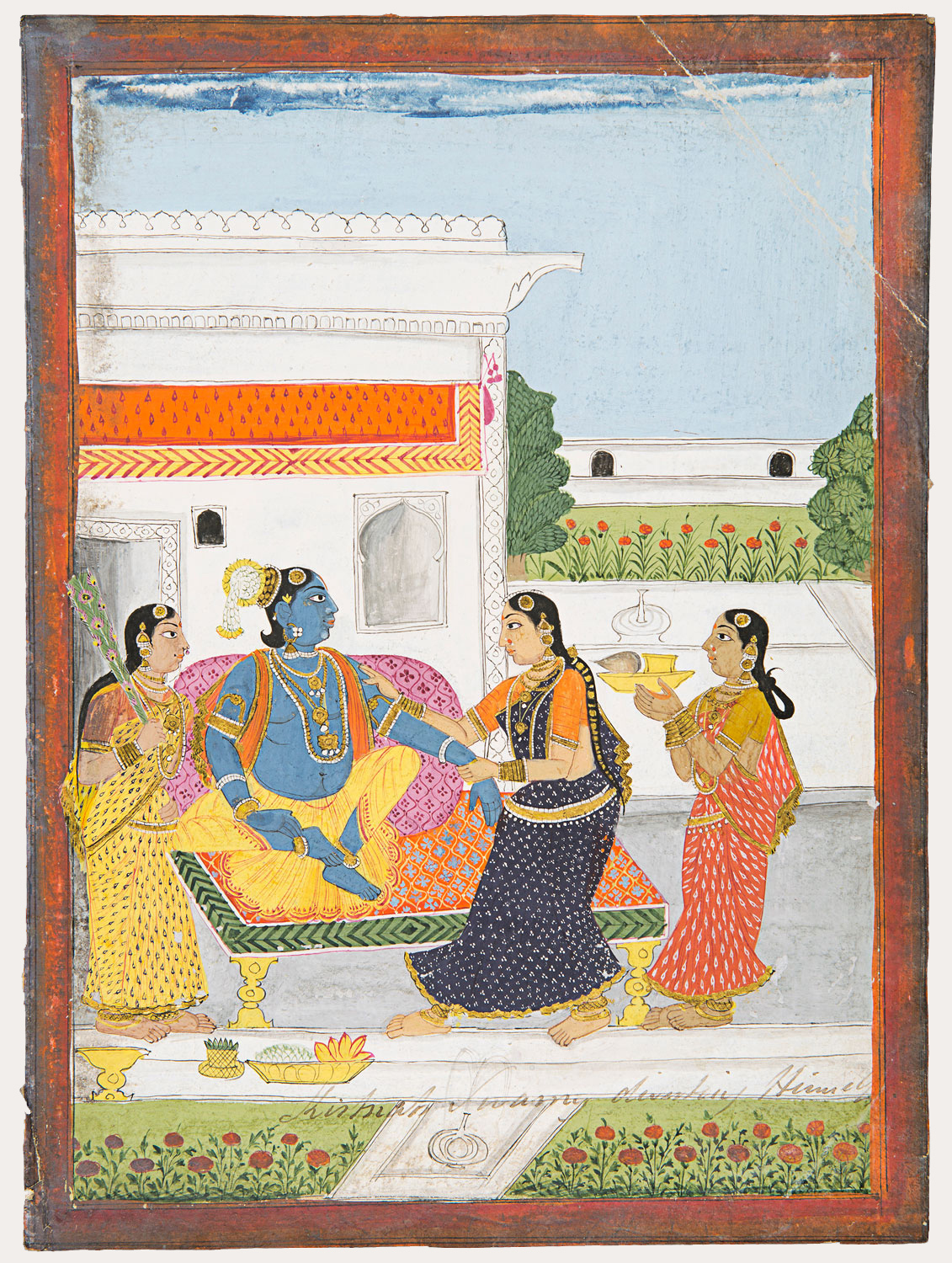

A company painting from the 19th century which was made in South India, possibly Tamil Nadu using watercolor on paper.

In the sixteenth century, Saurashtrian weavers from Western India migrated to Madurai in Tamil Nadu, bringing with them the tie-dye weaving practice of sungudi. The company painting, possibly from Tamil Nadu, depicts three female attendants surrounding Krishna, one of whom is draped in a dark blue sungudi sari and an orange blouse. The white dotted patterns in clusters of three seen on her sari are a common motif and such patterns were perhaps inspired by sights of stars in the sky.

A black and white photograph which was made in the 20th century.

In the photograph, the two women who are dressing the central woman are wearing printed blouses and skirts. The floral print and vertical stripes are more evident on the blouses; however, their skirts have patterns of leheriya that are more prominent. The woman at the back who is looking sideways could be wearing a tie-dyed leheriya. Notice the interruptions and disruptions of pattern. The unpredictability of how the tie-dye will turn out differentiates it from a printed fabric of the same pattern. The black and white contrast of the photograph elevates the textile patterns. The lines that are usually blurred in a tie-dyed leheriya are more prominent in a block printed one.

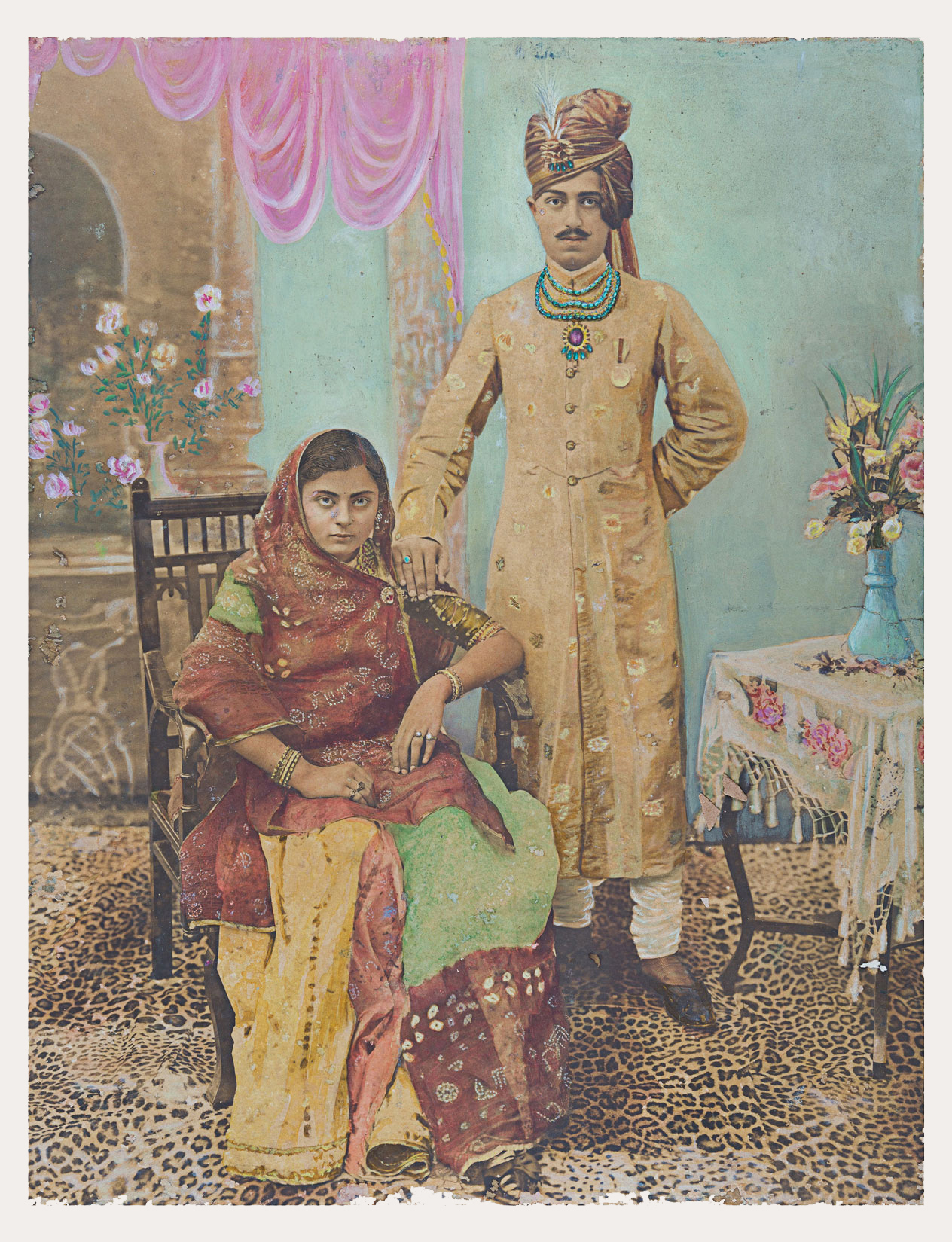

A hand tinted photographic print which was probably made in the early 20th century.

The length of saris and headcovers determine how they are draped around the body. The woman in the above photograph wears a red and green headcover with a different bandhani pattern of finer dots and shapes of squares. This red and green cloth extends to her feet; however, we also see the yellow fabric from a sari or a skirt next to it. Is the green and red cloth a headcover? Is it a half sari? Or is it just a border or pallu of a sari not more than four metres long?

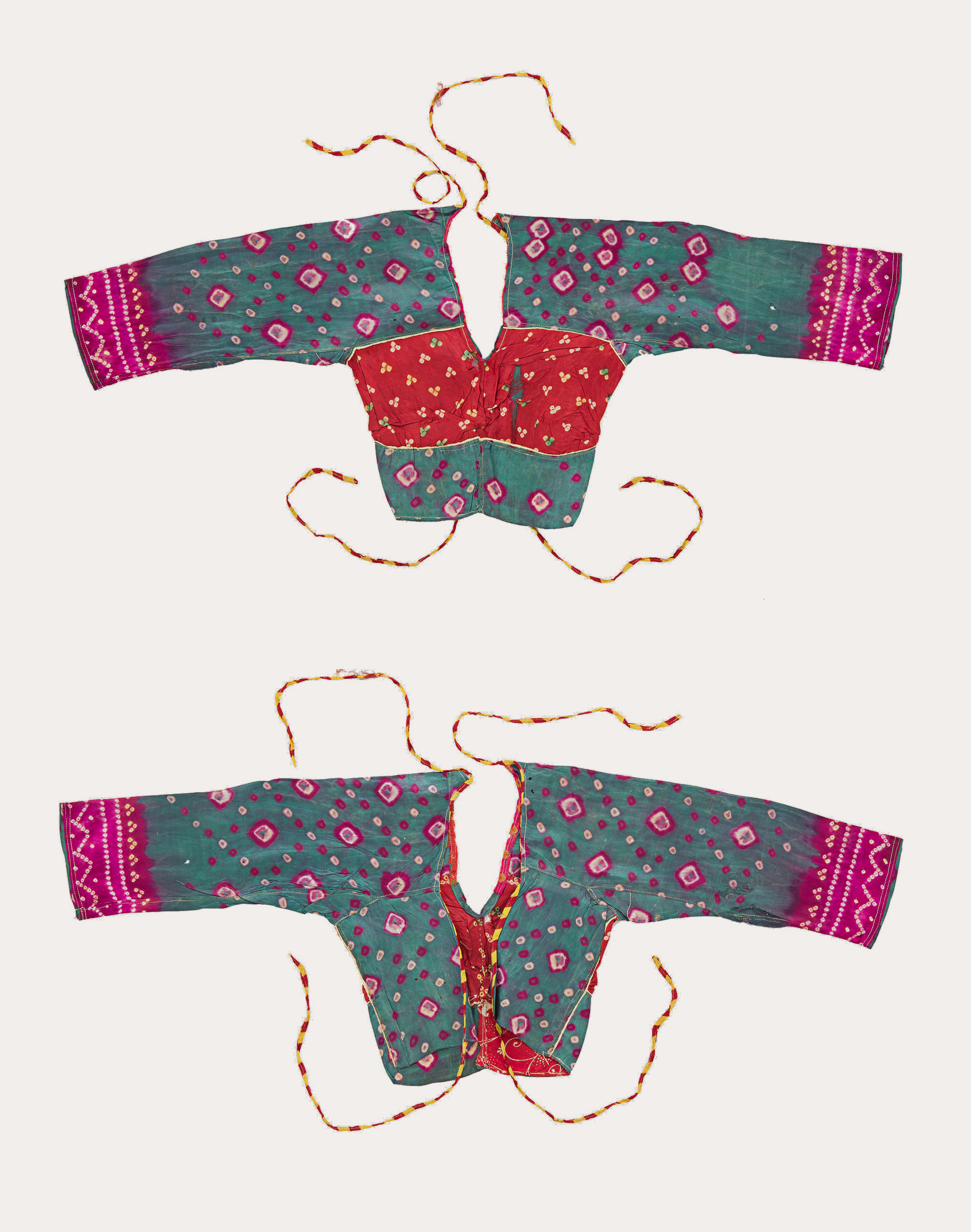

A choli or blouse with bandhani and leheriya details which was made in the 20th century in the North-Western part of India. Gift of Michael & Mary Abbott AO, QC.

The cholis that you see above wouldn't always be visible when a woman wore it. We would see a glimpse of a sleeve as the odhani covers the other sleeve and chest. Notice the pink cuffs on the sleeves which could have been taken from a sari's border? The lining and center of the blouse is a red and yellow bandhani and the adjustable loose strings and tie-cords are made with a leheriya cloth. The blouse is torn at the center and fragile in the corners, which indicates that it was originally made for a particular woman, but then perhaps passed on to a younger woman in the family with a different body type. Women would usually wear a choli with a skirt or a sari and an odhani. Stitched garments, like this blouse, are often made from repurposed old saris, and become a patchwork of formerly worn textiles of the family or community.

A tie-dyed cotton turban cloth for men from Rajasthan which was made in the 2Oth century.

The long cloth was made to be worn as a turban and is also called a pagadi or a safaa depending on the occasion that the cloth was draped around the head. The pink and yellow diagonals with little blue boxes make them either a leheriya or a mothra pattern. As a leheriya pattern, it's possible that this turban was draped by a king as an everyday turban cloth. A covered head was a sign of respect in courts and held a lot of cultural significance. The little blue geometric boxes appear like uncut gemstones.

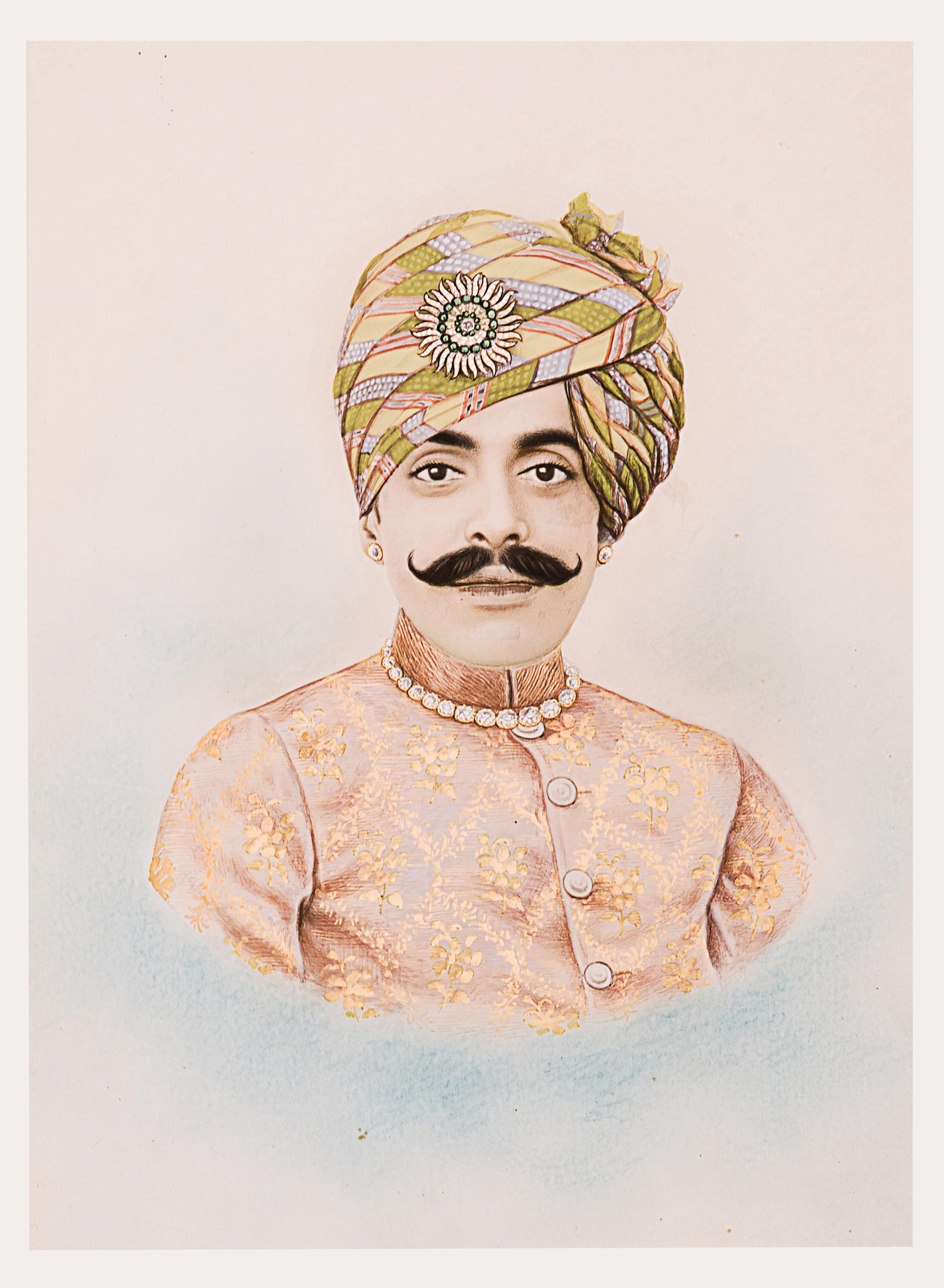

Hand painted photographic print of possibly Maharana Bhupal Singh of Udaipur which was made in the 20th century.

Maharana Bhupal Singh was known for wearing a mewari leheriya as part of his everyday wardrobe. In most of the other painted photographs, we see him wearing a bright pink leheriya but in the portrait above, the artist has depicted him in subtle colours of blue, yellow and green. The boxes or squares within the leheriya indicate its resemblance to the turban cloth above.

A tie-dyed leheriya pagadi or safaa which was made in the 20th century possibly in the form of a mothra design pattern.

At first glance, the leheriya turban looks like a woven check pattern. The bright pink fabric extends a few inches to waves in yellow and green before the waves begin to overlap. Some rare leheriyas were tie-dyed in two different directions forming parallel waves, like, in this leheriya where the pink waves or lehrein intersect and form small boxes.

Listen to the curators speculate about the environment’s role in changing the design and hidden symbolism of patterns.

Raisa Kabir

নীল. Nil. Nargis. Blue. Bring in the tide with your moon...

2019, HD Video, 12 minutes 49 seconds

নীল. Nil. Nargis. Blue. Bring in the Tide With Your Moon is a video work based on Raisa Kabir's performance with the same title in which she dyes linen and jute with indigo on the Scottish coast, where British nuclear submarine warheads are kept underwater, and then weaves it on a backstrap loom in the sea. Indigo and jute, both produced in Bengal in Scottish owned factories, added to the violent history of displacement and colonial struggle. Raisa's work examines the heritage of trauma, the embodied pain of textile production, and the lost histories of textiles as they crossed the seas between India and the UK.